|

Copyright, Attention: This website and its contents contain intellectual property copyright materials and works belonging to the National First Ladies’ Library and Historic Site and to other third parties. Please do not plagiarize. If you use a direct quote from our website please cite your reference and provide a link back to the source.

First Lady Biography: Sarah Polk

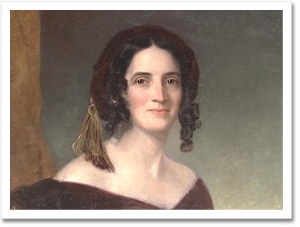

SARAH WHITSETT CHILDRESS POLK

Birth

4 September 1803

Murfreesboro, Tennessee

Ancestry

Scottish, Irish, English; Shortly before her death, Sarah Polk’s friend and biographer, serving as a secretary responded to one of the former First Lady’s maternal cousins about a genealogical matter involving her mother’s ancestors: “Mrs. Polk does not know of any register of her ancestry…She knows nothing of her ancestors in Scotland or Ireland or of any relatives living in those countries at the present time.” Another genealogical site related to Sarah Polk’s paternal ancestors suggests that her American Childress ancestor immigrated from England.

Father

Joel Childress, date and place of birth, 22 March 1777, North Carolina; date and place of death, 19 August 1819, Mufreesboro, Tennessee. Joel Childress ran a large plantation, with cash crops cultivated and harvested by his extensive number of African-American slaves. While it is uncertain how many of the slaves worked on his land, in his will he mentioned four slaves who worked in the home. He was also a merchant, although the nature of what he sold is unclear. He also owned real estate both in the city of Mufreesboro and in the outlaying farm region.

Mother

Elizabeth Whitsett, born 1780, North Carolina; died, 1863, Rutherford County, Tennessee; date of marriage, unknown, place of marriage, Sumner County, Tennessee. In a letter written by Mrs. Polk’s secretary in 1890, she wrote that the former First Lady “has no record of the date of their marriage,” but confirmed that they had married in Campbell County, Virginia; this location is likely in reference to her maternal grandparents, not her parents.Elizabeth Childress’s parents John Whitsett (1743-1819) and Sarah Thompson Whitsett (1746/1747-1831) both lived to a relatively old age. Although they relocated from Tennessee to Alabama, Sarah Polk knew her maternal grandparents well. She was named for her grandmother Sarah Thompson Whitsett.

Siblings

Third of six siblings; Anderson Childress (1799-1827), Susan Childress [Rucker] (1801-1888); Benjamin Whitsett Childress (born and died in infancy, n.d. circa 1803-1807); John Whitsett Childress (1 June 1807 – 6 October 1884), Elizabeth Childress (born and died in infancy, n.d.)

Religion

Presbyterian

Education

Mufreesboro Common School, Mufreesboro, Tennessee, approximately 1808-1813. Here Sarah Childress would have received the basic instructions of reading, writing and arithmetic.

Bradley Academy, Mufreesboro, Tennessee, approximately 1814-1816, A boy’s private school which their brother Anderson attended, Sarah and Susan Childress were privately tutored by its principal Samuel Black after regular school hours

Abercrombie’s Boarding School, Nashville, Tennessee, approximately 1816-1817. Sarah and Susan Childress boarded at the home of a Colonel Butler. They were sent to this school because their father’s brother John Childress, a judge, sent his daughters Matilda and Elizabeth here. More of a finishing school of young women, here Sarah Childress Polk learned to play the piano, sewing and social etiquette. Her uncle was a judge, and it was in his home that Sarah Childress Polk first came to meet and befriend Andrew Jackson, a friend and professional associate of her uncle. However, Sarah Polk was also familiar with Jackson during his visits to a plantation home where her parents had moved the family briefly, sometime prior to 1816, when Murfreesboro was made the state capital for the next ten years.

