|

Copyright, Attention: This website and its contents contain intellectual property copyright materials and works belonging to the National First Ladies’ Library and Historic Site and to other third parties. Please do not plagiarize. If you use a direct quote from our website please cite your reference and provide a link back to the source.

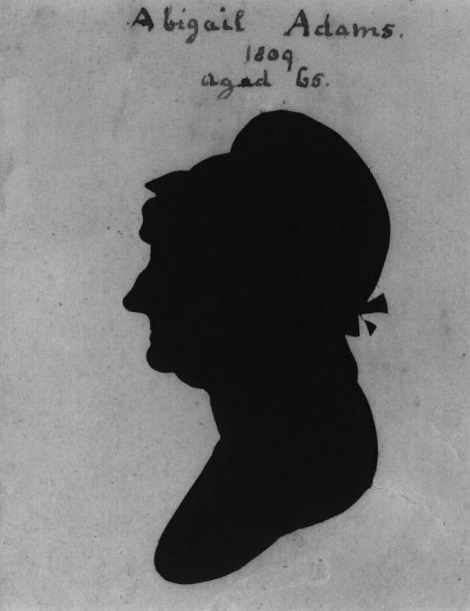

First Lady Biography: Abigail Adams

ABIGAIL SMITH ADAMS

Born:

Place: Weymouth, Massachusetts

Date: 1744, November 11

Father:

William Smith, 1706, January 29, Charlestown, Massachusetts, died 1783, September, Weymouth, Massachusetts. He was a Congregationalist minister.

Mother:

Elizabeth Quincy, born 1721, Braintree, Massachusetts, died 1775, Weymouth, Massachusetts; married in 1740. She was the daughter of John Quincy, a member of the colonial Governor's council and colonel of the militia. Mr. Quincy was also Speaker of the Massachusetts Assembly, a post he held for 40 years until his death at age 77. He died in 1767; three years into his granddaughter Abigail Smith's marriage to John Adams, and his interest in government

and his career in public service influenced her.

and his career in public service influenced her.

Ancestry:

English, Welsh; Abigail Adams' paternal great-grandfather, Thomas Smith, was born 1645, May 10, and immigrated to Charleston, Massachusetts from Dartmouth, England. One of her great-great-great-great grandmothers came from a Welsh family. Her well-researched ancestral roots precede her birth some six centuries and are traced back to royal lines in France, Germany, Belgium, Hungary, Holland, Spain, Italy, Ireland and Switzerland.

Birth Order and Siblings:

Second born; one brother, three sisters, Mary Smith Cranch (1741-1811), William Smith (1746-1787), Elizabeth Smith Shaw Peabody (1750-1815)

Physical Appearance:

5' 1", brown hair, brown eyes

Religious Affiliation:

Congregationalist; she was buried in the Unitarian faith of her husband.

Education:

Although Abigail Adams was later known for advocating an education in the public schools for girls that was equal to that given to boys, she herself had no formal education. She was taught to read and write at home, and given access to the extensive libraries of her father and maternal grandfather, taking a special interest in philosophy, theology, Shakespeare, the classics, ancient history, government and law.

Occupation before Marriage:

No documentation exists to suggest any involvement of Abigail Adams as a young woman in her father's parsonage activities. She recalled that in her earliest years, she was often in poor health. Reading and corresponding with family and friends occupied most of her time as a young woman. She did not play cards, sing or dance.

Marriage:

19 years old, married 1764, October 25 to John Adams, lawyer (1735-1826), in Smith family home, Weymouth, Massachusetts, wed in matrimony by her father, the Reverend Smith. After the ceremony, they drove in a horse and carriage to a cottage that stood beside the one where John Adams had been born and raised. This became their first home. They moved to Boston in a series of rented homes before buying a large farm, "Peacefield," in 1787, while John Adams was Minister to Great Britain.

