|

Copyright, Attention: This website and its contents contain intellectual property copyright materials and works belonging to the National First Ladies’ Library and Historic Site and to other third parties. Please do not plagiarize. If you use a direct quote from our website please cite your reference and provide a link back to the source.

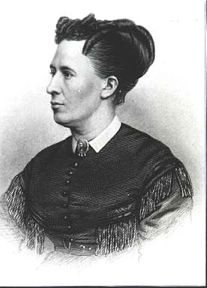

First Lady Biography: Julia Grant

Julia Boggs Dent Grant

Born:

26 January 1826

“White Haven” farm

St. Louis, Missouri

Father:

Frederick Fayette Dent, born 6 October 1786, Cumberland, Maryland; died 16 December 1873, the White House, Washington, D.C. Frederick Fayette Dent, born 6 October 1786, Cumberland, Maryland; died 16 December 1873, the White House, Washington, D.C.

Frederick Dent was one of five children between his parents, and also the half-brother of a son by his mother’s first marriage. His father George Dent was the surveyor of what would become Cumberland, Maryland and helped determine the town’s layout. Frederick Dent was born in a loghouse, but as family finances improved, it was torn down and replaced by a brick structure. Although he had no formal education, Frederick Dent was successful as a merchant early in life, leaving Cumberland in 1806 as an apprentice to David Shriver, who surveyed and cleared the land for the creation of a national road from Cumberland to what is now Wheeling, West Virginia. At some point shortly thereafter, he moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he met his future wife.

After relocating to Missouri Territory in 1816, he formed a partnership with George W. Rearick and later with Edward Tracey in St. Louis. His firm thrived to the point where he was able to retire as something of a country squire when Julia Dent was still young. He successfully invested in the purchase of one of the earliest known commercial steamboats, and employed it to begin trading along the Mississippi River, transporting such goods as coffee and sugar from New Orleans. Although he held no military rank, he took on the moniker of colonel, suggesting a southern plantation slave owner.

Mother:

Ellen Bray Wrenshall, born April 1793, Lancashire, England; married 22 December 1814, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; died 14 January 1857. Ellen Bray Wrenshall, born April 1793, Lancashire, England; married 22 December 1814, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; died 14 January 1857.

Ellen Wrenshall immigrated to the United States with her parents, six sisters and one brother, according to her daughter, “at a very early age,” although the exact year is unknown. Her father John was a successful merchant of the British exporting firm Wrenshall, Peacock & Pillon, which primarily drew its profits by importing ginseng root to China. The family settled in Philadelphia. Although she grew up in a wealthy household, Mrs. Grant’s mother lived a socially restricted childhood, dictated by the rigorous adherence to Methodist principals which forbid dancing, card-playing and any alcohol consumption. She nevertheless received a finishing-school education in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the name of which is unknown. One of the highlights of her younger years was being given shelter by Aaron Burr and his militia at an Alleghany Mountain tavern as she travelled from school back home to Philadelphia.

In 1816, Julia Dent’s parents and their first child relocated from Pittsburgh to what was then a frontier country known as “Upper Louisiana,” which became St. Louis, Missouri, making the trip by flatboat and carriage.

Birth Order and Siblings:

Fifth of eight, four brothers, three sisters; John Cromwell Dent (1816-1889); George Wrenshall Dent (1819-1899); Frederick Tracy Dent (1820-1892); Louis Dent (1823-1874); Ellen “Nellie” Wrenshall Dent [Sharp] (1828-1885); Mary Dent (1825, died in infancy); Emily “Emma” Marbury Dent Casey (1836-1920)

Ancestry:

All of Julia Dent Grant’s ancestors were English in origin. Her paternal grandfather’s ancestor was Thomas Dent of Yorkshire, England, who immigrated in 1643 and settled near what would become the Washington, D.C. area, in Bladensburg, Maryland; her paternal grandfather George Dent was born there. Julia Grant claimed that her paternal grandmother’s name was Susanna Marbury and that her ancestors were wealthy landowners from Cheshire, England who made their home at an estate called Marburg Hall. This conflicts with several detailed genealogical records that indicate that her paternal grandmother was born as Susannah Dawson, and was the widow of a Joseph Dawson. Julia Grant did not seem to have invented this more aristocratic aspect of her ancestry, however, for she possessed an engraving of Marbury Hall on the assumption that it was an ancestral home, and one of her sisters was given the middle name of Marbury. After their marriage, her paternal grandparents George Dent and Susannah Dawson Cromwell relocated to Cumberland, Maryland. Julia Grant’s mother was an English immigrant. (see “Mother” entry above)

Religion

Methodist. Throughout her entire life, Julia Dent Grant was a regular church-goer and made an effort early on to ensure her children received a religious education. She did not, however, ever refrain from some of the “worldly” pleasures such as alcohol consumption, dancing, and gambling either through betting at horse races and card-playing, which the strictest adherence to the faith insisted upon.

Childhood Home:

Shortly before Julia Dent’s birth, her parents purchased a spacious wood clapboard house, intended to serve as a summer home. Located about ten miles south of St. Louis in a heavily one-thousand acre wooded area through which ran Gravois Creek, Frederick Dent named it “White Haven,” after one of his alleged ancestral homes in England. Dent made it a working farm, and purchased one of the region’s first crop thresher machines, drawing crowds of curious locals to see the new invention in action. Various working animals on the farm were imported, such as donkeys from Malta, and pigs from China.

Education:

The Gravois School, St. Louis, Missouri, (approximately 1831-1836).

Details about the institution where Julia Dent received her first formal education are sparse. Described as a one-room schoolhouse made of logs, there were at least four male instructors, two of whom had been trained for higher education. One of the teachers was John F. Long, a farmer and neighbor of the Dents and later a friend to Ulysses Grant as well. Julia Grant remembered more about the classroom being divided between boys and girls and older and younger students, the fireplace and flowers inside and the playground outside, than she did about any of her studies.

Mauro Academy for Young Ladies, St. Louis, Missouri, (1836-1843).

Attending this private girls school in downtown St. Louis from the age of ten until seventeen meant that Julia Dent was a boarding student during the week, returning home to White Haven on weekends, usually escorted by a teacher or older student who remained as guests until returning to the city Run by a Mr. P. Mauro and his daughters, the school was located at Fifth and Market Streets. By her own account, Julia Dent “devoted” herself to history, mythology, and philosophy, disliked grammar, mathematics, and was “below the standard” in all other subjects. She later stated that she was permitted to “select my own studies” at the Moreau School. Attending this private girls school in downtown St. Louis from the age of ten until seventeen meant that Julia Dent was a boarding student during the week, returning home to White Haven on weekends, usually escorted by a teacher or older student who remained as guests until returning to the city Run by a Mr. P. Mauro and his daughters, the school was located at Fifth and Market Streets. By her own account, Julia Dent “devoted” herself to history, mythology, and philosophy, disliked grammar, mathematics, and was “below the standard” in all other subjects. She later stated that she was permitted to “select my own studies” at the Moreau School.

During her latter school years, Julia Dent developed a lifelong passion for voraciously reading novels. Apart from her early formal education, she also learned the literature of classic literature and poetry from readings by her mother. However, she especially credited her brother Louis, to whom she was closest among her four brothers, for engaging her in reading and reciting the works of Shakespeare and Byron.

Life before Marriage:

Skilled at the piano, Julia Dent enjoyed playing music and singing in accompaniment to traditional Scottish ballads and contemporary compositions popular in the southern states. She also displayed a degree of artistic skill in various forms. She was an accurate at capturing images in hand-drawn sketches, even devising the basic configuration of their “Hardscrabble” cabin.

While Julia Grant later recalled her mother as a loving and sweet presence, it was her father’s first cousin Ruth Caroline Schutz O’Fallon, a Baltimore heiress whose stylish home was in St. Louis who inculcated her in the finer points of social life among the elite. “Society” was an important aspect of her life from young adulthood until her death.

