|

Copyright, Attention: This website and its contents contain intellectual property copyright materials and works belonging to the National First Ladies’ Library and Historic Site and to other third parties. Please do not plagiarize. If you use a direct quote from our website please cite your reference and provide a link back to the source.

First Lady Biography: Martha Washington

MARTHA DANDRIDGE CUSTIS WASHINGTON

Born:

Chestnut Grove Plantation, New Kent County, Virginia

1731, June 2.

Father:

John Dandridge (1701-1756), emigrated from England to Virginiain 1715 with older brother William. A planter, in 1730, he served as clerk of New Kent County.

Mother:

Frances Jones (1710-1785), born in York County, Virginia, married John Dandridge in 1730.

Ancestry:

English, Welsh, French; Martha Washington's father John Dandridge was an English immigrant. Her maternal great-grandfather Rowland Jones (died, 1688) immigrated from Oxfordshire, England to Virginia. Tradition identifies the Jones family as originating from Wales, with a Macon family that married into the Joneses being French Huguenots.

Birth Order and Siblings:

Eldest child; three brothers and five sisters, John Dandridge (1733-1749), William Dandridge (1734-1776), Bartholomew Dandridge (1737-1785), Anna Maria "Fanny" Dandridge Bassett (1739-1777), Frances Dandridge (1744-1757), Elizabeth Dandridge Aylett Henley (1749-1800), Mary Dandridge (1756-1763); allegedly her younger illegitimate half-sister (date of birth unrecorded) was a slave; Ann Dandridge Costin, was said to be one-quarter African, one-quarter Cherokee Indian and half-white; there is further evidence of an illegitimate half-brother Ralph Dandridge (date of birth unrecorded), who was probably all white.

Physical Appearance:

No extant record but tradition identifies as being less than five feet tall; dark brown hair

Religious Affiliation:

Church of England

Education:

Informal education; trained at home in music, sewing, household management. Later knowledge of plantation management, crop sales, homeopathic medicine, animal husbandry suggests a wider education than previously thought. Probably taught by indentured Dandridge family servant Thomas Leonard, and regularly tutored for about five years until the age of 12 or 13 at Poplar Grove Plantation, the home of a friend of the Chamberlayne family.

Occupation before Marriage:

No documentation suggesting to the contrary, it has been assumed that Martha Washington's youth was spent much as others of her class and gender were, preparing for management of a plantation, learning various needlework arts, playing a musical instrument and perhaps singing and dancing.

Marriage: Marriage:

First marriage:

19 years old, married 1750 to Daniel Parke Custis (1711–1757), manager of New Kent County plantation of his father Councilor John Custis of Williamsburg. They lived at a mansion called "White House," on the Pumunkey River. Nineteen years old when she married a man who was twenty years her senior, and then 26 when she was widowed with two children, Martha Custis had considerable power through her wealth and privileged social status.

Evidence of her business acumen in the lucrative tobacco trade is found in letters she wrote to the London merchants who handled the exporting of the large Custis crop output. It has been asserted by many of George Washington's biographers that these factors made her potential as a wife an attractive and important factor in his courting of her.

Second:

27 years old, married 1759, January 6 at "White House," to Colonel George Washington (1732–1799) commander of the First Virginia Regiment in the French and Indian War, former member, House of Burgess, Frederick County (1758). Although there is no known “pre-nuptial” as modern times would equate it, the great inheritance which would come to Washington as a result of his successful courtship of Martha Custis is widely believed to have been a factor in his interest in marrying her.

They lived at estate "Mount Vernon," initially leased from his half-brother Lawrence's widow, and inherited upon her 1761 death.