Children: Children:

Three sons and two daughters;

Abigail " Nabby " Amelia Adams Smith

(1765–1813),

John Quincy Adams (1767–1848), Susanna Adams (1768–1770), Charles Adams (1770–1800), Thomas Boylston Adams (1772–1832)

Occupation after Marriage:

Abigail Adams gave birth to her first child ten days shy of nine months after her marriage, thus working almost immediately as a mother. She also shared with her husband the management of the household finances and the farming of their property for sustenance, while he also practiced law in the nearby city of Boston.

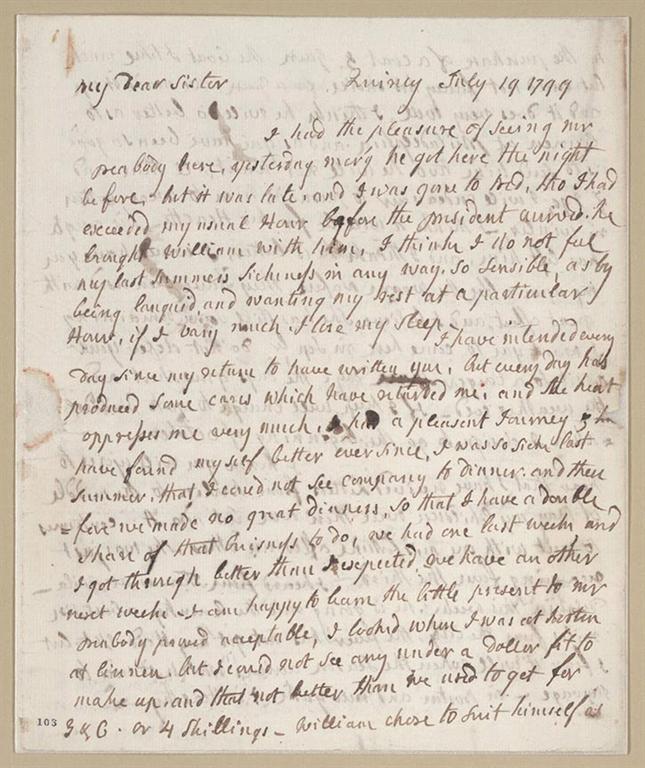

When John Adams went to Philadelphia in 1774 to serve as his colony's delegate to the First Continental Congress, Abigail Adams remained home. The separation prompted the start of a lifelong correspondence between them, forming not only a rich archive that reflected the evolution of a marriage of the Revolutionary and Federal eras, but a chronology of the public issues debated and confronted by the new nation's leaders. The letters reflect not only Abigail Adams' reactive advice to the political contentions and questions that John posed to her, but also her own observant reporting of New England newspapers' and citizens' response to legislation and news events of the American Revolution.

As the colonial fight for independence from the mother country ensued, Abigail Adams was appointed by the Massachusetts Colony General Court in 1775, along with Mercy Warren and the governor's wife Hannah Winthrop to question their fellow Massachusetts women who were charged by their word or action of remaining loyal to the British crown and working against the independence movement. "…you are now a politician and now elected into an important office, that of judges of Tory ladies, which will give you, naturally, an influence with your sex," her husband wrote her in response to the appointment. This was the first instance of a First Lady who held any quasi-official government position.

As the Second Continental Congress drew up and debated the Declaration of Independence through 1776, Abigail Adams began to press the argument in letters to her husband that the creation of a new form of government was an opportunity to make equitable the legal status of women to that of men. Despite her inability to convince him of this, the text of those letters became some of the earliest known writings calling for women's equal rights.

Separated from her husband when he left for his diplomatic service as minister to France, and then to England in 1778, she kept him informed of domestic politics while he confided international affairs to her. She joined him in 1783, exploring France and England, received in the latter nation by the king. Upon their return, during John Adams' tenure as the first Vice President (1789-1797), Abigail Adams spent part of the year in the capital cities of New York and Philadelphia, while Congress was in session.