Her father’s politics were shaped by his economic fortune, which was based in slavery. Frederick Dent retained about thirty enslaved African-Americans and refused to consider freeing them on moral ground, doing so only when compelled by law of emancipation. His anti-abolitionist principals also guided his political loyalty to the Jacksonian wing of the Democratic Party and rabidly anti-Whig and then anti-Republican.

As would be true with even the more difficult periods of her life, Julia Dent Grant left highly colorful, idealized recollections of her early years. The nature of the Dent household was highly social, with White Haven visitors coming from among the elite class of Cincinnati, Louisville and Pittsburgh. Frederick Dent also counted Missouri Territorial Governor William Clark, one of two principals of the famous Lewis and Clark Expedition to the west, and Alexander McNair, the first state governor of Missouri, among his close friends; thus Julia Dent Grant was familiar and comfortable with powerful political figures early in life.

By her own admission, Julia Grant had been greatly indulged by her parents yet maintained that she was not spoiled. Her brothers often included her in activities such as fishing, and hunting of squirrel, foxes, rabbits, quail, grouse, pheasant, geese, ducks, turkeys, crane, doves, plover and woodcocks. She was also an expert horsewoman, especially attached to her horse Psyche, and would remain devoted to both riding and attending horse races for the rest of her life. By her own admission, Julia Grant had been greatly indulged by her parents yet maintained that she was not spoiled. Her brothers often included her in activities such as fishing, and hunting of squirrel, foxes, rabbits, quail, grouse, pheasant, geese, ducks, turkeys, crane, doves, plover and woodcocks. She was also an expert horsewoman, especially attached to her horse Psyche, and would remain devoted to both riding and attending horse races for the rest of her life.

Frederick Dent had brought to Missouri from Maryland a number of slaves, and later purchased others, holding nearly twenty African-Americans in bondage as property in the 1850s. The First Lady claimed to believe that “our people,” meaning the Dent slaves, were “very happy,” and that only at the onset of the Civil War did the younger generation of slaves become “somewhat demoralized,” claiming either willfully or naively that it was their reaction to “all the comforts of slavery” ending with emancipation. She referred to the older generation of African-American as her “aunts” and “uncles” and recalled that she often interceded on their behalf to obtain small amounts of money, tobacco, sugar and other amenities.

Upon her graduation from the Mauro Academy, Julia Dent often visited schoolmates at their homes in St. Louis or the Jefferson Barracks, a U.S. Army base located about halfway between St. Louis and White Haven. The maturing Miss Dent came to meet many young officers, becoming especially acquainted with those who came to visit her brother Fred, an officer, during his periods on leave from Fort Towson in Indian Territory. Upon her graduation from the Mauro Academy, Julia Dent often visited schoolmates at their homes in St. Louis or the Jefferson Barracks, a U.S. Army base located about halfway between St. Louis and White Haven. The maturing Miss Dent came to meet many young officers, becoming especially acquainted with those who came to visit her brother Fred, an officer, during his periods on leave from Fort Towson in Indian Territory.

During his education at West Point Academy, Fred Dent wrote his sister Julia about how impressed he was with a fellow student, Ulysses S. Grant. “I want you to know him,” he wrote his sister, “he is pure gold.” Fred Dent had also spoken to Grant about his sister. In 1844, as a young lieutenant Grant began to routinely visit the Dent family at White Haven.  In April of that year, he made what seemed like another routine call, but sat outside on the porch with Julia Dent, rather than her brother, and asked her to accept and wear his class ring, as a sign of their exclusive affection. Eighteen years old at the time, she initially demurred from accepting. Grant’s regiment was then ordered to Louisiana, in preparation for service in the Mexican War. Distraught at their separation, Miss Dent had an intense dream, which she detailed to several people, that Grant would somehow return within days, wearing civilian clothes and state his intention of staying for a week. In April of that year, he made what seemed like another routine call, but sat outside on the porch with Julia Dent, rather than her brother, and asked her to accept and wear his class ring, as a sign of their exclusive affection. Eighteen years old at the time, she initially demurred from accepting. Grant’s regiment was then ordered to Louisiana, in preparation for service in the Mexican War. Distraught at their separation, Miss Dent had an intense dream, which she detailed to several people, that Grant would somehow return within days, wearing civilian clothes and state his intention of staying for a week.

Despite the seeming impossibility of this, circumstances permitted Grant to return precisely as Julia had dreamed he would. It was but the first example of a lifetime of dreams and other extra-sensory perception experiences by which she often found comfort or made decisions of calculable risk. During this period, Grant declared his love for Miss Dent. Claiming she would not mind being engaged to him without committing to marry him, it was enough of an assurance that Grant approached her father for permission to marry.

Colonel Dent made clear his personal affection for Grant, but expressed the belief that Julia had been accustomed to a comfortable lifestyle and would be unable to adapt to the rigor of the harsh and unpredictable life that being married to a career military husband would require. Grant declared that he was so determined to marry Julia Dent that he would accept an offer made to him of becoming a professor of mathematics at a Hillsboro, Ohio college. Dent suggested he remain in the U.S. Army and that he and Julia wait for about two years before reconsidering marriage. As

events would prove, it would be four years, not until 1848 as Grant returned from his service in the Mexican War that the couple again saw each other.

During the period of her long separation from Grant, Julia Dent did not deny herself the harmless flirtations of responding to young men who serenaded her and her sister Ellen outside of their windows. Nevertheless, she and Grant maintained an intense correspondence, Grant often composing his letters from his tent on the battlefields. When once there was a period of a month when she received no letter, Julia Dent had another dream that her name appeared in a newspaper listed as being the recipient of letters without a proper address – and like her previous dream related to Grant, it proved true.

In late July of 1848, Grant returned from the war and suggested to Julia that they marry as soon as possible. After waiting four years, Julia Dent was eager to comply.

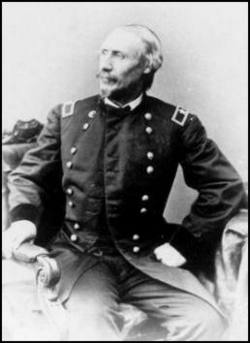

Marriage:

22 years old, married 22 August 1848, St. Louis, Missouri, to Hiram Ulysses Grant born 27 April 1822, Point Pleasant, Ohio, died 23 July 1885, Mount McGregor, Saratoga Springs, New York. Contrary to wide belief, Grant’s middle name was not “Simpson,” and he later confessed that his taking of the middle initial of “S.” was merely an affectation. Grant had graduated from West Point on 1 July 1843, ranked twenty-first in a class of thirty-nine. At the time of the marriage, he held the rank of brevet second lieutenant. During the Mexican War, he served as quartermaster.

The Dent-Grant wedding took place at the Dent family home in St. Louis on the corner of Cerre and Fourth Street. Since many of her friends were out of the city due to the summer heat, the wedding was small, but elegant. Although she had intended on wearing a simple and light Indian muslin gown for the ceremony, Julia Dent was delighted at the gift of an elegant watered silk white wedding gown and veil of white fringed tulle, presented by her O’Fallon relatives. There was a lavish wedding cake, music and refreshments. Among the groomsmen were several men who would go on to fight against Grant as Confederate officers. The Dent-Grant wedding took place at the Dent family home in St. Louis on the corner of Cerre and Fourth Street. Since many of her friends were out of the city due to the summer heat, the wedding was small, but elegant. Although she had intended on wearing a simple and light Indian muslin gown for the ceremony, Julia Dent was delighted at the gift of an elegant watered silk white wedding gown and veil of white fringed tulle, presented by her O’Fallon relatives. There was a lavish wedding cake, music and refreshments. Among the groomsmen were several men who would go on to fight against Grant as Confederate officers.