Moravian Female Academy, Salem, North Carolina, 5 May 1817 – 19 August 1819: Sarah and Susan Childress travelled the 500 mile distance here from their home on horseback, accompanied by a slave owned by their father and their  brother Anderson, who was then enrolled at the nearby University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The typical young women’s curriculum for that period would indicate that the Childress sisters were instructed in English grammar, Bible study, Greek and Roman literature, geography, music, drawing, and sewing. A lifelong love of in-depth reading was inculcated in Sarah Childress at the school. Their education here was abruptly cut short with news of their father’s sudden death and their return home. brother Anderson, who was then enrolled at the nearby University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The typical young women’s curriculum for that period would indicate that the Childress sisters were instructed in English grammar, Bible study, Greek and Roman literature, geography, music, drawing, and sewing. A lifelong love of in-depth reading was inculcated in Sarah Childress at the school. Their education here was abruptly cut short with news of their father’s sudden death and their return home.

Marriage:

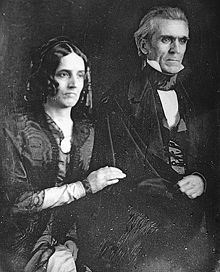

1 January 1824, Rutherford County, Tennessee; married to James Knox Polk, lawyer and state legislator, (born, 2 November 1795, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina; died, 15 June 1849, Nashville, Tennessee) While James K. Polk was a Tennessee Legislator, he began courting Miss Childress, and on January 1, 1824, James and Sarah were married at her mother’s home near Murfreesboro, Tennessee.

Children:

There is no documentation to indicate that Sarah Polk was ever pregnant, as one 20th century account later claimed. There is documentation, however, that James Polk underwent surgery before marriage to remove a urinary bladder stone that thought the operation proved successful, it left him sterile.

However, the Polks later helped raise the troubled and orphaned young adult son of Polk’s brother, Marshall Polk. Following the death of her father-in-law, she and Polk assumed much of the responsibility for raising his two youngest brothers, Sam and Bill, neither of whom was rarely out of trouble, the former requiring extensive travel in search of medical care and the latter convicted of murder.

As was then a common custom in the southern states, many young women relatives also spent the winter social season with the Polks, notably Sarah Polk’s sister’s daughter, Joanna Rucker, who wrote extensively of her experiences. Shortly after her husband’s death in 1845, Mrs. Polk assumed guardianship of a great-niece, Sally Jetton. Although she did not legally adopt her, Sarah Polk had the lifelong companionship of the girl and later, after her marriage, her husband and daughter also resided there.

Life before the White House

Sarah Childress had met James K. Polk when he was serving as clerk of the Tennessee Senate, a position he held from 1821, having been admitted to the bar the previous year. Anecdotal tradition claims that she teased him that they would marry only after he had been elected to political office in his own right. At the completion of his service as senate clerk, he was elected to the state legislature, in 1823, and they married the following year.

They moved to his family’s base in Columbia for the duration of his tenure as a state congressman, the two years following their marriage. Although they lived in a small cottage on his family’s property, larger scale entertaining and social gatherings were held at his parents’ home. This led to an unusual circumstance for a woman of her class status and era, for it left Sarah Polk without any responsibility for organizing and maintaining her own household.

This factor, in combination with her freedom from the physical duress, and emotional energy of pregnancy and subsequent child care, is what permitted Sarah Polk the time to focus her life instead on her husband’s political career. The observations of others indicate that, unlike most First Ladies which preceded her, she fully shared her husband’s ambitions to rise into national politics. To that end, she became a manager of his public schedule and correspondence and an advisor to him in both practical matters and political ones.

In 1825, following his election to the United States Congress, James Polk left for Washington, D.C. with Sarah Polk remaining home in Tennessee. During their initial separation, she began the task, apparently self-imposed, of reporting to her husband the details and news of state and local political incidents in Tennessee. Disliking their separation, Polk insisted that she return with him to Washington in 1826. Living in a boardinghouse and without the care of children, Sarah Polk was one of the few political wives who were able to move to the capital city and fully engage in social interactions with her husband’s male colleagues. Apart from her husband, she formed numerous alliances with male political figures from the Cabinet, Supreme Court, Senate and House, although they were almost exclusively also Democrats, like her husband. In 1825, following his election to the United States Congress, James Polk left for Washington, D.C. with Sarah Polk remaining home in Tennessee. During their initial separation, she began the task, apparently self-imposed, of reporting to her husband the details and news of state and local political incidents in Tennessee. Disliking their separation, Polk insisted that she return with him to Washington in 1826. Living in a boardinghouse and without the care of children, Sarah Polk was one of the few political wives who were able to move to the capital city and fully engage in social interactions with her husband’s male colleagues. Apart from her husband, she formed numerous alliances with male political figures from the Cabinet, Supreme Court, Senate and House, although they were almost exclusively also Democrats, like her husband.

