|

Copyright, Attention: This website and its contents contain intellectual property copyright materials and works belonging to the National First Ladies’ Library and Historic Site and to other third parties. Please do not plagiarize. If you use a direct quote from our website please cite your reference and provide a link back to the source.

First Lady Biography: Julia Tyler

JULIA GARDINER TYLER

Birth:

4 May 1820

Gardiner’s Island, Long Island, New York

*Family records are not certain regarding the exact day of her birth in 1820. Some indicate it was July 23, and not May 4.

Father:

David Gardiner, born, 1784, East Hampton, Long Island, New York; lawyer, real estate property management, state senator; died 28 February 1844 as a result of the explosion of the naval cannon “The Peacemaker,” during a Potomac River excursion of the naval cutter Princeton.

A graduate of Yale University in 1804, he counted the future U.S. Senator ofSouth Carolina, John Calhoun among his classmates. He practiced law in New York City from 180 to 1815. After his marriage, he dropped law as a profession to manage his wife’s large real estate holdings. He was given management and temporary occupancy of Gardiner’s Island from 1816 to 1822 and the first three of his four children were thus born on the island. He was elected to the New York State Senate in 1824, representing New York’s first district of Suffolk County. He was re-elected to four consecutive one-year terms, serving until 1828. He was a supporter of John Quincy Adams, member of a political party then in transition but which opposed the emerging Democratic Party as led by Andrew Jackson.

David Gardiner was the descendant of English immigrant Lion Gardiner (1599-1683), who purchased his own island off the tip of Long Island from the Montauk Indian tribe, in May of 1639, shortly thereafter supplemented by deed from King Charles I. Gardiners Island has remained in the same family and is the largest privately owned island in the United States. Among the family lore with which Julia Tyler was inculcated was the tale of famous Captain Kidd dropping anchor and burying gold treasure on the island, in 1699. It was also invaded during the American Revolution and War of 1812. The family owned and used African-American slaves to work the property until New York State outlawed slave ownership in 1816. David Gardiner’s paternal line did not inherit the island, however, and he was not born there but rather in nearby East Hampton. David Gardiner was the descendant of English immigrant Lion Gardiner (1599-1683), who purchased his own island off the tip of Long Island from the Montauk Indian tribe, in May of 1639, shortly thereafter supplemented by deed from King Charles I. Gardiners Island has remained in the same family and is the largest privately owned island in the United States. Among the family lore with which Julia Tyler was inculcated was the tale of famous Captain Kidd dropping anchor and burying gold treasure on the island, in 1699. It was also invaded during the American Revolution and War of 1812. The family owned and used African-American slaves to work the property until New York State outlawed slave ownership in 1816. David Gardiner’s paternal line did not inherit the island, however, and he was not born there but rather in nearby East Hampton.

Mother:

Juliana McLachlan Gardiner, born 8 February 1799, New York, New York; married to David Gardiner, 1815, New York, New York; died 4 October 1864, Staten Island, New York

Juliana Gardiner was the daughter of Michael McLachlan, who was born and raised in Jamaica, West Indies. His father had been a Scottish warrior in the 1746 Battle of Culloden, between the Jacobites and the military forces in the service of King George III of England, and was beheaded. It is not known when Julia Tyler’s grandfather moved from Jamaica to New York. It is established that he owned a successful brewery in lower Manhattanand soon diversified into real estate, eventually owning and passing to his daughter some thirteen pieces of valuable Manhattan real estate, both commercial and residential. Her enormous inheritance made Juliana Gardiner one of the wealthiest women in New York at the time.