Noteworthy for their absence were any members of the groom’s family. Extremely religious and vehement abolitionists, his parents Jesse and Hannah Grant did not approve of their son marrying into a family that held human beings as property. While there is no indication of any open confrontation between Grant’s parents and his wife, the lack of any effort by the senior Grants to even grudgingly express affection for their new daughter-in-law was a hurt she never forgot. According to the “Ulysses S. Grant homepage,” Grant’s letters to his father were “sometimes curt and show disapproval for his condescending attitude towards his wife, Julia, and his miserly habits when she visited.” Despite such documentation, Julia Grant left a conflicting record of their first encounter, claiming that Jesse Grant treated her “cordially,” and that Hannah Grant offered her “an affection welcome.”

The newlyweds took a three-month honeymoon excursion by riverboat and stagecoach, stopping in Louisville and then travelling through Ohio to the home of his parents and other relatives. During a visit at the lavish home of a Grant cousin, Julia Grant was impressed by how modestly her new husband suggested to a number of prominent and successful export merchants there that he would welcome a chance to enter one of their enterprises since such a business profession could provide a more financially stable life for his new wife. She was stung by the fact that none of them made any overture to help Grant and, further, that in later years she was compelled to treat politely some of these same individuals who then pressed her for favors at the direction of her then-prominent husband.

The attraction between Ulysses and Julia Grant was intense and lifelong. All documentation suggests that his mother Hannah Grant was extremely detached from her son, offering no emotional support to him. In contrast, Julia Grant provided a deep well of unconditional love and support to him. She had a series of affectionate nicknames for him, such as “Victor” (as in always the winner), Dodo, and Dudy. By conventional standards, Julia Dent Grant was often described as plain, due largely to her crossed eyes. Highly self-conscious about this physical defect, in later years she scheduled an appointment for surgery to correct it until her husband gently reminded her that he had fallen in love with her despite the appearance of her eyes. The remark convinced her to remain as she was, reminded of the secure love of her husband.

Children:

Three sons, one daughter: Frederick Dent Grant (30 May 1850 – 1912); Ulysses S. “Buck” Grant, Jr. (22 July 1852 – 1929), Ellen Wrenshall “Nellie” Grant [Sartoris] (1855 – 1922) Jesse Root Grant (1858 – 1934)

The Grant children were highly indulged with love and forgiveness, especially by their father. Horace Porter, staff officer to General Grant, later recalled that Nellie and Jesse “would hang around his neck while he was writing, making a terrible mess of the papers, and turn everything in his tent into a toy.”

Although she too indulged her children, it was Julia Grant who ultimately had to control and guide their children, turning to her husband as a last resort. As she would recollect: “The General had no idea of the government of the children. He would have allowed them to do pretty much as they pleased…Whenever they were inclined to disobey or question my authority, I would ask the General to speak to them. He would, smiling at me, and say to them, “…you must not quarrel with Mama. She knows what is best for you and you must always obey her.” Although she too indulged her children, it was Julia Grant who ultimately had to control and guide their children, turning to her husband as a last resort. As she would recollect: “The General had no idea of the government of the children. He would have allowed them to do pretty much as they pleased…Whenever they were inclined to disobey or question my authority, I would ask the General to speak to them. He would, smiling at me, and say to them, “…you must not quarrel with Mama. She knows what is best for you and you must always obey her.”

Julia Grant was affectionate and close to all of her children, never showing preference for one over the other. She named them after her mother and father, her husband and father-in-law, nicknaming the second one “Buck” to honor the fact that he was born in Ohio, the “Buckeye State.” Apart from their formal education, she provided them with a unique venue of teaching, giving them daily lessons about each object they used, detailing for them how wood furniture was from trees in Central America, glass from the sand of beaches, and wool blankets from lambs.

Life After Marriage:

Following her marriage, Julia Grant’s life was dictated by her husband’s military career. When faced with the prospect of forever leaving the home of her beloved father and childhood home, however, she experienced great anxiety until Colonel Dent suggested that the only alternative was to continue living with him while her husband returned only on leave of absence once or twice a year. Proving unacceptable to her, her husband finally asked Julia to never again express sadness at parting from her father since it made Grant unhappy to see her in such a state. The absolute faith in her husband’s abilities never wavered and it is no understatement to credit Julia Grant for the more ephemeral aspects of what would lead to her husband’s success in his public roles as General and President. Uncertain and hesitant, Ulysses S. Grant often retreated into himself; Julia Grant just as often strove to engage him. After his wife organized a Mardi Gras masquerade ball early in their marriage, for example, he would only appear in his uniform while she invested an enormous amount of energy into her costume as a gypsy. Observing her enthusiasm, he was prompted to go out and purchase a tambourine to complete her outfit, and nicknamed her “Tambourina” for a time.

In November of 1848, the couple relocated to the Detroit, Michigan, where Grant was stationed with the Fourth Infantry. Their first home there was the Michigan National Hotel but by the spring of 1849 they had managed to buy a small wood frame house at 253 East Fort Street. After a brief return home to St. Louis to give birth to her first son, the couple and their child shared quarters in the barracks with another couple. Based close enough to make regular visits to Grant’s sister Clara, the period also marked her first excursions by railroad. They would live here until 1852, although Julia Grant would make numerous visits back to St. Louis, where her first child was born, and White Haven. While there, Mrs. Grant also attended lectures given by women’s rights advocate Frederika Brewer and politician William Seward. In November of 1848, the couple relocated to the Detroit, Michigan, where Grant was stationed with the Fourth Infantry. Their first home there was the Michigan National Hotel but by the spring of 1849 they had managed to buy a small wood frame house at 253 East Fort Street. After a brief return home to St. Louis to give birth to her first son, the couple and their child shared quarters in the barracks with another couple. Based close enough to make regular visits to Grant’s sister Clara, the period also marked her first excursions by railroad. They would live here until 1852, although Julia Grant would make numerous visits back to St. Louis, where her first child was born, and White Haven. While there, Mrs. Grant also attended lectures given by women’s rights advocate Frederika Brewer and politician William Seward.

There followed a brief re-assignment during the winter of 1848-1849 to the Madison Barracks at Sackets Harbor, New York, and then again in the fall and winter of 1851-1852. For Julia Grant, it was a happy period, particularly since it permitted her to indulge a love of dancing at social events. Since it was peacetime, her husband had much free time and took up his lifetime love of card-playing. Despite both being raised as Methodists, they ignored the faith’s stricture against dancing and card-playing. During this period, Julia Grant also learned to manage her own household, hosting her first dinner party with considerable anxiety, and taking pride in furnishing their home on a small budget.

While Julia Grant readily accepted the traditional division of marital responsibility by running their home, she was also conscious of how often wives had unthinkingly exceeded the means of a husband’s salary. At Madison Barracks, she first requested that Grant provide her with a regular allowance on which she would meet the expenses of their household, an arrangement to which he agreed. Julia Grant then began keeping her own financial account books. Although she confessed to a great deficit in her ability with anything mathematical and often failing when it came to precise accuracy, she would persist in maintaining their financial records, whether they were wealthy or poor, and continued to do so until her death.

In 1852, with the rank of captain, Grant was assigned to Humboldt Bay, California on the Pacific Ocean. The distance prevented Julia Grant from joining him and the two years of separation were especially torturous for him, leading him into long bouts of depression and, some sources suggest, heavy drinking. It was a period when his emotional health especially depended on the love and faith in him that Julia expressed in her letters. In later years, Julia Grant would vociferously maintain that her husband did not develop an alcohol dependency while stationed in California. However, she may have crafted her words carefully to avoid an outright denial of his condition during their two year separation, chronicling only her feelings of being “indignant and grieved” by statements suggesting Ulysses Grant was “dejected, low-spirited, badly-dressed and even slovenly.” In 1852, with the rank of captain, Grant was assigned to Humboldt Bay, California on the Pacific Ocean. The distance prevented Julia Grant from joining him and the two years of separation were especially torturous for him, leading him into long bouts of depression and, some sources suggest, heavy drinking. It was a period when his emotional health especially depended on the love and faith in him that Julia expressed in her letters. In later years, Julia Grant would vociferously maintain that her husband did not develop an alcohol dependency while stationed in California. However, she may have crafted her words carefully to avoid an outright denial of his condition during their two year separation, chronicling only her feelings of being “indignant and grieved” by statements suggesting Ulysses Grant was “dejected, low-spirited, badly-dressed and even slovenly.”