Her family friendship with Andrew Jackson only further strengthened James Polk’s existing bond with his mentor and both Polks rose to a more prominent status during Jackson’s two terms as President (1829-1837). During the 1830-1831 congressional season, however, Sarah Polk remained in Tennessee. It was a deft measure which allowed her to avoid the contentious social-political “Mrs. Eaton” crisis which had President Jackson testing the loyalty of his political acolytes based on whether their wives would do as he wished and socially receive the scandalous and alienated War Secretary’s wife. Siding with the women who boycotted Mrs. Eaton, yet not wanting to damage her husband’s favored status with Jackson, Sarah Polk proved successful. Jackson’s continuing personal support was a factor in Polk’s election to the powerful position of Speaker of the House (1835-1839). When the popular but sickly Jackson’s tenure ended, the Polks had the honor of escorting him back to Tennessee, further increasing their national status.

While the Polks were in Washington, they were accompanied by two slaves, a male and female to assist them, respectively. One aspect of Sarah Polk’s crucial role in helping to maintain her husband’s political rise was her business acuity. In 1834, Polk determined to accumulate wealth through a farm factory in Grenada, Mississippi, located in Yalobusha County, where he purchased land for cotton production. It was not a southern plantation where there was a large house for the Polks to live. While Sarah Polk was home in Tennessee, James Polk instructed her on the supplies to be ordered to begin the venture, and during a congressional recess they both went to inspect their venture. The forced labor of African-American slaves presented neither Polk with any moral conflict, despite particularly Sarah Polk’s strict religious views. On the other hand, the couple would dismiss any white overseer who was reported as treating the slaves harshly, and also ensured that medical care and religious training was provided to the slaves. In making the effort to keep African-American slave families together, they also bought the spouses of those who had been previously separated to reunite them.

When Polk ran for Governor of Tennessee in 1839, the specifics of Sarah Polk’s political role in her husband’s career emerged more definitively. As her correspondence from the period showed, as he travelled the state speaking, she handled all of his incoming and outgoing correspondence, coordinating further the schedule of his speaking engagements, reviewing all the state newspapers and reporting the content to him, while ordering multiple copies of papers carrying supportive editorials, cutting them out and sending the clippings to key political figures. Polk meanwhile reported the most minute details of each district and how support for his candidacy was progressing. Winning the election, the couple moved to the capital city of Nashville in October of that year. When Polk ran for Governor of Tennessee in 1839, the specifics of Sarah Polk’s political role in her husband’s career emerged more definitively. As her correspondence from the period showed, as he travelled the state speaking, she handled all of his incoming and outgoing correspondence, coordinating further the schedule of his speaking engagements, reviewing all the state newspapers and reporting the content to him, while ordering multiple copies of papers carrying supportive editorials, cutting them out and sending the clippings to key political figures. Polk meanwhile reported the most minute details of each district and how support for his candidacy was progressing. Winning the election, the couple moved to the capital city of Nashville in October of that year.

Letters of Sarah Polk to her husband in 1840 and 1841 are especially revealing, with her highly detailed factual reports of political news she had either learned during discussions with male legislators in Nashville or from the state’s three primary newspapers, The Republic Banner, The Nashville Union and The Nashville Whig. With her husband conducting his re-election speaking tour of the state in 1841, she provided him with bullet-point information from Nashville. Despite her support, Polk lost not only his re-election bid, but the subsequent race for governor, in 1843.