Children:

By first marriage:

Daniel Parke Custis (1751–1754), Frances Parke Custis (1753–1757), John Parke "Jacky" Custis (1754–1781), Martha Parke "Patsy" Custis (1756–1773)

By second marriage:

None

Raised:

Grandchildren George Washington "Wash" or "Tub" Parke Custis (1781-1857), Eleanor "Nelly" Parke Custis (1779-1852)

Occupation after Marriage:

With her extremely large inheritance of land from the Custis estate and the vast farming enterprise at Mount Vernon, Martha Washington spent considerable time directing the large staff of slaves and servants. While George Washington oversaw all financial transactions related to the plantation, Martha Washington was responsible for the not insubstantial process of harvesting, preparing, and preserving herbs, vegetables, fruits, meats, and dairy for medicines, household products and foods needed for those who lived at Mount Vernon, relatives, slaves and servants - as well as long-staying visitors.

During the American Revolution, Martha Washington assumed a prominent role as caretaker for her husband, appointed the General of the American Army by the Continental Congress, and his troops (winter 1775, Cambridge, Massachusetts; spring 1776, New York; spring 1777, Morristown, New Jersey; winter 1778, Valley Forge, Pennsylvania). She lent her name to support a formal effort to enlist women of the colonies to volunteer on behalf of the Continental Army. It involved her writing to the wives of all the colonial governors and asking them to encourage the women of their colonies to make not only financial contributions but to sew and gather necessary supplies for the Continental Army.

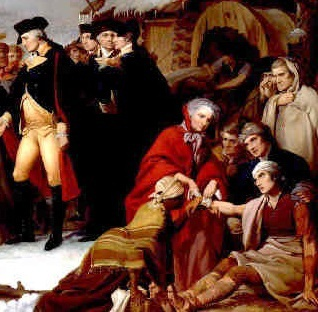

During the famously bitter winter spent at Valley Forge, Martha Washington permanently endeared herself to the soldiers. Often starving for want of food, their feet freezing in the snow and their outer garments too thin to withstand the cold, she made the rounds of visiting them, providing as much food as she could have donated, sewing socks and other outer garments and prevailing on local women to also do so, she also nursed those who were ill or dying. Her commitment to the welfare of the American Revolutionary War veterans would remain lifelong. In appreciation, American servicemen addressed her as "Lady Washington."

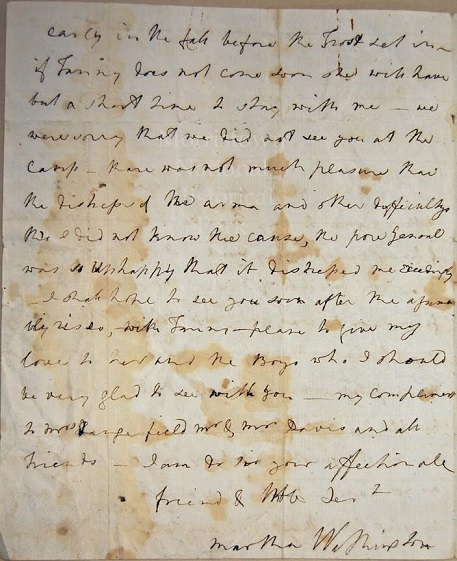

Only supposition can be made about the true nature of her relationship with George Washington since she burned as much as she could find of the correspondence she had which had been exchanged between them, just prior to her death. There is the suggestion of a cordial and affectionate marriage, but not one of great passion.

Presidential Campaign and Inauguration:

Since George Washington was unanimously named President, there was no election campaign. Unable to attend his April 30, 1789 inaugural ceremony in the first capital city of New York, Martha Washington followed the route traveled by him a month earlier. She was honored as "Lady Washington," a public figure in her own right in ceremony and procession by local citizen groups, all of which was reported in the national newspapers.

She was present for his second inaugural on March 4, 1793 in Philadelphia but took no public role in the ceremonies.

First Lady:

1789, April 30 - 1797, March 4

57 years old

Martha Washington's eight years as the first First Lady were extremely unpleasant to her personally, but she viewed it as duty to her husband and her country. By the time she arrived at the capital, her husband's secretary, who had lived in Europe, created a series of rigid protocol rules that she found especially limiting of her, particularly the one which forbade her and the President from accepting invitations to dine in private homes. Despite the company of her two grandchildren, she expressed a sense of loneliness in New York, the first capital, where she had fewer personal friends than she would find in the next capital of Philadelphia (1790-1800). She also discovered that even her mundane activities like shopping or taking her grandchildren to the circus, which were recorded by the press.