Finally, in August of 1854, he resigned from the U.S. Army and returned to his wife. Over the next four years, Grant farmed about sixty-acres of a hundred-acre property given him and Julia by her father as a wedding present, his primary income coming from selling cordwood. His wife insisted that Grant was “very successful” at farming, conceding only that it was “not as much as he anticipated from his calculations.” For her part, Julia Grant took charge of their large flock of chickens, yielding enough eggs and meat to keep their family well-fed. Although she was reluctant to ever detail the extent of the financial desperation of these years, her husband mentally suffered at the bleak future he foresaw for him and his family. While living in the home of her parents, Frederick Dent often openly belittled his son-in-law as a failure. Julia Grant and her mother, maintained great confidence in his future, both believing he would go on to greatness. In fact, Mrs. Grant remarked, “"But we will not always be in this condition. Wait until Dudy [her nickname for him at the time] becomes President." One observer at the time noted, "no man enjoyed a sweeter domestic felicity his supreme happiness centered in his home."

Although residing in a furnished Dent family house originally built for her brother Lewis, which the Grants dubbed “Wish-ton-wish,” it was a distance from the farm. Grant also built a log house which was nearer the fields, which the family dubbed “Hardscrabble” a reference to the seeming impossibility of surviving by farming. Mrs. Grant confessed to it being, “crude and homely,” and further confessed to falling into what she termed the “deepest despondency.” Again Julia Grant claimed that her ESP provided her with confidence of the family’s survival, calling out loud “Is this my destiny? These crude, not to say rough surroundings; to eat, to sleep, to wake again and again to the same.” To this, she continued, a “silvery light” above her, delivering the response that it was not her destiny, and to “be happy now.” She claimed that, despite even more financial crises ahead, she was never again to suffer from depression. She successfully argued against her father-in-law’s continued efforts to lure her husband into the tanning business in Kentucky because it would mean his separation from her and their children.

In desperation, Grant entered a real estate partnership with his wife’s cousin Harry Boggs in St. Louis, but failed at this occupation, often unable to appear on time for appointments and reluctant to press leasers for their rent.

Finally, in May of 1860, Ulysses and Julia Grant relocated to Galena, Illinois where he takes a position as clerk in his father’s tannery shop and the family moved into a small but comfortable house.

The circumstances were less than ideal for another reason. Grant’s father rigidly disapproved of what he considered to be the lavish and wasteful lifestyle of his daughter-in-law, and despite his relatively great wealth, he refused to provide them with anything but the most minimal and gratuitous of support.

As a woman, Julia Grant never received the right to vote, but did consider herself a political partisan. In the years leading up to the Civil War, she empathically stated, “I was a Democrat,” having been firmly inculcated by her father in the party’s foundational premise of states rights. At the time, she was not above arguing politics with Republican men she encountered in Galena, Illinois, defending the character of Kansas Territory Governor Samuel Medary. She became engaged in intellectual debate during the 1860 presidential election as the issue of secession arose, but soon developed a political ambivalence, led less by partisan loyalty and more by what she considered fair, believing in a state’s right to secede yet the necessity of the federal government to take action to prevent this. During the campaign, Ulysses Grant, she recalled, “read along to me every speech for and against secession.” As a woman, Julia Grant never received the right to vote, but did consider herself a political partisan. In the years leading up to the Civil War, she empathically stated, “I was a Democrat,” having been firmly inculcated by her father in the party’s foundational premise of states rights. At the time, she was not above arguing politics with Republican men she encountered in Galena, Illinois, defending the character of Kansas Territory Governor Samuel Medary. She became engaged in intellectual debate during the 1860 presidential election as the issue of secession arose, but soon developed a political ambivalence, led less by partisan loyalty and more by what she considered fair, believing in a state’s right to secede yet the necessity of the federal government to take action to prevent this. During the campaign, Ulysses Grant, she recalled, “read along to me every speech for and against secession.”

With the outbreak of the Civil War, Grant determined to return to active military service as an officer of the U.S. Army. While he was away, unsuccessful in his effort to meet with Union General George McClellan in pursuit of a commission, it was Julia Grant who opened his mail to discover that he had been reinstated as a colonel by the state of Illinois to return to the U.S. Army with the 21st Illinois infantry. Two months later, President Abraham Lincoln commissioned Grant as a Brigadier General.

The Civil War:

Role in Grant’s Military Career:

The marriage of Julia Dent and Ulysses Grant offers as unique a glimpse into the conflicts and challenges faced by couples of the mid-19th century who came from the two contrasting cultures of North and South. While similar in this respect to the union of Abraham and Mary Lincoln, the Grant marriage nevertheless provides a more dramatic context. Unlike Mary Lincoln who renounced her Confederate relatives, Julia Grant remained close to her slave-owning father and family members who supported the Confederacy. She did so at the very time that her husband was leading a war that accumulated an astronomical number of deaths to them as well as the Union Army that he led. Without apology for her family’s Confederate viewpoint, she was steadfast in her loyalty to her husband and the Union Army, a testament perhaps to her naturally diplomatic gifts. It was not a matter merely of shifting her remarks based on the views of people she encountered on either side of the conflict but her very presence in Union Army camps, to serve as ballast for her husband as he sought to remain emotionally steady through a rigorous sense of purposeful duty that was nevertheless traumatic.

In the initial phase of the Civil War, Julia Grant was uncertain about her role, feeling the need to volunteer with other Galena, Illinois women supporting the Union Army, but admitting to her lack of success when assigned to simply knit a pair of soldier socks in a week’s time.

Ultimately, Julia Grant’s most vital role during the Civil War was to provide a strong and constant flow of support to her husband. She did this by her physical presence with him at camp headquarters and, when apart, generating and replying to correspondence and taking actions such as making rental and financial arrangements, managing their property, and overseeing the education of their children. This provided General Grant with assurance of his fullest capacity for leadership and relief from anxiety over the well-being of his finances and family, permitting him to focus on his career and military tactics, as he rose through the ranks to head the Union Army and led it to victory.

Grant’s first military action as a Brigadier General occurred in November of 1861 at the Battle of Belmont, leading a raid on a Confederate encampment. Although his forces were forced to retreat, proved to be important to him as a lesson to trust his gift for military crucial experience for Grant, guiding his natural gift for military tactics. Julia Grant was not with him during this period but kept fully abreast of every battle move in a highly detailed letter from him. She would remain informed of the slightest movements of any military action in which he was involved, wisely determining not to depend merely upon his letters reporting his most recent moves, which could be long delayed or intercepted dependent not only through his initial. Subscribed to the St. Louis Democrat, however, Julia Grant was able to follow the military movement of her husband, the newspaper having a correspondent embedded in Grant’s brigade and reporting on his every movement.

Where she would remain based with their children during the war remained an issue subject to her access to her husband at base camp. Initially, she and the children briefly lived in Covington, Kentucky with his family, but then returned to their Galena, Illinois home.

As the war proceeded and Grant’s fame rose, the couple determined that Philadelphia would be safest place for them to consider a home base and ensure the continuity of their children’s educations; the matter of where they would live in that city was solved when wealthy members of the Philadelphia Union Club gave them an outright gift of a fully-furnished Chestnut Street home in that city, worth about $30,000. It not only spared the general’s wife the anxiety of finding and leasing a home but also proved to be a central asset in the family’s financial security. As the war proceeded and Grant’s fame rose, the couple determined that Philadelphia would be safest place for them to consider a home base and ensure the continuity of their children’s educations; the matter of where they would live in that city was solved when wealthy members of the Philadelphia Union Club gave them an outright gift of a fully-furnished Chestnut Street home in that city, worth about $30,000. It not only spared the general’s wife the anxiety of finding and leasing a home but also proved to be a central asset in the family’s financial security.