Birth Order and Siblings:

Third of four children; two brothers, one sister: David Lyon Gardiner (23 May 1816 – 9 May 1892), Alexander Gardiner (3 November 1818 – 21 January 1851); Margaret Gardiner [Beeckman] (21 May 1822 – 1 June 1857)

Ancestry:

English, Dutch, Scottish. Although the definitive origins in England of the Gardiner family remain uncertain, Julia Tyler’s immigrant ancestor Lion Gardiner arrived in Boston on 28 November 1635. With him came his new wife, Mary Wilemson, whose family originated in Woerdon, Holland, they having met when Gardiner worked as an engineer who helped to build fortifications there. It was the same work which brought him to the American colonies, contracted to work for the Connecticut Company.

Julia Tyler’s paternal grandmother Rachel Schellingerwas of Dutch parentage. Her maternal grandfather, Michael McLachlan, was born on the island of Jamaica, to a widowed mother who had immigrated there from Scotland.

Physical Appearance:

Five feet, three inches; brown hair, gray eyes.

Religious Affiliation:

Presbyterian

Education:

Madame N.D. Chagaray Institute for Young Ladies (April 1835 December 1837, also likely January – December 1848), New York City: A finishing school for the daughters of elite New York families, with a curriculum of music, French literature, ancient history, arithmetic, and composition. Julia Gardiner was one of forty boarding school students. What earlier education she received is unknown, though it is likely she was privately tutored at her family home in East Hampton, New York. During her first month as a student in New York, she marked her social debut on 21 May 1835.

Life Before Marriage

After her formal education ended, Julia Gardiner returned to her family home in East Hampton, where she learned to sing and play the guitar, which would prove to be lifelong interests.

Although the circumstances are unknown, sometime in 1839 she secretly arranged to pose for an engraving which was used for a mass-produced lithograph advertisement for the dry-goods and clothing emporium Bogert & Mecamly, on lower Ninth Avenue in New York City. It depicted her strolling in front of the store, carrying a handbag with the words, “I’ll purchase at Bogert and Mecamly’s, No. 86 Ninth Avenue. Their Goods are Beautiful and Astonishingly Cheap.” Although her name was not used, the picture of a rose was printed in the context of “the rose of Long Island.” It was the first known commercial endorsement of a prominent woman in the history of New York. Although the circumstances are unknown, sometime in 1839 she secretly arranged to pose for an engraving which was used for a mass-produced lithograph advertisement for the dry-goods and clothing emporium Bogert & Mecamly, on lower Ninth Avenue in New York City. It depicted her strolling in front of the store, carrying a handbag with the words, “I’ll purchase at Bogert and Mecamly’s, No. 86 Ninth Avenue. Their Goods are Beautiful and Astonishingly Cheap.” Although her name was not used, the picture of a rose was printed in the context of “the rose of Long Island.” It was the first known commercial endorsement of a prominent woman in the history of New York.

A young, unmarried woman’s public exposure, especially in a commercial venture, was considered humiliating within the mores of her parents’ socially elite class and in reaction they took Julia and her sister Margaret first to Washington, D.C. on 9 August 1840 where they were received at the White House by President Van Buren.

Shortly thereafter, they were taken away from the United States for a grand tour of Europe. Arriving from New York in London on 29 October 1840, they visited England, France, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Holland, Belgium, Ireland and Scotland. Julia Gardiner was presented to the Roman Catholic Pope Leo, and kissed his ring in the traditional ceremony and also explored the volcano at Mount Vesuvius. She also carried on brief romances with a German baron and a Belgian count. Through her father’s connection to the Attorney General, the Gardiners were given letters of introduction to the American Ambassador to France, Lewis Cass. Cass arranged for their presentation at the royal court of Louis Philippe on 7 January 1841. It has also been speculated that while in Europe, she likely read of the receiving system established by the then-incumbent First Lady Angelica Van Buren who created a tableau of young women grouped together around the principal woman figure. In Europe, she also witnessed the more formal receiving system where guests’ names were announced and then led into a formal drawing room where the female monarch or consort remained seated and nodded in acknowledgement, surrounded by a court of young women. The family arrived back in the United States at the end of September 1841.