Establishing her public role as hostess in the series of presidential mansions ( two in New York and one in Philadelphia ) Martha Washington held formal dinners on Thursdays and public receptions on Fridays.

. .

No evidence suggests what or if she sought to influence any of the President's decisions; later remarks attributed to her imply her to be a strong partisan of his Federalist Party. Newspapers of the Anti-Federalist Party criticized the formality of her receptions as evoking the royal court of the British monarchy, against the tyranny of which the American Revolution had been fought.

She remained beloved by Revolutionary War veterans, and was publicly known to provide financial support or to intercede on behalf of those among them in need. Not only Americans, but Europeans responded to Martha Washington as something of an American heroine, sometimes sending her lavish gifts. One British engraver even sought to capture her image and sell it to the mass public, creating a picture that looked nothing like her but was labeled " Lady Washington."

There is evidence of great mutual care and affection between the first president and his wife. She was conscientious about ensuring in every way she could the dignity of him as a symbol and that his reputation was never compromised. She also recognized the differentiation necessary between her own personal life and the way she was perceived by the public.

After he underwent the surgical removal of a possibly cancerous growth on his left leg in 1789. Martha Washington made arrangements to mitigate the pain of his painful post-surgical recovery, ensuring that the public streets near their home were cordoned off and straw was laid nearby to muffle sounds.

Post-Presidential Life:

Martha Washington was relieved when her husband's Administration ended and they retired to Mount Vernon. Nevertheless, her life after the presidency was not the idyllic private existence she had anticipated. Rather, hundreds of American citizens as well as visiting foreign dignitaries, such as France’s Marquis de Lafayette, came to visit the former President at Mount Vernon. All expected to be entertained, some even expected to be put up as overnight guests. The former First Lady was not known to have accompanied the former President across the Potomac River to the new federal city being built, even after it began functioning as the official U.S. capital city in 1800. The extent of her travel from Mount Vernon was only to the local city of Alexandria,Virginia.

Upon his death on December 14, 1799, the slaves owned by the Washingtons were promised their freedom upon Martha Washington's death. Making clear the tremendous personal sacrifice that the federal government asked of her in requesting that she permit the remains of the first president to be eventually interned at the U.S. Capitol Building, she wrote to President John Adams that she would acquiesce with her sense of public duty.

As a widow, she welcomed visits from President John Adams and her old friend Abigail Adams, whom she befriended when the latter was serving as the Vice President’s wife. She also courteously welcomed the formal calls from future Presidents and their wives, John Quincy Adams and Louisa Adams, and James Madison and Dolley Madison. One account does quote her as making a disparaging remark about Anti-Federalists, particularly aimed at Thomas Jefferson, whom many Federalists considered to have betrayed the friendship of George Washington.

Although she curtailed her life to Mount Vernon, once the new capital city was established in what was first called, "The Federal City," and then named for her late husband, Martha Washington welcomed political figures who came to pay their respects to her and visit what was then thought to be the temporary burial place of the late president. She expressed her loneliness for her late husband frequently and her desire to soon join him in death. Despite her own self-identity as an entirely private person, her death was considered a matter of national interest and her obituary was widely printed in regional newspapers.

Death:

Her home, Mount Vernon, Virginia

1802, May 22

70 years old

Burial:

Burial vault, Mt. Vernon, Virginia

*Martha Washington was the first presidential widow to receive the free postage "franking" privilege from Congress when she was overwhelmed with the cost of responding to the large number of condolence letters she received upon the death of her husband.

As the first First Lady, Martha Washington was forever iconized in all forms of commemoration alongside the image of her husband. For many generations, framed pictures of both George and Martha Washington were hung in American classrooms, Martha Washington’s patience, steadiness, optimism and loyalty held up as ideal virtues. Among the numerous engravings and illustrations made to commemorate the life of George Washington, his wife was also almost always depicted alongside him. She was also the first historical woman figure to be depicted by the federal government on postage stamps and currency.

|