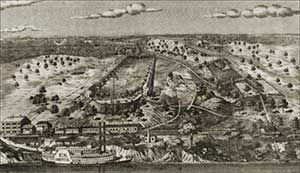

Grant proved his brilliance by leading a victory on Fort Donelson, Tennessee, the first Union Army strategic success. His actions at Fort Donelson thrust Grant into national headlines, as does his stated intention for how the war will end: “No terms except immediate and unconditional surrender.” As a result, Grant was given the rank of a two-star Major General.

Union Loyalty, Confederate Sympathy:

In a manner not dissimilar to what was experienced during the war by First Lady Mary Lincoln, a Kentucky native but First Lady of the Union, southern friends of Mrs. Grant verbally challenged the authenticity of her Union loyalty by revealing that they knew how to defy Union law and have their mail delivered to those living in the Confederacy, making it a dare for her to report it – which she did not. Her friendly trust of Confederate women she encountered in Mississippi, as well as her naïve decision to travel with one of her slaves and permit herself to be exposed to their negative anti-Union songs, seemed to only give credence to their charge that Mrs. Grant was with the Confederacy “in feeling and principle.”

From the moment he decided to enter the army as a matter of principled conviction that the southern states had no right to secede from the United States, her support was firm. "Julia takes a very sensible view of the present difficulties,” Grant wrote to his father at the time, “She would be sorry to have me go, but thinks the circumstances may warrant it and will not throw a single obstacle in the way."

Julia Grant held to this conviction knowing that it could irreparably damage her intensely close relationship with her father. Grant wrote to Colonel Dent, rationally explaining his decision to side with the Union, stating plainly that, “now is the time, particularly in the border slave states for men to prove their love of country. I know it is hard for men to apparently work with the Republican Party but now all party distinctions should be lost sight of, and every true patriot be for maintaining the integrity of the glorious old Stars and Stripes, the Constitution and the Union. the Southerners have been the aggressors.”

Her father, however, conceded nothing on the matter, badgering Grant that he could much more easily enter the fray with higher military rank if he joined the Confederate Army. Grant refused, so enraging Fred Dent that he sharply retorted, "Send Julia and the children here. As you make your bed so you must lie." It was a testament to the couple’s commitment to each other that they never wavered, though the loss of previously close family relationships was devastating. "If you are with the accursed Lincolnites,” one of Grant’s aunts wrote them, “the ties of consanguinity shall be forever severed." Her father, however, conceded nothing on the matter, badgering Grant that he could much more easily enter the fray with higher military rank if he joined the Confederate Army. Grant refused, so enraging Fred Dent that he sharply retorted, "Send Julia and the children here. As you make your bed so you must lie." It was a testament to the couple’s commitment to each other that they never wavered, though the loss of previously close family relationships was devastating. "If you are with the accursed Lincolnites,” one of Grant’s aunts wrote them, “the ties of consanguinity shall be forever severed."

It was a tribute to Mrs. Grant’s considerable exercise of charm that she was able to maintain her absolute loyalty to her husband during the Civil War while avoiding an outright breach with her father. Other family members of both of the Grants declared themselves permanently estranged from the couple because of their Union loyalty. Whenever Unionists verbally attacked the South in her presence, Julia Grant disciplined herself to remain silent.

Slavery:

It is unclear whether the African American servants who continued to work for Julia Grant throughout the Civil War had been given their freedom and were being paid or whether they were still held in bondage. The Emancipation Proclamation exempted the state of Missouri where they had been originally registered as her property. Grant scholar John Y. Simon believed that Mrs. Grant continued to hold as >personal property the four slaves she had been given by her father, identified only by their first names of Eliza, Dan, Julia and John as property until they were granted their freedom by passage of the 13th Amendment in 1865. Although they would be legally granted immediate freedom while residing in residents in the Galena, Illinois of the Grants, none of the four slaves sought to break from the family.

During her initial stays at her husband’s headquarters, Mrs. Grant ‘s slave, named Julia, accompanied her; they worked alongside each other as nurses in Union Army hospitals. Mrs. Grant’s father, however, had warned her that doing this would mean that anywhere within Union-held territory, her slaves would be considered free and that she risked losing the free labor she depended upon by doing this.  Ignoring his advice, Mrs. Grant experienced precisely what he’d predicted when her enslaved companion Julia ran for freedom and escaped, in Union-held Jackson, Mississippi. Ignoring his advice, Mrs. Grant experienced precisely what he’d predicted when her enslaved companion Julia ran for freedom and escaped, in Union-held Jackson, Mississippi.

For General Grant, leading a military force which, at its widest intent, also sought to eradicate slavery after the Emancipation Proclamation was enacted, his wife’s loss was actually a relief of what was becoming not only a moral dilemma for him, but overt hypocrisy. For her part, however, Julia Grant never did express remorse for holding human beings as property.

In Camp:

Longing for her presence at his side, Grant initially considered having Julia join him at camp in Kentucky, in September of 1861. As with all his decisions regarding her wartime movement, however, he refused to indulge his compulsion to be with her when safety was a factor. Her first presence in camp took place at the end of November of 1861, at Cairo, Illinois, broken only by a brief but trying visit back to her father in St. Louis. She remained at Cairo until the end of January of 1862, after which she moved with her children to the Covington home of her in-laws.

In the spring of 1862, following the Battle of Shiloh, Julia Grant again returned to her husband’s base camp, this time in Corinth, bringing along all of their children. She repeatedly settled, then picked up again, depending on the movement of his headquarters, making a home in any livable space, be it an inn, a confiscated Confederate home, a log barrack or a canvas tent.

After a retreat to the senior Grant home in Covington, she returned to join Ulysses in October of 1862 at Jackson, Mississippi. While here, her enslaved woman servant Julia escaped, running to freedom. General Grant was, in fact, pleased about this, a relative recalling that he "wanted to give his wife's slaves their freedom as soon as he was able." After a retreat to the senior Grant home in Covington, she returned to join Ulysses in October of 1862 at Jackson, Mississippi. While here, her enslaved woman servant Julia escaped, running to freedom. General Grant was, in fact, pleased about this, a relative recalling that he "wanted to give his wife's slaves their freedom as soon as he was able."

Grant did specifically locate his headquarters at Nashville, Tennessee following the Battle of Vicksburg, so that Julia Grant could come live with him there in relative comfort. The day she arrived, however, he was away and didn’t return for many hours. With “a great deal of sorrow” he then informed her that he had to immediately go to the war front and would thus be unable to live there with her for five long days. His leaving upon her immediate arrival provoked gossip among Confederate women, suggesting that it was Julia Grant who had insisted upon being with her husband, provoking him to flee. Both were amused, rather than insulted by this, Grant telling her to point out that he had “put my headquarters here just on purpose to have you with me.”

It was always in response to General Grant’s imploring that his wife came to him, and always for a period and at a base camp that he determined was relatively safe. Even if he foresaw that a chance for their reunion would only prove brief, he implored her to join him. “I do not know what I may be called on for next, supposing that I am successful here, “ her wrote her in 1863 from Mississippi before the Battle of Vicksburg,” but you can at least join me until I am compelled to go elsewhere.”

Never seeking to conceal her identity and increasingly recognizable due to public distribution of her photograph on the era’s popular carte-de-visite cards, Julia Grant was always susceptible to capture or harm by Confederates.

After joining her husband at Memphis, Tennessee in July of 1862, and then proceeding with him to Corinth, Mississippi, where she remained for a month, she was an easy target in the South. In August, she was stationary for a length of time at Grant’s secondary, supply base camp at Holly Springs, Mississippi, headquartered in the private home of a Confederate family by the name of Walters, which had been seized by Union troops. When Confederate General Earl Van Dorn led a surprise attack on the Union supply camp there, his troops confiscated Mrs. Grant’s horses and burned her carriage although her personal belongings were protected by the wife of captured Confederate soldier Pugh Govan; in gratitude for this, Julia Grant interceded to obtain the release of Govan from a Union prison and her husband issued an order protecting the Walters home from Union Army destruction or raid. It is unclear whether she was present during the raid: some family members claimed she was there, an account conflicting with one left by a Confederate soldier under Van Dorn’s command.

