|

Copyright, Attention: This website and its contents contain intellectual property copyright materials and works belonging to the National First Ladies’ Library and Historic Site and to other third parties. Please do not plagiarize. If you use a direct quote from our website please cite your reference and provide a link back to the source.

First Lady Biography: Ellen Arthur

ELLEN LEWIS HERNDON ARTHUR

Birth

30 August 30 1837

Culpepper CourtHouse,Virginia

Ellen Lewis Herndon was born in a house built by her father’s brother, Brodie Strachan Herndon. The structure remains standing, now known as “the Johnson house.”

Father

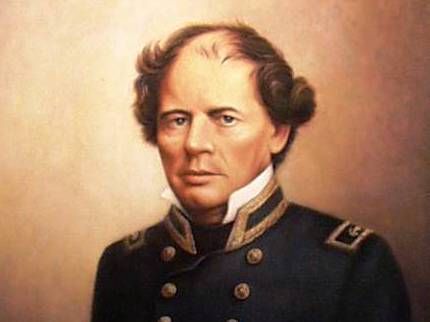

William Lewis Herndon, born 25 October 1814,Fredericksburg,Virginia; naval officer; died 12 September 1857, Atlantic Ocean, off Cape Hatteras,North Carolina in a shipwreck.

Son of a banker, Herndon joined the United States Navy as a teenager, and was made an acting midshipman in 1819. He served on active duty during the Seminole War (1841-1842) and the Mexican War (1847-1848), eventually rising to the rank of Commander in 1855. His most famous assignment, however, was an exploration of the Amazon River(1851-1852). He began the adventure at an altitude rise of 16,699 feet in the Andes Mountains in Peru, eventually following streams into the large river for over four thousand miles, and by foot through the remote jungles. It took a total of 327 days. In the following two years (1852 -1854), he lived inWashington while writing and assembling material for the congressional publication Exploration of the Valley of the Amazon. Son of a banker, Herndon joined the United States Navy as a teenager, and was made an acting midshipman in 1819. He served on active duty during the Seminole War (1841-1842) and the Mexican War (1847-1848), eventually rising to the rank of Commander in 1855. His most famous assignment, however, was an exploration of the Amazon River(1851-1852). He began the adventure at an altitude rise of 16,699 feet in the Andes Mountains in Peru, eventually following streams into the large river for over four thousand miles, and by foot through the remote jungles. It took a total of 327 days. In the following two years (1852 -1854), he lived inWashington while writing and assembling material for the congressional publication Exploration of the Valley of the Amazon.

From this assignment, he took command of the merchant steamship George Law (later renamed theCentral America),beginning in October of 1855. Two years later, while taking the ship from Havana,Cuba to New York, the ship wrecked off the North Carolina coast. After first seeing the full evacuation of passengers in lifeboats led by some of his crew, he and his remaining crew went down with his ship. Dying a hero, his chivalry earned him a posthumous national fame.

Mother

Frances Elizabeth “Kit” Hansbrough Herndon, born 10 October 1817, Culpeper, Virginia; married 9 November 1836, Culpeper, Virginia at St. Mark's Parish; died

5 April 1878, Hyeres, France

Siblings

Only child; Ellen Arthur was the third of seven presidential wives who were only children. The one who was an only child who preceded her was Eliza Johnson; those who followed her were Frances Cleveland, Grace Coolidge, Nancy Reagan (who had a stepbrother), and Laura Bush.

Ancestry

English, Dutch, French; Ellen Arthur’s maternal ancestor who immigrated to the Virginia colony in 1639 from England was John Hanbury (born about 1615). His mother, Adrian Cash was Dutch. Two of her paternal ancestors who immigrated to the Virginia colony, were Meindert Doodes and Mary Geret (both born about 1610), also came from Holland. There is also indication that she was related to early French Hugenots who settled in Virginia.

Religion

Episcopalian

Appearance

Medium height, brown hair, brown eyes

Education

Unknown; school in Washington,D.C.

Life Before Marriage

Few specifics are documented about Ellen Arthur’s earliest years. Described by a contemporary as “one of the best specimens of the Southern woman,” would suggest that she assumed the traditional responsibilities of wealthy southern elite women of her era: the domestic arts, lavish, frequent and generous entertaining, directing the education, religious training and appearance of her children, and commitment to her church parish.

Four months before her birth, Ellen Herndon’s father, then a lieutenant in the United States Navy, was assigned to sea duty and thus absent when she was born. This fact, along with her being an only child, may account for her extremely close relationship with her mother. The family ties between her father to his siblings, their spouses and children were especially tight. Although she was an only child, Ellen Herndon was particularly close to her first “double” cousins, whose parents were the sister of her mother and brother of her father.