From January to the end of February 1842, Julia and the Gardiner family lived in Washington for the social season. In one letter, the future First Lady recorded that a married then-Congressman quite openly flirted with her: he proved to be the future president Millard Fillmore. She also took in House and Senate debates in the U.S. Capitol Building. On 20 January 1842, Julia Gardiner and her parents were welcomed as guests in the White House by President John Tyler and his two official hostesses, his daughter Letitia Tyler Semple and, daughter-in-law Priscilla Cooper Tyler. The President’s wife, paralyzed by a stroke several years earlier, was unable to fill the role and would die in the mansion that September.

The Gardiners returned to Washington for the winter 1842-1843 social season. Through rapidly-developing friendships with the President’s two eldest sons, Robert and John, the Gardiners became part of the presidential family’s intimate circle. Although it was only a matter of five months since President Tyler had been widowed by his wife of nearly thirty years, his affectionate attention to Julia Gardiner was overt. He proposed marriage to her on 22 February 1843, at a White House masquerade Washington’s Birthday Ball. She refused to accept, and would continue to do so. They soon began a romantic correspondence and appeared together publicly, prompting open public speculation about the relationship. One rumor claimed that Julia would only marry Tyler if he promised to run for election in 1844 and that he would do so only if she campaigned for him among the Northern elite families. However, the fact that the Gardiners were planning an extensive visit to Europe again in the spring and summer of 1844 suggests that marriage was not a foregone conclusion. The Gardiners returned to Washington for the winter 1842-1843 social season. Through rapidly-developing friendships with the President’s two eldest sons, Robert and John, the Gardiners became part of the presidential family’s intimate circle. Although it was only a matter of five months since President Tyler had been widowed by his wife of nearly thirty years, his affectionate attention to Julia Gardiner was overt. He proposed marriage to her on 22 February 1843, at a White House masquerade Washington’s Birthday Ball. She refused to accept, and would continue to do so. They soon began a romantic correspondence and appeared together publicly, prompting open public speculation about the relationship. One rumor claimed that Julia would only marry Tyler if he promised to run for election in 1844 and that he would do so only if she campaigned for him among the Northern elite families. However, the fact that the Gardiners were planning an extensive visit to Europe again in the spring and summer of 1844 suggests that marriage was not a foregone conclusion.

Julia Gardiner, her sister and father returned for a third consecutive winter social season inWashington on 22 February, 1844. In just six days, came the life-changing tragedy which would prompt a Tyler-Gardiner union. Julia Gardiner, her father, President Tyler and members of his Cabinet, as well as social figures like the former First Lady Dolley Madison were making a 28 February 1844 cruise on the naval cutter Princeton when the vessel’s naval cannon “The Peacemaker” exploded. Among others, it killed the Navy Secretary and Secretaries of State and the Navy, and David Gardiner. They laid in state in the White House and were given funerals in the Capitol on 2 March 1844. The Gardiners returned with their father’s remains for burial in East Hampton, New York. Julia Gardiner, her sister and father returned for a third consecutive winter social season inWashington on 22 February, 1844. In just six days, came the life-changing tragedy which would prompt a Tyler-Gardiner union. Julia Gardiner, her father, President Tyler and members of his Cabinet, as well as social figures like the former First Lady Dolley Madison were making a 28 February 1844 cruise on the naval cutter Princeton when the vessel’s naval cannon “The Peacemaker” exploded. Among others, it killed the Navy Secretary and Secretaries of State and the Navy, and David Gardiner. They laid in state in the White House and were given funerals in the Capitol on 2 March 1844. The Gardiners returned with their father’s remains for burial in East Hampton, New York.