The presence in a war camp of a general’s wife was an unusual decision and did not escape some private disapproval by some of his military staff. Among these, the most important was his aide-de-camp General John A. Rawlins. Eventually he not only became reconciled to her presence in camp but he came to form a strong alliance with her in their joint effort to protect the reputation and career of Grant. She was often even present even during military strategy sessions. Once, cognizant of the confidential maneuvers being discussed by her husband and General John Sherman, she quipped, "Perhaps you don't want me here listening to your secrets?” Trusting her confidence, Sherman nonetheless teased, "Do you think we can trust her, Grant?" to which her husband quipped, "I'm not so sure about that.” After posing a mock-serious battery of military questions, Sherman replied, "Well, Grant, I think we can trust her."

It was also the general who urged his wife to bring their family to live with him whenever it was deemed reasonably safe and at one point his eldest son Fred, then twelve, lived with him in camp during the 1863 battle of Vicksburg. The young man teenager not only witnessed fighting but was grazed by a bullet. As word of the presence of the Grant children in camp went beyond the circle of the Union Army to the general population, each of the children also began to develop a public profile. The dark side was that it made them targets for Confederate kidnapping. One such attempted incident was prevented only when Julia’s sister Emma acted swiftly to relocate her nephew Fred from two strangers asking about his whereabouts.

Growing Fame:

Julia Grant was more pro-active than her husband when it came to the growing press interest in him as an individual, spouse and father. Grant’s rapid rise through military ranks, surpassing many of his compatriots, also led to the revival and circulation of stories about his “former bad habits” of heavy drinking during his desolate years of isolated assignment in California. A kernel of truth was apparently enough for those jealous of his sudden prominence to embellish tales of his alcohol consumption and its resulting affect on him.

From that point on, until her own death, Julia Grant denied outright that her husband had ever consumed alcohol in any excessive amount. Whether she emphatically stated this for the record knowing it to be the truth, knowing it to be an outright lie or was never fully informed of the fullest extent of his drinking or simply never witnessed him in any suggestion of even its partial truth is unknown. In their post-White House years, while in England, there was an eyewitness account that claimed that Grant had become ill from excessive alcohol consumption and did so in his wife’s presence. From that point on, until her own death, Julia Grant denied outright that her husband had ever consumed alcohol in any excessive amount. Whether she emphatically stated this for the record knowing it to be the truth, knowing it to be an outright lie or was never fully informed of the fullest extent of his drinking or simply never witnessed him in any suggestion of even its partial truth is unknown. In their post-White House years, while in England, there was an eyewitness account that claimed that Grant had become ill from excessive alcohol consumption and did so in his wife’s presence.

Julia Grant’s blanket denial of her husband drinking, however, is the most dramatic example of her genuine belief that he was honest in all his interactions and right in all his decisions, a factor that ultimately proved vital to his confident success as leader of the Union Army leading to military victory over the Confederacy.

As the war went on, Julia Grant wasn’t just concerned with the public image of her husband but that of her own as well. Sensitive to the fact that she her eyes were crossed she began to pose only from a side view for photographs intended for public distribution.

Her photograph, taken in studios was also soon being sold and distributed to the public, sometimes being superimposed with her famous husband. Mrs. Grant never discouraged stories about her husband, herself and their family life. Consequently, by war’s end the American public had a general idea of not just Ulysses and Julia Grant as individuals but their children Fred, Buck, Nellie and Jesse; this was unprecedented for any military figure to that time. Her photograph, taken in studios was also soon being sold and distributed to the public, sometimes being superimposed with her famous husband. Mrs. Grant never discouraged stories about her husband, herself and their family life. Consequently, by war’s end the American public had a general idea of not just Ulysses and Julia Grant as individuals but their children Fred, Buck, Nellie and Jesse; this was unprecedented for any military figure to that time.

Financial Management:

Living as head of her own household also trained Julia Grant in real estate management and transactions. Following the explicit directions on specific prices, acreage and contractual details on land development which Ulysses sent to her, Mrs. Grant oversaw the rental agreements on portions of the White Haven, Missouri property which the couple had, by then, purchased from her father. She also learned to negotiate in successfully collecting on debts owed to her husband.

Influence on Military Matters:

Not wanting to remain idle, Julia Grant immediately joined Confederate women and volunteered as a hospital nurse. Interacting with wounded men from both the Union and Confederate armies, her unfiltered empathy soon enough made her the recipient of requests from people both known and unknown to her, asking her to influence the general into appointing them to various support positions in, or sub-contract offered services to the Union Army. Following her husband’s lead, she refused to entertain these pleas. She adopted a different attitude, however, when it came to interceding on behalf of soldiers or their families from both the Union and Confederate armies who made simple requests that appealed to her. On another occasion, Mrs. Grant successfully interceded on behalf of a soldier convicted of desertion to be punished by hanging. His wife, a new mother who’d convinced her enlisted husband to abandon his post to see the child, came directly to Julia Grant in her camp quarters. She gave entrée to the young woman who directly appealed to General Grant, resulting in the man’s pardon.

The letters he penned Julia Grant from the front were not, she recalled, full of important historical content but rather focused on personal and family matters. She recalled: “The General never talked war matters with me at all. He wrote very little about the war, even after the taking of Vicksburg. I don’t remember that he wrote me any letter of exultation or joy. He was so sorry for the poor fellows who were opposed to him that he could never exult over any victory. He always felt relieved, of course, and glad that it seemed to promise to shorten the war, but he never exulted over them.”

Relationship with Mary Lincoln

Certainly with pride and perhaps with a farsighted ambition for her long-held belief her husband would become President, towards the end of the war, Julia Grant implored her husband to invite the President and Mrs. Lincoln to visit him at his Virginia encampment at City Point. Ignoring his belief that, as commander-in-chief, Lincoln would tour any military installation he wished to, she discovered from First Son Robert Lincoln, then serving as a captain to General Grant, that his parents welcomed an invitation, which they soon received and accepted.

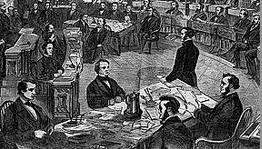

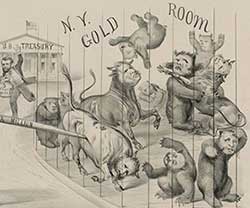

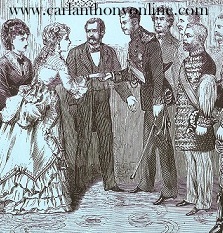

At the time, the public knew little about the tensions that developed between Julia Grant and Mary Lincoln. As the central image of a popular drawing of the “Grand Reception” at the White House on the occasion of Lincoln’s March 1865 second Inauguration, Julia Grant was shown smiling as she shakes hands with the President and the First Lady. At the time, the public knew little about the tensions that developed between Julia Grant and Mary Lincoln. As the central image of a popular drawing of the “Grand Reception” at the White House on the occasion of Lincoln’s March 1865 second Inauguration, Julia Grant was shown smiling as she shakes hands with the President and the First Lady.

Much lore exists about what amounts to a feud in the closing months of the Civil War between First Lady Mary Lincoln and the General’s wife Julia Grant. Their initial meeting took place at Grant’s City Point, Virginia headquarters in March of 1865, when the President and his wife arrived for an inspection tour and stay there.

Rather than express gratitude to Mrs. Grant for encouraging the Lincoln visit, the First Lady was put off by her presence, remarking that she “thought ladies were not allowed in camp.” To this, Mrs. Grant smilingly replied, “General Grant is much opposed to their being present, but when I wanted to come I wrote him a nice, coaxing letter, and permission was always granted.” Mrs. Lincoln, however, was not amused by this.

Shortly after, Mrs. Grant came to call, seating herself next to Mary Lincoln on a coach, which provoked the latter to snap, “How dare you?” In recalling the incident, Mrs. Grant’s sister later claimed that the general’s wife, outraged at such rudeness, walked out.