In September 1842, Ellen Herndon and her parents moved toWashington,D.C., due to her father’s appointment to the U.S. Navy Department’s Depot of Instruments and Charts, located at the present-day U. S. Naval Observatory. William Herndon’s job opportunity was a result of nepotism, since his superior, Lieutenant Matthew Fontaine Maury (soon-to-be-famous as “Pathfinder of the Seas"), was not only a cousin, but his brother-in-law, married to his sister Ann. His responsibility included assisting Maury to write and publish Sailing Directions, a global navigation guide.

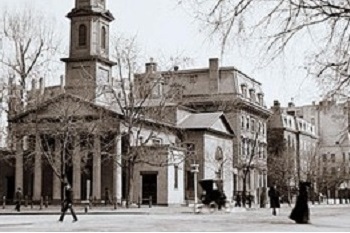

Ellen Arthur’s predominant talent was a beautiful singing voice that was cultivated at a very early age. Her uncle had recorded that singing was also an outstanding gift of her mother, and considering the especial closeness between the two women, it was likely the daughter was emulating her mother. A primary activity of her life in Washington as a young girl was her membership in the youth choir of St. John’sChurch on Lafayette Square, across from the White House.

According to family lore, as a child she became a “close personal friend” of Dolley Madison and visited her “quite frequently.” There was something more to the acquaintance between the young Ellen Herndon and former First Lady Dolley Madison beyond the fact that they shared the same church parish. The window of time they could have known each other, however, ranged from 1842 to 1847, when Ellen Herndon was in an age range from five to ten years old, and Dolley Madison, was in an age range from seventy-four to seventy-nine years old. According to family lore, as a child she became a “close personal friend” of Dolley Madison and visited her “quite frequently.” There was something more to the acquaintance between the young Ellen Herndon and former First Lady Dolley Madison beyond the fact that they shared the same church parish. The window of time they could have known each other, however, ranged from 1842 to 1847, when Ellen Herndon was in an age range from five to ten years old, and Dolley Madison, was in an age range from seventy-four to seventy-nine years old.

In September of 1847, while her father was on active duty during the Mexican War, Ellen Herndon and her mother left Washington, to live in Fredericksburg, Virginiain a house still standing, at Lewis and Prince Edward Streets. However, in 1851, when he was exploring the Amazon River, Ellen Herndon returned to live in the nation’s capital with her mother until 1855. Their return was likely prompted by the now-permanent residency there of Ellen Herndon’s maternal grandfather, Joseph Sumner Hansbrough, who lived there until his death there at age 74 years old, in 1864. He was buried in the famous Congressional Cemetery there.

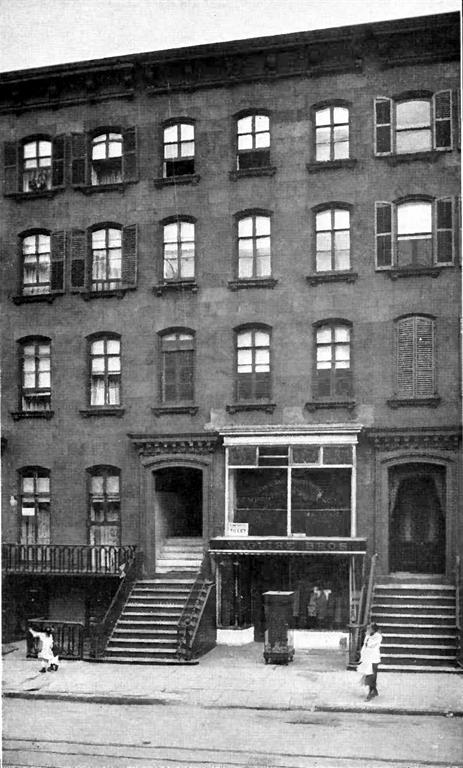

Maturing into her teenage years during her second residency in Washington,D.C., Ellen was able to take full advantage of the social life in which young women of the elite class were encouraged to fully participate. With the great wealth of her mother and the prestige of her father’s military status, she was exposed to the most powerful figures of national politics, society, and the military, who were often entertained by her mother, paternal uncle and paternal aunt. Her father’s command of a merchant steamship based at the port of New York, had them relocated to that city by 1857, moving into a brownstone they bought at 34 West 21stStreet.