Husband and Marriage:

24 years old, to John Tyler IV (born 29 March 1790, Greenway Plantation, Charles City County, Virginia, died 18 January 1862, Exchange Hotel, Richmond, Virginia) President of the United States, on 26 June 1844 in The Church of the Ascension, New York City. The Gardiner family’s mourning was given as the reason for the “elopement” of the President and Julia Gardiner. There were only twelve guests, including the President’s son John. After the ceremony, there was a wedding breakfast in the Gardiner home, followed by a ferryboat cruise, with various naval salutes in New York Harbor. The couple debarked at Jersey City, where they took a train to Philadelphia. Both there, and in Baltimore, the new presidential bride was the object of enormous public fascination, turning out crowds of thousands to glimpse her. A two-hour White House wedding reception was held on 28 June 1844, with a wedding cake displayed in the Blue Room, and served with wine. The couple then proceeded on 4 July 1844 to “Old Point Comfort,” at the federal Fortress Monroe, near Norfolk,Virginia, where a honeymoon cottage had been outfitted for them. Finally, two days later, they went to the President’s new plantation home “Sherwood Forest,” in Charles City County, Virginia for several days before returning to Old Point Comfort. They returned to Washington in early August.

Children: Children:

Five sons; two daughters: David Gardiner Tyler(12 July 1846 - 5 September 1927);

John Alexander Tyler(7 April 1848 - 1 September 1883);Julia Gardiner Tyler [Spencer](25 December 1849 - 8 May 1871);LachlanTyler(2 December 1851 - 26 January 1902)

Lyon Gardiner Tyler(24 August 1853 -12 February 1935) ;Robert Fitzwalter Tyler(12 March 1856 - 31 December 1927);Pearl Tyler [Ellis](20 June 1860 -30 June 1947)

*Julia Gardiner Tyler is the only woman married to an incumbent President whose children were all born after her tenure as First Lady. Although the second wife of Benjamin Harrison bore him a daughter in his post-presidential years, she had not been married to him during his presidency.

Campaign and Inauguration

Since Julia Tyler became First Lady by marrying an incumbent one-term President, she did not experience her husband’s campaign for and Inauguration as Chief Executive.

First Lady

24 years old

26 June 1844 - 4 March 1845

Although she would prove to be the second youngest presidential wife to serve as First Lady, and the one with the shortest tenure, lasting only eight months, Julia Tyler viewed her status as the spouse of the president to be larger than that of hostess of social events within the mansion, which had been the traditional identity of that role. Part of her willingness to assume a public role might likely have resulted from the influence of former First Lady Dolley Madison who, by this time, was living across Lafayette Square from the White House and was welcomed as part of theTyler family circle. So close did the former First Lady become to the new one that the two of them travelled to New York together in September of 1844.

Julia Tyler is the first known First Lady to have overtly sought newspaper coverage that reported not only of her social events but articles also intended to personally raise and maintain her as a public figure praise. In many respects, she was the first First Lady to seek and earn the status of the modern equivalent of “celebrity,” a woman whose name, face and legend was widely known in her time.

She did this in several specific ways. Most importantly, she befriended the reporter F.W. Thomas, a Washington correspondent for the New York Herald. He dubbed her the grand “Presidentress” in his stories, and went into more glowing details about her clothes, skin and personality rather than the specifics of what transpired at the event. This suggests he may not have been present or else that the articles were ghostwritten; indeed, there is some evidence that the First Lady’s brother Alex Gardiner at least drafted or pre-approved what were essentially press releases under the misleading designation of news. She did this in several specific ways. Most importantly, she befriended the reporter F.W. Thomas, a Washington correspondent for the New York Herald. He dubbed her the grand “Presidentress” in his stories, and went into more glowing details about her clothes, skin and personality rather than the specifics of what transpired at the event. This suggests he may not have been present or else that the articles were ghostwritten; indeed, there is some evidence that the First Lady’s brother Alex Gardiner at least drafted or pre-approved what were essentially press releases under the misleading designation of news.