Having lost in his campaign for re-election in 1840, it was widely believed that former President Martin Van Buren would be the Democratic presidential candidate in 1844, at the blessing of the “father” of the party, former President Jackson. Van Buren’s opposition to the annexation of Texas, however, put him in conflict with Jackson and he lost support. The Polks, like Jackson, were avid advocates of expansionism, including to the Pacific Ocean, and Polk won the support of his mentor for the party’s nomination.

Campaign and Inauguration

Never in robust health, James Polk had a tendency to work until the early morning hours at the risk of his well-being. Both out of concern for his health and her ambition for him to win the presidency, Sarah Polk worked alongside him from their base operation at home in Columbia, maintaining an extensive national correspondence with party leaders. Besides writing to individuals, she is also believed to have implored regional newspaper editors to express support for Polk in their publications’ editorials, and providing summary reports of his specific intentions as President, largely related to expansionism.

Following Polk’s election to the presidency, Sarah Polk joined him in a victory celebration at Nashville. From there they proceeded to the capital via stagecoach, steamboat, and rail. When the president-elect’s wife forbade a well-intentioned band of musicians from playing music on a Sunday, however, she forecast the tempo of her tenure. Following Polk’s election to the presidency, Sarah Polk joined him in a victory celebration at Nashville. From there they proceeded to the capital via stagecoach, steamboat, and rail. When the president-elect’s wife forbade a well-intentioned band of musicians from playing music on a Sunday, however, she forecast the tempo of her tenure.

Seated with prominent visibility at her husband’s swearing-in ceremony in a heavy rainstorm, she appeared at the two Inaugural balls held that evening, one charging a ticket price of five dollars, the other at ten dollars. When she came to the balcony to review celebrants at the latter event, held at the National Theater where a platform over the orchestral seating provided a temporary dance floor, the music suddenly stopped in deference to her wishes.

First Lady

4 March 1845 – 4 March 1849

An orthodox Christian who belonged to the Presbyterian Church, Sarah Polk’s incumbency of the White House was marked by a sober tone. Known as a strict “Sabbatarian,” she refused to permit any business to be conducted on Sundays, famously once having the new Austrian Minister turned away when he came to present his credentials to the President.

Although she continued her longstanding refusal to attend the racetrack where gambling took place and also barred dancing in the White House, she never delineated that either of these decisions were based on her religious views. Although music for dancing or other entertainment of invited guests was not provided at the White House, the Marine Band did introduce the appearance of the President by playing the martial air that came to be known as “Hail to the Chief,” said to be a continuance of a custom begun by her predecessor Julia Tyler. While there is no evidence that she specifically banned the public concerts held on the lawn for the general public, also begun in the Tyler Administration, there are also no firsthand accounts by those who may have attended them if, in fact, they were continued. Sarah Polk did refuse to continue serving whiskey, beer and other alcoholic beverages other than wine, which was only served to dinner guests. Neither Polk, however, indulged in the wine. Although she continued her longstanding refusal to attend the racetrack where gambling took place and also barred dancing in the White House, she never delineated that either of these decisions were based on her religious views. Although music for dancing or other entertainment of invited guests was not provided at the White House, the Marine Band did introduce the appearance of the President by playing the martial air that came to be known as “Hail to the Chief,” said to be a continuance of a custom begun by her predecessor Julia Tyler. While there is no evidence that she specifically banned the public concerts held on the lawn for the general public, also begun in the Tyler Administration, there are also no firsthand accounts by those who may have attended them if, in fact, they were continued. Sarah Polk did refuse to continue serving whiskey, beer and other alcoholic beverages other than wine, which was only served to dinner guests. Neither Polk, however, indulged in the wine.