Presidential Campaign and Inauguration:

Presidential Campaign and Inauguration:

As much of her political role was conducted in correspondence, so too was Abigail Adams's active interest in her husband's two presidential campaigns, in 1796 and 1800, when his primary challenger was their close friend, anti-Federalist Thomas Jefferson. Caring for her husband's dying mother Abigail Adams was unable to attend his March 4, 1797 inaugural ceremony in Philadelphia. She was highly conscious, however, of how their lives would change that day, with "a sense of the obligations, the important trusts, and numerous duties connected with it . " Although she relished a good political conversation, she increasing found it a profession beset by “envy, hatred, malice, and all uncharitableness" in all three branches of government.

Her caution about their old friend Thomas Jefferson had grown to mistrust by this point, he having come in second in the presidential election campaign against her husband and, in the old system, was thus declared the new Vice President. She heard a rumor that Jefferson’s close friend James Madison had been appointed as Minister to France by outgoing President George Washington ( false rumor ) and said she thought Madison was a man of integrity when it came to his principals but questioned those principals.

Knowing that her every word, be it written or spoken, would be examined, criticized, ridiculed and used against the new Administration, she caught herself in the middle of writing one political missive.“ My pen runs riot, ” Abigail Adams fearfully concluded the letter to her husband. “ I forget that it must grow cautious and prudent. I fear I shall make a dull business when such restrictions are laid upon it. ”

Not long after Adams had been elected, Mrs. Adams even compared the prospect of becoming First Lady to being “fastened up hand and foot and tongue to be shot at as our Quincy lads do at the poor geese and turkies.” She elaborated further, in another letter at the time: “ I have been so used to freedom of sentiment that I know not how to place so many guards about me, as will be indispensable, to look at every word before I utter it, and to impose a silence upon myself, when I long to talk.”

“ I expect to be vilified and abused, ” Mrs. Adams admitted in still another letter. “ When I come into this situation…” When her friend and fellow feminist Mercy Otis Warren wrote to Abigail Adams congratulating her on being thrust into “ this elevated position ” as the most politically prominent woman in the United States, the new First Lady responded on the day her husband became president that, “ I shall esteem myself peculiarly fortunate, if, at the close of my public life, I can retire esteemed, beloved and equally respected with my predecessor." “ I expect to be vilified and abused, ” Mrs. Adams admitted in still another letter. “ When I come into this situation…” When her friend and fellow feminist Mercy Otis Warren wrote to Abigail Adams congratulating her on being thrust into “ this elevated position ” as the most politically prominent woman in the United States, the new First Lady responded on the day her husband became president that, “ I shall esteem myself peculiarly fortunate, if, at the close of my public life, I can retire esteemed, beloved and equally respected with my predecessor."

First Lady:

1797, March 4 - 1801, March 4

52 years old

Of the four years her husband served as President, Abigail Adams was actually present in the temporary capital of Philadelphia and then, finally, the permanent " Federal City, " of Washington, D.C. for a total of only eighteen months. She nonetheless made a strong impression on the press and public. Of the four years her husband served as President, Abigail Adams was actually present in the temporary capital of Philadelphia and then, finally, the permanent " Federal City, " of Washington, D.C. for a total of only eighteen months. She nonetheless made a strong impression on the press and public.

Abigail Adams couldn’t help herself from writing in letters and saying in public exactly what she thought. When she looked directly at Alexander Hamilton while speaking to him, for example, she declared that she had just" looked into the eyes of the devil himself." Abigail Adams couldn’t help herself from writing in letters and saying in public exactly what she thought. When she looked directly at Alexander Hamilton while speaking to him, for example, she declared that she had just" looked into the eyes of the devil himself."