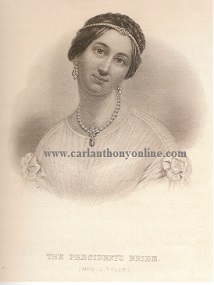

Julia Tyler also sought to have her attractive and youthful facial image widely disseminated. She permitted an engraving to be made of her, based on an oil portrait by Francesco Anelli. It was inscribed with the title, “The President’s Bride” rather than her own name, and mass-produced and commercially sold. She also became the first presidential wife who served as First Lady to have sat for her photograph, posing at the Anthony studios in New York. Julia Tyler’s photograph, however, was not mass-produced and publicly sold (as would those of her successors Abigail Fillmore, Harriet Lane and Mary Lincoln); it was only rediscovered in the Library of Congress collections in 1987, and published for the first time three years later.

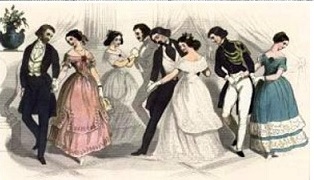

Julia Tyler also gave permission for her name to be used on sheet music used for the popular polka dancing. Called “The Julia Waltzes,” she even sought to have publicized not just the music – but the fact that it had been named in her honor. Although a number of her predecessors had hosted dances for young guests, Julia Tyler is the first known First Lady to have publicly danced during her tenure in the White House. Julia Tyler also gave permission for her name to be used on sheet music used for the popular polka dancing. Called “The Julia Waltzes,” she even sought to have publicized not just the music – but the fact that it had been named in her honor. Although a number of her predecessors had hosted dances for young guests, Julia Tyler is the first known First Lady to have publicly danced during her tenure in the White House.

Finally, that Julia Tyler sought attention as First Lady and believed it to be a public role worthy of national notice, is evident in how she consciously arranged her personal appearance. She drove a regal coach with eight matching white Arabian horses, she dressed in lavish clothing and costumes, and she sought to own an Italian greyhound dog, a relatively-exotic breed in the United States at the time, to accompany her one public promenade throughout the city (the dog was obtained through the U.S. Consul at Naples). All of this was provided not through any public federal funds but the great wealth of her family.

Since President Tyler had no intention of seeking a full term in the 1844 presidential election at the time he married Julia Gardiner, she had knowledge that her time as First Lady would be brief. Thus she accelerated a regular pace of entertaining, afforded the chance to serve as official hostess for only the four months of the last social season of the Tyler Administration, from December 1844 to March 1845. Some among Washington’s social elite also disdained her regal form of receiving guests by seating herself among a dozen young women dressed alike in white and dubbed her “vestal virgins.” From the religious press, she earned disapproval for the abundant supply of champagne she had served to guests and the physical closeness of the new waltz dancing she sponsored and participated in.

The young First Lady also changed public presidential ceremony. She directed that the President be removed from more direct access to the public when he received them. There was a practical reason for Julia Tyler’s changing the format in which a presidential couple received their guests, related directly to the safety and security of the President himself. Previously, the President would simply stand in the middle of the Blue Room to welcome guests and often found himself besieged or even engulfed by guests. During open-house public receptions, this presented both a tiring, somewhat undignified but also dangerous scenario. Julia Tyler’s new configuration had the President standing against the wall, in the deeper side of the oval room. It kept people from coming up behind him and also allowed for the single line of guests to stream in and out efficiently.

Along these lines, Julia Tyler has been anecdotally credited with directing the Marine Band to always play a specific march whenever she and the President entered a public event, later to be famously known as “Hail to the Chief.” It is difficult to find documented evidence of this and the innovation is sometimes credited to her immediate successor Sarah Polk.

While her youth left her relatively ignorant of political machinations than might be the long term spouse of an elected official, Julia Tyler sought to exercise a small degree of influence in the policy realm. With her tremendous fame, she was the recipient of requests from individual citizens for executive clemencies, pardons, military leave and federal employment. She would pass these requests on to the appropriate Cabinet departments or the president himself and indicate whether she supported their plea. Her most successful intercession was helping to commute the death sentence of a notorious New Yorker nicknamed “Babe” accused of piracy on the high seas.