Since not all of the restrictions enacted during the Administration can be traced to Sarah Polk’s personal religious views, some may have been unfairly ascribed to her, as opposed to the President. While he was not as strictly religious as his wife, James Polk resented any intrusion into his work time, especially if it involved what he considered to be a frivolous distraction, a famous example being when a juggler was invited to perform for guests and he resented the time lost as he politely sat through the demonstration. Another factor which affected entertaining at the White House was the fact that Sarah Polk had no previous experience running a large household or entertaining on a large scale. The general public had the chance to meet her at one of her twice a week open-house receptions. In the White House, she left management of event to the household staff. On one occasion, as she sat down for a formal dinner, another guest had to point out the fact that there were no napkins at the table settings. Since not all of the restrictions enacted during the Administration can be traced to Sarah Polk’s personal religious views, some may have been unfairly ascribed to her, as opposed to the President. While he was not as strictly religious as his wife, James Polk resented any intrusion into his work time, especially if it involved what he considered to be a frivolous distraction, a famous example being when a juggler was invited to perform for guests and he resented the time lost as he politely sat through the demonstration. Another factor which affected entertaining at the White House was the fact that Sarah Polk had no previous experience running a large household or entertaining on a large scale. The general public had the chance to meet her at one of her twice a week open-house receptions. In the White House, she left management of event to the household staff. On one occasion, as she sat down for a formal dinner, another guest had to point out the fact that there were no napkins at the table settings.

Another time, she became so engrossed in a conversation that she failed to even touch the food on her dinner plate. Another factor was her concern for the cost of entertaining which was borne as a personal expense to presidential families at the time. Initially, Sarah Polk even considered renting a small private home for herself and the President to live in, using the executive mansion only as an office and occasional setting for ceremonies. Ultimately, she cut the jobs of ten household staff members to save money, their work being done by African-American slaves that she owned or purchased at the time from Polk relatives. She had basement rooms remodeled as their living quarters.

Sarah Polk’s political role continued to evolve in response to the needs of her husband. It was the First Lady, for example, not the President who often greeted members of Congress, enjoying in-depth discussions on legislation or other pending issues when they called for the President on Saturday afternoons (likely as a result of not being in working sessions that day). Since the Polks were so often together during their White House tenure, there were few letters between them from which can be derived definitive examples of her widely acknowledged political acumen. One source claims that she “read and passed judgment” on the President’s speeches, though there is no documented citation for this. Sarah Polk’s political role continued to evolve in response to the needs of her husband. It was the First Lady, for example, not the President who often greeted members of Congress, enjoying in-depth discussions on legislation or other pending issues when they called for the President on Saturday afternoons (likely as a result of not being in working sessions that day). Since the Polks were so often together during their White House tenure, there were few letters between them from which can be derived definitive examples of her widely acknowledged political acumen. One source claims that she “read and passed judgment” on the President’s speeches, though there is no documented citation for this.

It is established that in the presidential offices, adjacent to the family living quarters, Sarah Polk continued her work as her husband’s personal secretary, clipping news stories and editorials, reading, processing and filing incoming correspondence and pulling aside those items she judged to be important enough to bring to the President’s attention. Considering that Polk rarely consulted his Cabinet and disliked frequent and direct interaction with the general public, Sarah Polk played another crucial role as his liaison to the outside world, a filter through which issues and information reached his attention. As she long had, Sarah Polk not only absorbed information from male political figures but from the President, in reaction to what she brought to him. Her ultimate right of denial to access of the President was overtly acknowledged in letters from and remarks made to her by members of the Cabinet, Supreme Court, Congress and military, including Henry Clay, Henry Gilpin, Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan. Vice President George Dallas, whose access to the President was limited, nursed some resentment towards the First Lady for her status, remarking, “She is certainly master of herself and I suspect of someone else also.”

The President as much admitted this, remarking famously, “None but Sarah knew so intimately my private affairs.” The First Lady nevertheless exercised a degree of discretion when she discussed political issues with political figures, obfuscating whether she was articulating her own personal view or simply parroting those of Polk. She did this by routinely introducing her remarks by suggesting they were the opinions of the President. The President as much admitted this, remarking famously, “None but Sarah knew so intimately my private affairs.” The First Lady nevertheless exercised a degree of discretion when she discussed political issues with political figures, obfuscating whether she was articulating her own personal view or simply parroting those of Polk. She did this by routinely introducing her remarks by suggesting they were the opinions of the President.