Highly conscious of her position as the president's wife, Abigail Adams saw her role largely as a hostess for the public and partisan symbol of the Federalist Party. Abigail Adams made no attempt to hide her contempt for the Anti-Federalists loyal to Jefferson who looked for any chance to publicly attack the Federalist followers of Adams. Almost immediately, the President’s Lady became a popular target of attack. The sarcastic Anti-Federalist Albert Gallatin widely spread the story about a friend who “ heard her majesty as she was asking the names of different members of Congress and then pointed out which were ‘our people. ’” Abigail Adams gave as good as she got, sarcastically calling him "the sly, the artful, the insidious Gallatin..." Gallatin shot back, dubbing her “Mrs. President, not of the United States but a faction.” However sharp, the nickname was accurate. It would stick with Abigail Adams for the rest of history.

Wounded as she was, the remark did not make Abigail Adams recede in public. She was unofficially titled " Lady Adams, " and encouraged such recognition by assuming a visible ceremonial role. She was flattered in welcoming a Native American Indian chief who had come to meet the President but felt his “duty was but in part fulfilled until he had also visited his mother.” She gave permission to a light infantry volunteer regiment to organize under the name of the Wounded as she was, the remark did not make Abigail Adams recede in public. She was unofficially titled " Lady Adams, " and encouraged such recognition by assuming a visible ceremonial role. She was flattered in welcoming a Native American Indian chief who had come to meet the President but felt his “duty was but in part fulfilled until he had also visited his mother.” She gave permission to a light infantry volunteer regiment to organize under the name of the

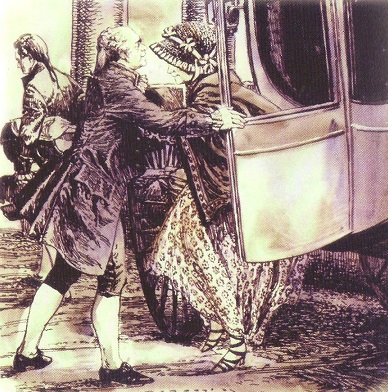

“ Lady Adams Rangers. ” And when she was heading home, north to Massachusetts, she stopped to inspect a New Jersey federal army encampment and even reviewed the troops, reporting a bit sheepishly to the President that, “ I acted as your proxy. ”

With such a high profile, it could therefore hardly have been a surprise to her that slipping out one night to the Chestnut Street Theater to hear a new and stirring march written to honor President Adams while " in-cog, " would be unsuccessful. The editor of the Aurora, an especially vicious anti-Adams newspaper immediately recognized Mrs. President and gleefully reported how “ the old lady ” was over-wrought and ridiculously wept at this rare showing of support for her husband.

Often mentioned in the press, her opinions were even quoted at a New England town hall meeting. Even the private letters exchanged between the presidential couple could be purloined and intercepted by political enemies in the chain of the postal system. It wasn’t long before one of President’s Lady’s stolen letters to the President was being waved about and quoted by a man at a public debate in Massachusetts. Abigail Adams was livid. She wrote: “ I could not believe that any gentleman would have so little delicacy or so small a sense of propriety as to have written a vague opinion and that of a lady, to be read in a publick assembly as an authority. That man must have lost his sense.... It will serve as a lesson to be to be upon my guard. ” She did, however, add the confession that,“ I cannot say that I did not utter the expression…but little did I think of having my name quoted. ” Often mentioned in the press, her opinions were even quoted at a New England town hall meeting. Even the private letters exchanged between the presidential couple could be purloined and intercepted by political enemies in the chain of the postal system. It wasn’t long before one of President’s Lady’s stolen letters to the President was being waved about and quoted by a man at a public debate in Massachusetts. Abigail Adams was livid. She wrote: “ I could not believe that any gentleman would have so little delicacy or so small a sense of propriety as to have written a vague opinion and that of a lady, to be read in a publick assembly as an authority. That man must have lost his sense.... It will serve as a lesson to be to be upon my guard. ” She did, however, add the confession that,“ I cannot say that I did not utter the expression…but little did I think of having my name quoted. ”