Through the summer, fall and winter of 1844 and 1845, Julia Tyler did serve as the intermediary between the President and her brother Alex Gardiner in his ambitious plan to control all of New York’s Suffolk County appointments and place only pro-Tyler Democrats in those positions. While the strategy was planned by her brother, the First Lady not only transmitted names, open positions and patronage decisions but often indicated her own personal views on potential appointees. When the appointments required Senate confirmation, Julia Tyler assured her brother that she would personally attempt to persuade those who had the power to approve the nominees. It was an effort intended to forge a new party withTyler as leader, and run him as President in 1848.

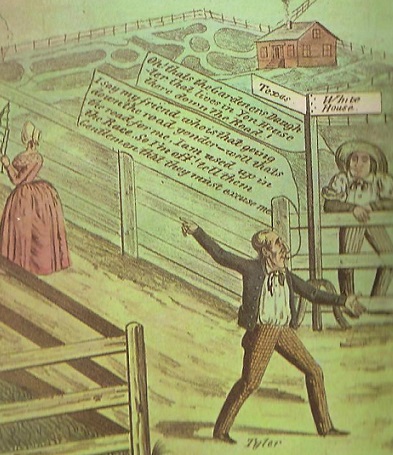

It was the power of her personal charm and a lobbying effort based more on personal flattery and attention rather than policy which saw Julia Tyler strenuously promoting the President’s proposed annexation of Texas among individual House and Senate members. She did this by appearing at the Capitol to listen to the scheduled debates onTexas, and sending out copies of the President’s unique proposal for a joint-resolution annexation, which required a majority of both houses. In one of the first – if not the first – political cartoon that linked a First Lady to a piece of legislation, John Tyler was depicted at a cross-road, one lane marked “Texas,” the other “White House” – meaning a presidential campaign in 1844. Indicating his preference for Texas, Julia Gardiner is shown at the end of the road leading that way, under a parasol as if luring him down it towards glory. A popular ditty began with the words, “Texas was the Captain’s [Tyler’s] bride, ‘til a lovelier one he took…” When Tyler signed the joint-resolution, he further forged the connection between his proudest achievement and his First Lady by awarding her the pen he used. She, in turn, wore it proudly on a chain around her neck at the closing public events of her tenure. On 18 February 1845, she hosted a “Grand Finale Ball,” for three thousand invited guests. Some one thousand candles were said to be burned and ninety-six bottles of champagne consumed, with numerous bands providing continuous dance music.

Occupation After the White House:

Just weeks before his second marriage, John Tyler had assured his eldest and married daughters – Mary Tyler Jones, Elizabeth Tyler Waller, and Letitia Tyler Semple that he had no plans to remarry. While his two eldest sons, John and Robert, accepted Julia (who was younger than the two of them, as well as his first daughter Mary) as a stepmother, as did the two youngest Tyler children by his first marriage, Alice and Tazewell, it took time for the older girls to view her with anything but disdain. In time Mary Jones and Elizabeth Waller did so. Letitia Tyler Semple, however, never did and was often overtly hostile towards Julia Tyler. Feeling a sense of duty to the memory of her mother after whom she was named, Letitia Semple also had served as White House hostess; it was a status she instantly loss with the arrival of Julia Gardiner in the family. Finally, her own marriage was estranged and James Semple never lived as part of the large Tyler clan, although he and Letitia did not divorce. In the post-Civil War years, however, Semple formed a close, even emotional relationship with his step-mother-in-law. This of course earned Julia Gardiner Tyler the permanent enmity of her stepdaughter.

A story that former President John Tyler and his wife were on the verge of divorce and already separated first appeared in the 21 February 1846 New York Morning News and was rapidly picked up in newspapers across the country. The story was true of John Tyler, Jr. and his wife but had been misunderstood to mean the former presidential couple. Nevertheless, the incident turned Julia Tyler forever vigilant about counter-acting any printed untruths about not only herself and her husband, but the policies of his Administration. Insisting on retractions or, at the least, the printing of her side of the story, made Julia Tyler one of the first among First Ladies who learned to integrate published falsehoods about herself and her husband as simply a disturbing element of their lives.