There was at least one major political issue on which Sarah Polk disagreed with her husband, the full implementation of a federal banking system. Since his first congressional term, Polk had shared President Andrew Jackson’s staunch opposition to a national banking operation for the U.S. government which would permit the issuing of paper currency to represent the physical gold and silver coins which would back it and remain in a federal reserve. Decidedly anti- hard-money, Sarah Polk failed to convince her husband to her view that it was an inconvenient and antiquated system. Sarah Polk had a more open view of technological changes, countering her husband’s reliance on steamboats with suggestions that they begin using the steam-engine railroads when possible. At the White House, she approved the conversion of lighting to gas, although she decided to keep one room still lit entirely by candle.

In line with the traditional Calvinism of her faith, Sarah Polk claimed to believe that God had pre-determined the roles to be played by individual human beings and the events they would face. Using this perspective, she once famously defended the enslavement of African-Americans as ordained, explaining to her husband that they were created for their lot in life as much as she and the President were. One chronicler concluded that she took a similar attitude in justifying her husband’s decision to deny those Cherokee Indians removed from their property in the South to the western territory any access to public education other than that for manual labor and in areas restricted to their reservations.

She similarly shared Polk’s view of “Manifest Destiny,” the idea that it was part of a larger, ordained plan for the United States to extend its borders through the Oregon Territory to the West and throughout the Mexican-bordered southwestern region. There are no specific examples of the First Lady expressing her views or reflecting on the Mexican War other than ceremonial acts and her acceptance of gifts from two high-ranking generals of the conflict, Gideon Pillow and William Worth.

One incident illustrated an effort she made to keep morale for the war raised, as when she asked a lieutenant recently returned from the bloody conflict between American and Mexican troops at Monterey regale those gathered around him with heroic tales of the battlefield.

Mrs. Polk later expressed her belief that the acquisition of California and New Mexico, resulting from the war, were among the most important turning points in the nation’s history. To those who voiced opposition to the conflict, she simply replied that there was “always someone opposed to everything.” A more startling remark, recorded by a dinner guest seated beside the First Lady was her remark that “whatever sustained the honor and advanced the interests of the country, whether regarded as democratic or not, she admired and applauded.” Mrs. Polk later expressed her belief that the acquisition of California and New Mexico, resulting from the war, were among the most important turning points in the nation’s history. To those who voiced opposition to the conflict, she simply replied that there was “always someone opposed to everything.” A more startling remark, recorded by a dinner guest seated beside the First Lady was her remark that “whatever sustained the honor and advanced the interests of the country, whether regarded as democratic or not, she admired and applauded.”

Although the Seneca Falls Convention for Women’s Rights was held in Seneca Fall, New York during Sarah Polk’s tenure as First Lady, the call made by the gathered women for the right to vote and to address other gender inequalities was considered radical by most citizens at the time. In one instance, following a working woman’s remarks that she was making her first visit to the White House, Sarah Polk observed to others that this was to be expected because the woman’s need for employment indicated that she was of a lower status than that of women like herself who were married to successful men.

Life after the White House

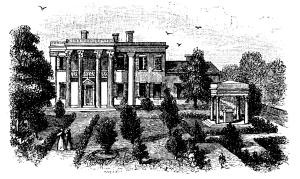

Following the end of his presidency, James Polk returned to Nashville with Sarah Polk, moving into a new home they had renovated, to be known as “Polk Place.” Throughout her marriage, Sarah Polk had sought to discourage her husband’s tendency to overwork. James Polk had physically deteriorated by his killing work load as President.

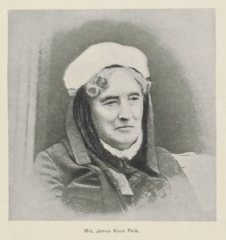

Highly vulnerable during a cholera outbreak, he died three months after leaving office. Widowed at age 45 years old, Sarah Polk rarely left Polk Place for the nearly four decades that she survived him, except for attending church on Sundays and several visits to his and her family members in nearby Columbia and Murfreesboro. Highly vulnerable during a cholera outbreak, he died three months after leaving office. Widowed at age 45 years old, Sarah Polk rarely left Polk Place for the nearly four decades that she survived him, except for attending church on Sundays and several visits to his and her family members in nearby Columbia and Murfreesboro.