When both women were driven to the front after battle, to join their husbands, Grant aides Horace Porter and Adam Badeau were eyewitness to the women’s interactions. Badeau mentioned to them that due to reports of continued skirmishes it was thought wiser that all women be sent into retreat and that General Charles Griffin’s wife had sought and received permission from the President to move forward. This sent Mrs. Lincoln into a rage, yelling, “What do you mean by that, sir? Do you mean to say that she saw the President alone? Do you know that I never allow the President to see any woman alone?" She then insisted, "I will ask the President if he saw that woman alone," and ordered the coachman to halt. Horrified at this behavior, Julia Grant gingerly attempted to calm her, later instructing the aide to keep the incident to himself.

When later, Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Grant were delayed as they were being transported to join the President and the General at a military review, Sally Ord, the attractive wife of another general, alone on horseback, was told not to wait for the other women but rather to join the President, also on horseback, who had begun the review without waiting for his wife and Mrs. Grant. When the vehicle with the two women finally approached within sight of the review, Mrs. Lincoln was livid, yelling at an aide, "What does the woman mean by riding by the side of the President and ahead of me? Does she suppose that he wants her by the side of him?” She then turned on Mrs. Ord. According to Grant’s aide Adam Badeau, the First Lady "positively insulted her…[with] vile names in the presence of a crowd of officers, and asked what she meant by following up the President."

Mrs. Ord burst out crying, prompting Julia Grant to defend her. This then provoked Mary Lincoln to verbally assault Julia Grant: "I suppose you think you'll get to the White House yourself, don't you?"

Julia Grant remained calm, remarking that she was happy with her lot in life, and it was a greater status than she’d ever imagined she would attain. This only further angered Mary Lincoln, who finally snapped, "Oh! You had better take it if you can get it. ? Tis very nice."

There was at least one other known encounter between the two women. When an aide invited by Robert Lincoln onto the River Queen, the official vessel being used by the President and his wife lingered with Julia Grant in an inner cabin, she noticed Mrs. Lincoln standing alone by herself on the deck, and urged him to fetch a chair for the First Lady. When he approached her politely with the chair, she sharply dismissed him, and then called Mrs. Grant to her side. This encounter was apparently friendly enough, but the First Lady asked Mrs. Grant to have the aide removed from the River Queen. Further, Mrs. Lincoln insisted that her boat must always be closest to the shore and would not cross over the Grant vessel, The Martin, to walk to land. There was at least one other known encounter between the two women. When an aide invited by Robert Lincoln onto the River Queen, the official vessel being used by the President and his wife lingered with Julia Grant in an inner cabin, she noticed Mrs. Lincoln standing alone by herself on the deck, and urged him to fetch a chair for the First Lady. When he approached her politely with the chair, she sharply dismissed him, and then called Mrs. Grant to her side. This encounter was apparently friendly enough, but the First Lady asked Mrs. Grant to have the aide removed from the River Queen. Further, Mrs. Lincoln insisted that her boat must always be closest to the shore and would not cross over the Grant vessel, The Martin, to walk to land.

It has been speculated that the “feud” was less about personal animosity between the two women and rooted more in Mary Lincoln’s initial judgment of Grant as a “butcher,” and Julia Grant’s resentment of that sentiment. There is also some indication that she held an ultimately sympathetic if removed perspective on Mrs. Lincoln and the emotional instability, which the Civil War had created for her.

End of the Civil War:

Towards the end of the war, Julia Grant’s national profile had become prominent enough that she was even briefly considered for a type of prelude role to the negotiation of a peace treaty. Union general Edward Ord raised the idea of an exchange of two social calls, one behind Confederate lines, the other behind Union lines between Julia Grant and her old friend Louise Longstreet, who also happened to be the wife of a Confederate general. While these two visits were being made, it was suggested, Grant and Confederate general Robert E. Lee would be encouraged to simultaneously negotiate the peace treaty in complete trust, helping ensure that “terms honorable to both sides could be found.” The plan fell through and robbed Mrs. Grant, she felt, from a role in helping end the war. Towards the end of the war, Julia Grant’s national profile had become prominent enough that she was even briefly considered for a type of prelude role to the negotiation of a peace treaty. Union general Edward Ord raised the idea of an exchange of two social calls, one behind Confederate lines, the other behind Union lines between Julia Grant and her old friend Louise Longstreet, who also happened to be the wife of a Confederate general. While these two visits were being made, it was suggested, Grant and Confederate general Robert E. Lee would be encouraged to simultaneously negotiate the peace treaty in complete trust, helping ensure that “terms honorable to both sides could be found.” The plan fell through and robbed Mrs. Grant, she felt, from a role in helping end the war.

Julia Grant’s longest unbroken period of living with her husband at a military headquarters was at City Point, Virginia from June of 1864 to April of 1865 during the Petersburg siege. Having learned that General Robert E. Lee had surrendered to her husband while she was aboard a Union vessel in the James River, Virginia, Julia Grant remained awake as long as she could in anticipation of his return, overseeing the preparation of a victory dinner. Finally falling asleep, he returned to awake her, confirming the news of the war’s end and they celebrated by sharing the dinner meal as breakfast.

The Lincoln Assassination

Given her unpleasant history with Mrs. Lincoln, Julia Grant was loathe to be with her again, especially at large events where the public would observe their interactions. Another insult came when the Lincolns invited General Grant to a grand White House celebration of the war’s end on April 13, 1865, but not Mrs. Grant. He refused to attend. The following day, Mrs. Lincoln did invite Mrs. Grant with her husband to join her and the President for a Ford’s Theater performance of Our American Cousins. Given her unpleasant history with Mrs. Lincoln, Julia Grant was loathe to be with her again, especially at large events where the public would observe their interactions. Another insult came when the Lincolns invited General Grant to a grand White House celebration of the war’s end on April 13, 1865, but not Mrs. Grant. He refused to attend. The following day, Mrs. Lincoln did invite Mrs. Grant with her husband to join her and the President for a Ford’s Theater performance of Our American Cousins.

Julia Grant gave her husband the right to accept but otherwise told him, “I will not sit without you in the box with Mrs. Lincoln." The couple used the honest excuse of wanting to be reunited with their children, then staying in their Burlington, New Jersey home.

However, several other factors seem likely to have contributed to their refusal to join the Lincolns at the theater. Mrs. Grant recounted that an ominous-looking man on horseback had apparently been following her open carriage and stared in on her earlier that day, leaving her frightened. According to her sister, she had also had one of her premonitory dream about danger that night. However, several other factors seem likely to have contributed to their refusal to join the Lincolns at the theater. Mrs. Grant recounted that an ominous-looking man on horseback had apparently been following her open carriage and stared in on her earlier that day, leaving her frightened. According to her sister, she had also had one of her premonitory dream about danger that night.

While Julia Grant has often been credited with saving the life of her husband, whose name had appeared on the hit list of the assassination conspirators, General Grant essentially suggested that her decision may have unwittingly cost the life of Lincoln, for had they attended his strong cordon of military guards would have been in attendance and prevented Lincoln’s death. The Grants left Washington that evening by railroad, learning at the stop in Philadelphia that the President had been shot.

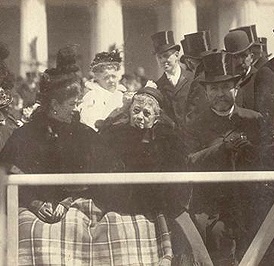

Post-Civil War Life

Julia Grant did not join her husband in Washington for Lincoln’s state funeral. She was, however, a prominent figure in the reviewing stand in front of the White House for the two days of massive victory parades in Washington on May 23 and 24, 1865. Julia Grant did not join her husband in Washington for Lincoln’s state funeral. She was, however, a prominent figure in the reviewing stand in front of the White House for the two days of massive victory parades in Washington on May 23 and 24, 1865.