In February of 1853, Julia Tyler again found herself in the national and even international press. England’s Duchess of Sutherland and other prominent women of the British nobility had signed a printed plea to American southern women to do all they could to support the abolition of African-American slavery, a broadside published in American newspapers. Working for over a week on an editorial response in what would prove to be her first and only published writing, Julia Tyler’s “To the Duchess of Sutherland and the Ladies of England” was first published on 28 January 1853 in both the Richmond Enquirer and the New York Herald. It was reprinted in the widely-circulated monthly magazine, Southern Literary Messenger in February. The former First Lady did not attempt to justify slavery but rather to address what she believed were certain truths about the “peculiar institution”: that most slave families were permitted to make the choice of whether they wished to join Christian churches and that selling individual members of slave families was generally avoided by slave-owners. She further mentioned that the population of freed slaves in Virginia was steadily rising and that the American Colonization Society was striving to offer freed slaves a chance to re-patriate to Africa. Her larger point, however, was that England had no right to dictate the policies of another country. She used several points to make this argument: slavery had been introduced in the United States by the British; the Irish, impoverished factory workers in London and merchant and naval seaman class of England lived in what she claimed were more deplorable conditions than did African-American slaves. In truth, despite her northern background, Julia Tyler had been raised to believe there was nothing morally wrong with owning other human beings; in fact, there had been slave labor on her family’s Gardiner’s Island before it was outlawed in New York State. In February of 1853, Julia Tyler again found herself in the national and even international press. England’s Duchess of Sutherland and other prominent women of the British nobility had signed a printed plea to American southern women to do all they could to support the abolition of African-American slavery, a broadside published in American newspapers. Working for over a week on an editorial response in what would prove to be her first and only published writing, Julia Tyler’s “To the Duchess of Sutherland and the Ladies of England” was first published on 28 January 1853 in both the Richmond Enquirer and the New York Herald. It was reprinted in the widely-circulated monthly magazine, Southern Literary Messenger in February. The former First Lady did not attempt to justify slavery but rather to address what she believed were certain truths about the “peculiar institution”: that most slave families were permitted to make the choice of whether they wished to join Christian churches and that selling individual members of slave families was generally avoided by slave-owners. She further mentioned that the population of freed slaves in Virginia was steadily rising and that the American Colonization Society was striving to offer freed slaves a chance to re-patriate to Africa. Her larger point, however, was that England had no right to dictate the policies of another country. She used several points to make this argument: slavery had been introduced in the United States by the British; the Irish, impoverished factory workers in London and merchant and naval seaman class of England lived in what she claimed were more deplorable conditions than did African-American slaves. In truth, despite her northern background, Julia Tyler had been raised to believe there was nothing morally wrong with owning other human beings; in fact, there had been slave labor on her family’s Gardiner’s Island before it was outlawed in New York State.

During her lengthy post-White House years, Julia Tyler continued to travel extensively to the fashionable northern summer colonies of Newport, Rhode Island, Saratoga and East Hampton, New York. Although she met President Zachary Taylor at a reception in Richmond, Virginiain February of 1850, Julia Tyler did not return to Washington, D.C. until February 1861. The incident marking her return to the capital city was the “Peace Conference,” an effort in which her husband participated, a last-ditch effort to avoid civil war. During their stay in Washington, Julia Tyler was called upon by her old friend, incumbent President Buchanan, but was not with her husband to meet president-elect Lincoln. Julia Tyler strenuously defended her husband’s advocating secession and accepting a seat as a member of the Confederate States of America’s provisional Congress. However, he died several days after the Confederate Congress first convened in Richmond. His coffin was covered by the Confederate flag and attended by the Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Despite her sectional loyalty, the widowed ex-president’s wife was able to occasionally obtain a pass that permitted her to travel between North and South lines. She spent part of the war years in Bermuda, with other exiled Confederates, where she contemplated a potential profitable cotton trade scheme. There is also recent suggestion that she was received by Mary Lincoln in the White House, as evidenced by an autographed letter for sale in 2005 from the First Lady to her predecessor.