In 1850, Sarah Polk did travel to inspect her Mississippi cotton plantation. As a slave-owner, Sarah Polk has a mixed record. There was a high infant mortality rate and while she claimed that she wished not to sell individuals and break up families, she did so if it meant a profit. On the other hand, she saw to it that the individual slaves were provided with both medical care and religious training. Whether it was declining profits or her own political savvy in detecting the imminent outbreak of the Civil War and eventual emancipation of slaves, she sold her plantation and slaves in 1860, a year before the war began. In 1850, Sarah Polk did travel to inspect her Mississippi cotton plantation. As a slave-owner, Sarah Polk has a mixed record. There was a high infant mortality rate and while she claimed that she wished not to sell individuals and break up families, she did so if it meant a profit. On the other hand, she saw to it that the individual slaves were provided with both medical care and religious training. Whether it was declining profits or her own political savvy in detecting the imminent outbreak of the Civil War and eventual emancipation of slaves, she sold her plantation and slaves in 1860, a year before the war began.

During the Civil War, Sarah Polk declared herself neutral and welcomed both Union and Confederate military leaders to her home. When, however, she was asked to sign an oath of loyalty to the Union, as was required of all Nashville residents seeking to obtain coal, she refused. Later she admitted that her sympathies were with the South and she blamed the divisions within the Democratic Party during the 1860 election for the outbreak of war, believing the conflict could have been avoided through legislation.

At Polk Place, the presidential widow essentially created a shrine and museum there to her late husband, displaying mementos and historical objects associated with him and his Administration, his photographs and portraits, as well as his extensive presidential papers. When historian George Bancroft began research and completed some writing about the Polk Administration, Sarah Polk willingly shared material with him and even loaned some papers, which she sent by mail to Washington. At Polk Place, the presidential widow essentially created a shrine and museum there to her late husband, displaying mementos and historical objects associated with him and his Administration, his photographs and portraits, as well as his extensive presidential papers. When historian George Bancroft began research and completed some writing about the Polk Administration, Sarah Polk willingly shared material with him and even loaned some papers, which she sent by mail to Washington.

Although she lived in relative isolation, removed from the realities of the Reconstruction South, she did maintain her interest in emerging technologies and had both a telegraph and telephone installed in her home.

She was later given the honor of opening Cincinnati’s Centennial Exposition, by pressing an electric button connected by telegraph to the fair, setting the machinery in motion to signal the start of the event. Among her many distinguished guests were President and Mrs. Hayes in 1877. Later, when the Women’s Christian Temperance Union assembled testimonies to honor Lucy Hayes, her fellow temperance First Lady Sarah Polk was the first to sign the book. During the 1887 visit by President and Mrs. Cleveland, Sarah Polk spoke extensively with them about the rooms and changes made since she lived in the White House. She was later given the honor of opening Cincinnati’s Centennial Exposition, by pressing an electric button connected by telegraph to the fair, setting the machinery in motion to signal the start of the event. Among her many distinguished guests were President and Mrs. Hayes in 1877. Later, when the Women’s Christian Temperance Union assembled testimonies to honor Lucy Hayes, her fellow temperance First Lady Sarah Polk was the first to sign the book. During the 1887 visit by President and Mrs. Cleveland, Sarah Polk spoke extensively with them about the rooms and changes made since she lived in the White House.

Although she assiduously responded to all the public inquiries and requests which came her way, she resisted the urgings of her friends to record aspects of her own biography and experiences, focusing always on her late husband’s life.

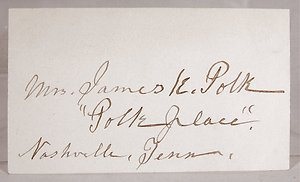

She always identified herself as “Mrs. James K. Polk,” using Sarah Polk only on legal documents.

Death Death

14 August 1891

Nashville, Tennessee.

Burial

Nashville, Tennessee

Although Sarah Polk was buried with her husband in his tomb on the front lawn of their home, their home was razed against the expressed wishes of their wills. Their burial site is located near the Tennessee capital building.

|