Mrs. Adams helped forward the interests of the Administration by writing editorial letters to family and acquaintances, encouraging the publication of the information and viewpoint presented in them. She was sarcastically attacked in the opposition press, her influence over presidential appointments questioned and there were printed suggestions that she was too aged to understand questions of the day. Towards the end of the Adams Administration, there were even Anti-Federalist newspaper editorials which, in attacking President Adams for his choice of some foreign appointees said it was evidence that his more politically astute wife was clearly not in the capital at the time of his decision, but home in Quincy because, “ the President would not dare to make a nomination without her approbation [ approval ]. ”

Indeed, Abigail Adams supported the sentiment behind her husband's Alien and Sedition Acts as a legal means of imprisoning those who criticized the President in public print. Fearful of French revolutionary influence on the fledgling United States, she was unsuccessful in her urging the President to declare war with France. She remained an adamant advocate of equal public education for women and emancipation of African-American slaves.

Her entertainments were confined to a relatively small home in Philadelphia, turned into a hotel after the capital was moved from Philadelphia to Washington, D.C. Although she did host a dance for her son and his friends, she received visitors formally, seated like a royal figure as she had witnessed at Buckingham Palace. She also attempted to influence fashion, believing that the more revealing Napoleonic-style clothing then popular were too indecorous. Her entertainments were confined to a relatively small home in Philadelphia, turned into a hotel after the capital was moved from Philadelphia to Washington, D.C. Although she did host a dance for her son and his friends, she received visitors formally, seated like a royal figure as she had witnessed at Buckingham Palace. She also attempted to influence fashion, believing that the more revealing Napoleonic-style clothing then popular were too indecorous.

Since presidential families were responsible for covering the costs of their entertainments and the Adamses were enduring financial difficulties at the time of his presidency, Abigail Adams's receptions were somewhat spartan.

The first First Lady to live in the White House, she resided there for four months, arriving in November 1800. During that time she famously hung her family's laundry in the unfinished East Room to dry.

Post-Presidential Life:

When Thomas Jefferson finally managed to defeat John Adams in his attempt to win a second term, Abigail Adams was ready to leave politics, writing shortly beforehand, she was “ Sick, sick, sick of public life.”In a November 13, 1800 letter to her son, she reflected: “ The consequence to us, personally, is, that we retire from public life. For myself…I have few regrets. At my age, and with my bodily infirmities, I shall be happier at Quincy. Neither my habits, nor my education, or inclinations have led me to an expensive style of living, so that on that score I have little to mourn over. If I did not rise with dignity, I can at least fall with ease, which is the more difficult task…I feel not any resentment against those who are coming into power… ”

While her central focus in retirement was on her home and raising her granddaughter Susanna Adams to maturity, Abigail Adams nevertheless remained interested in national political issues.

Upon learning of Maria Jefferson Eppes' death, Abigail Adams wrote to the girl's father, President Jefferson, thus initiating a renewal of their contact and while she remained mistrustful of his politics, a new friendship through correspondence opened between Jefferson and John Adams. She corresponded upon at least one occasion with her successor Dolley Madison.

Relieved at the return of her son John Quincy Adams from his diplomatic missions in Europe, Abigail Adams had an initially strained relationship with his English-born wife, Louisa Catherine Johnson. She did not live to see her son become President, which occurred six years after her death. When once approached for permission to publish some of her political letters, Abigail Adams refused, considering it improper for a woman's private correspondence to be publicly divulged.  However, one of her grandsons arranged for the publication of some of her famous letters in 1848, becoming the first published book pertaining to a First Lady. However, one of her grandsons arranged for the publication of some of her famous letters in 1848, becoming the first published book pertaining to a First Lady.

Death:

Her home, Quincy, Massachusetts

1818, October 28

73 years old

Burial:

First Unitarian Church, Quincy Massachusetts

*Not only is Abigail Adams buried beside her husband but also along with their son, the sixth President and his wife, John Quincy and Louisa Catherine Adams.

*Abigail Adams is the first of three First Ladies who is buried on the grounds of a house of faith, the others being Louisa Adams and Edith Wilson, buried at the National Cathedral in Washington.

|