The end of the war, however, saw her residing in the Staten Island, New York home of her late mother. Following Lincoln’s April 1865 assassination, there was a raid on the house by some locals seeking what they wrongly believed to be Julia Tyler’s Confederate flag.

Ignoring the humiliation that many Confederates felt in the immediate post-war years, Julia Tyler resumed residency in Washington, D.C. in January of 1872. She moved into a rental apartment on Fayette Street in the Georgetown section of Washington, D.C. She made numerous visits back to the White House, under the Andrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant Administrations, receiving considerable publicity during her March 1872 visit to Julia Grant. She donated her portrait to its collection and for display there. Self-titling herself as “Mrs. Ex-President Tyler,” she would go on to help receive guests in a place of honor at receptions hosted by some of her successors including Lucy Hayes and Rose Cleveland, and maintained a correspondence with Lucretia Garfield. In matching the conscious effort she made as First Lady to create a highly visible public profile, as a former First Lady she sought to ensure her place in history by providing biographical information to Laura Holloway, who authored the first comprehensive collective biographies of First Ladies to that time.

Julia Tyler left Washington in the spring of 1876 due to severe financial hardship and returned to Sherwood Forest which had been ordered sold by a court to pay a Bank of Virginia judgment against the Tyler estate – only the unexpected sale of some other property kept it in the family and as the base for Julia where she looked forward to annual summer visits from her children and growing number of grandchildren. By the end of the decade, however, her eldest son David “Gardy” Gardiner was the full-time resident, manager and ultimately owner of the estate.

During a period of financial and emotionally instability, Julia Tyler sought and found refuge in the Catholic Church. She converted to the faith and insisted on a second baptism, which occurred in May of 1872. Her decision proved to be a positive public face of Catholicism to the majority-Protestant American culture. It also led many individual women in the country to write her for advice on how they might find the emotional support which the former First Lady declared that the conversion had provided for her. Mrs. Tyler became somewhat zealous with her wide circle of friends, family and associates in urging them to also make the conversion.

Nevertheless, she made so many frequent return trips to the capital that her public profile there remained high. Trading on an earlier association with William Evarts, the Secretary of State under President Hayes, the former First Lady successfully lobbied to not only gain federal jobs for two of her sons, but to gain for herself the presidential widow’s pension. When Mary Lincoln received it in 1870, Mrs. Tyler believed she would soon rightfully be awarded the same amount of $3000. Her letter-writing and visits to Washington did not prove hopeful for another ten years. In the election year of 1880, however, she was advised by Evarts that even though Congress was now likely to award it based on the support coming from Republicans, the decision could create a backlash against those who still resented granting federal funds to a former Confederate. In 1881 she received $1200 – less than half of what Mrs. Lincoln collected. With Lucretia Garfield becoming widowed upon President Garfield’s assassination later that year, however, all four living presidential widows (Tyler Polk, Lincoln, Garfield) were awarded the same annual amount of $5,000 on 31 March 1882. Mrs. Tyler soon proposed in an anonymously published letter to the Washington Post that the amount should be raised to $10,000. In late 1882, she leased a home in Richmond, Virginia, first in the Church Hill area and then in a house on Grace and Eighth Streets, across the street from her Catholic parish, St. Peter’s Cathedral. She continued to visit one son in Washington, however, in the winter social seasons until 1887.

Death and Burial

69 years old

10 July 1889

Richmond, Virginia

Buried, HollywoodCemetery, Richmond, Virginia

|