Although her husband was embarrassed at the lavish public outpouring that heralded him as the nation’s greatest hero, in gratitude for the perception that he seemingly ended the Civil War single-handedly, Julia Grant insisted that it was his due, and reveled in seeing him made a hero. She made an effort not only to share in his glorious post-war honors but insisted that their children also be included at every possible reception where their father was being heralded.

During the summer of 1865, Julia Grant travelled with the General during his rail tour of northern cities, where he was honored with endless parades, receptions and large dinner banquets, both of them plied with gifts from the grateful public. During the summer of 1865, Julia Grant travelled with the General during his rail tour of northern cities, where he was honored with endless parades, receptions and large dinner banquets, both of them plied with gifts from the grateful public.

When the Grant family arrived back in Galena, Illinois, a crowd estimated at 10,000 hailed them. The local residents presented them with a furnished brick home. The family made use of the Galena property as a real home in the postwar years, if only on an intermitted basis.

Julia Grant welcomed newspaper correspondents into the house to see her family enjoying the rooms of the home, even permitting them to sketch them in private moments like their dinner meal or gathering in the parlor. Julia Grant welcomed newspaper correspondents into the house to see her family enjoying the rooms of the home, even permitting them to sketch them in private moments like their dinner meal or gathering in the parlor.

Grant’s ongoing work with the War Department and his subsequent appointment by President Andrew Johnson as Acting Secretary of War in Washington required his presence in Washington, D.C.

After enduring constant separation from his family during the war, he would no longer tolerate this and thus the family decided not to make Galena their primary residence but to rather relocate to Washington during the initial Reconstruction era.

Ultimately, it proved more practical for them to live in Washington, first in the Georgetown section and then, by the end of 1865, in a large rowhouse at 2025 I Street, Northwest. Ultimately, it proved more practical for them to live in Washington, first in the Georgetown section and then, by the end of 1865, in a large rowhouse at 2025 I Street, Northwest.

View of President Andrew Johnson and his family

Unstated but implicit in her views, Julia Grant’s political views during Reconstruction may have influenced her friendly relationship with President Johnson and his family. Given her southern acculturation, Julia Grant was in favor of a tolerant and forgiving attitude towards former Confederates, a policy of President Johnson that led to political challenges of his power. With this, her husband was in accord, writing her on April 25, 1865 that, "people who talked of further retaliation and punishment, except of the political leaders, either do not conceive of the suffering endured already or they are heartless and unfeeling."

Despite the fact that Grant was aware of the fact that President Johnson was using his popularity in an attempt to shield himself from criticism of being too lenient in Reconstruction policy, Julia Grant maintained a friendly relationship with him. On at least one occasion, President Johnson honored her by coming to a reception in their private home, an uncommon custom then for an incumbent Chief Executive.

In later years, Julia Grant praised the manners and appearance of the primary public hostess of the Administration, the President’s married daughter Martha Johnson Patterson. None of the Johnson family seemed to flinch when the Marine Band struck up “Hail to the Chief,” the song usually reserved for the President when the Grants entered the White House for the 1866 New Year’s Day Reception. Julia Grant, however, did not join her husband and Martha Patterson on President Johnson’s disastrous public railroad tour in the summer of 1866. In later years, Julia Grant praised the manners and appearance of the primary public hostess of the Administration, the President’s married daughter Martha Johnson Patterson. None of the Johnson family seemed to flinch when the Marine Band struck up “Hail to the Chief,” the song usually reserved for the President when the Grants entered the White House for the 1866 New Year’s Day Reception. Julia Grant, however, did not join her husband and Martha Patterson on President Johnson’s disastrous public railroad tour in the summer of 1866.

By virtue of her husband’s fame, Julia Grant became an overnight sensation in Washington, the general public pushing their way into what she intended to be private receptions in her home. A lavish hostess, invitations to dine in Grant home were a prized commodity among the city’s political elite. Around the city, she was always considered the most prominent figure in the audience at the many lectures, concerts, sermons and theatrical productions she attended. Beyond the circle of military figures of high rank, she came to know key Republican figures in the House and Senate and also befriended many members of the diplomatic corps.

Julia Grant actually provides one of the few first-hand accounts of Eliza Johnson’s presence at formal White House social events, belying the popular misconception that the First Lady was never seen in public. Given the acrimony that developed between President Johnson and General Grant and Julia Grant’s fervent defense of any questionable action or behavior of her husband, her warm recollections of Mrs. Johnson are noteworthy. Archival inventories, however, indicate no direct correspondence between Julia Grant and any of the Johnson family. Julia Grant actually provides one of the few first-hand accounts of Eliza Johnson’s presence at formal White House social events, belying the popular misconception that the First Lady was never seen in public. Given the acrimony that developed between President Johnson and General Grant and Julia Grant’s fervent defense of any questionable action or behavior of her husband, her warm recollections of Mrs. Johnson are noteworthy. Archival inventories, however, indicate no direct correspondence between Julia Grant and any of the Johnson family.

Campaign and Inauguration:

Believing it was her husband’s destiny to become President of the United States, Julia Grant never doubted that, once nominated by the Republican Party as their presidential candidate in 1868, he would win. The candidate did not openly campaign as in later generations, but delegations and individuals came to Grant’s home in Galena to meet him; there Mrs. Grant opened their home, serving refreshments.

On Election night 1868, Julia Grant remained home alone while her husband went to visit friends and play a game of cards, awaiting the returns. When it was clear that her husband had won the presidency, he returned home to s imply tell her, “I am afraid I am elected.” Julia Grant joined him at the door of their Galena home in the morning hours after Election Day, to acknowledge a crowd of supporters who had gathered there to salute him. imply tell her, “I am afraid I am elected.” Julia Grant joined him at the door of their Galena home in the morning hours after Election Day, to acknowledge a crowd of supporters who had gathered there to salute him.

Concerned about the content of his March 4, 1869 Inaugural Address, Julia Grant urged her husband to consult the rather facile Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York, upon finishing his speech, the new President turned to shake the hand of the new First Lady, quipping, "And now, my dear, I hope you're satisfied.” Following the ceremony, Chief Justice Salmon Chase presented Julia Grant with the Bible on which her husband had sworn his oath of office. Standing during the ceremony, she had her elderly father seated near her, despite his continued opposition to Grant’s politics. She would insist upon the now-infirm Colonel Dent live with her and her family in the White House.

The 1869 Inaugural Ball, held in a wing of the Treasury Department which had been rapidly been completed for the event, proved disastrous with building dust still in the air, debris in the hallways, overcrowding and insufficient staff to handle the coat check. In her gown of white satin and lace, and wearing diamonds and pearls, the new First Lady was a figure of interest equal to her husband, sought out by celebrity guests including Horace Greeley, General Sherman and poet Julia Ward Howe. The 1869 Inaugural Ball, held in a wing of the Treasury Department which had been rapidly been completed for the event, proved disastrous with building dust still in the air, debris in the hallways, overcrowding and insufficient staff to handle the coat check. In her gown of white satin and lace, and wearing diamonds and pearls, the new First Lady was a figure of interest equal to her husband, sought out by celebrity guests including Horace Greeley, General Sherman and poet Julia Ward Howe.

First Lady:

4 March 1869 – 4 March 1877

43 years old

How She Perceived Being First Lady

Julia Grant recalled her eight years as First Lady with the same lavishly romanticized metaphor of a flourishing garden of delights that she used in remembering her childhood. It was not merely the privilege of living in the Executive Mansion and its inherent right to decorate the public rooms and entertain at formal functions, but also the adulation she received personally when she made public appearances, a role she especially relished. Although press and public acknowledgement that women married to or serving as an official hostess to an President held a unique, national status began with Martha Washington at the presidency’s inception, few of the previous women so entirely embraced this as did Julia Grant and none for as long a period. There was also novelty for the public in having a president’s wife solely assume the First Lady role for eight consecutive years; the last time such a situation has occurred was over a half a century earlier when Dolley Madison ended her White House tenure in 1817.