Upon William Herndon’s 1857 death on the Central America there was bestowed a host of honors on his wife and daughter. There was a “handsome” public subscription to raise funds for them. An impressive monument was built to him at Annapolis Naval Academy. The Commonwealth of Virginia ordered that a unique gold medal be struck to memorialize Herndon, and it was presented to his widow and daughter. Commodore Maury wrote an official report of Herndon’s heroic last voyage for the Secretary of the Navy. Congress and several State legislatures made official resolutions in his honor. Even the wealthy Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, who had owned the Central America, tried to offer a distraction by having Mrs. Herndon drive his newly-purchased team of well-bred horses. Upon William Herndon’s 1857 death on the Central America there was bestowed a host of honors on his wife and daughter. There was a “handsome” public subscription to raise funds for them. An impressive monument was built to him at Annapolis Naval Academy. The Commonwealth of Virginia ordered that a unique gold medal be struck to memorialize Herndon, and it was presented to his widow and daughter. Commodore Maury wrote an official report of Herndon’s heroic last voyage for the Secretary of the Navy. Congress and several State legislatures made official resolutions in his honor. Even the wealthy Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, who had owned the Central America, tried to offer a distraction by having Mrs. Herndon drive his newly-purchased team of well-bred horses.

Despite the loss of her father, the reality was that most of her life had been spent alone in her mother’s company, William Herndon being a largely absent father. In addition, once a mourning period suitable to the social customs of the upper-class had been observed, Ellen Herndon resumed an active social life with her mother, who was described as having a “cheerful and hopeful disposition.” Throughout the summer months, they moved between the upper-class resorts of Newport, Rhode Island and Saratoga Springs,New York, to socialize with others in their elite circle.

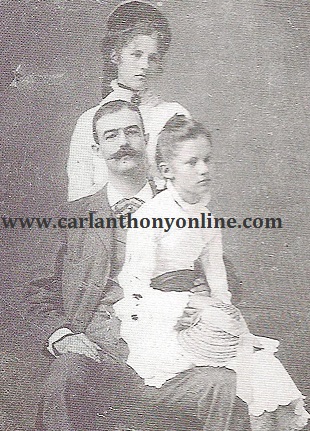

The year after her father’s death, Ellen Herndon was vacationing with her mother in Saratoga, when her cousin Dabney Herndon, then a medical student, introduced her to Chester Alan Arthur, a lawyer, with whom he shared rented rooms in New York. It was Ellen Herndon’s beautiful singing which first captured Arthur’s attention. A year later, in 1858, again at Saratoga, on the front porch of the United States Hotel, he proposed marriage to her, and she accepted. Shortly thereafter, he reminisced to “Nell,” as he always called her, about “the soft, moonlight nights of June, a year ago…happy, happy days at Saratoga- - - the golden fleeting hours at Lake George.”

Marriage Marriage

22 years old, to Chester Alan Arthur (born 5 October 1829 Fairfield Vermont; died 18 November 1886,New York,New York), lawyer, on 29 October 1859, at Calvary Protestant Episcopal Church,New York,New York. Records indicate that the wedding reception in Mrs. Herndon’s home was lavish, the rooms profuse with hanging baskets, vases and table bouquets of flowers, fruit baskets, and thousands of stewed, pickled and raw oysters, lobster and chicken salads, champagnes, brandy, whiskey, sherry, rum and Curacao.

Children

Three children, two boys, one daughter; William Lewis Arthur (10 December 1860 – 5 July 1863), Chester Alan Arthur, Jr. (25 July 1864 – 18 July 1937), Ellen “Nellie” Herndon Arthur [Pinkerton] (21 November 1871 – 6 September 1915)

Life After Marriage

Chester and Ellen Arthur began their marriage living in her mother’s home. Arthur was to assume management of all of his mother-in-law’s investments and real estate holdings. Arthur would find rapid success as an attorney. Although a member of the New York State Militia with the rank of Brigadier-General and soon befriended by the likes of Governor Edwin D. Morgan, who appointed him the state’s Engineer-in-Chief, as well as many New York City and New York State political figures, he hardly earned a large enough salary to afford a luxurious lifestyle that included a three-story Lexington Avenue brownstone with expensive furnishings from Tiffany’s. It was the wealth of Ellen’s mother which enabled the couple to rapidly maintain their status in the elite circles of New York society, of which her mother was already a part.

As Ellen Arthur’s address book, preserved in the Library of Congress attests, she counted the Vanderbilts, Astors, Roosevelts and other leading New York society families among her friends. Without the need to draw a salary large enough to keep up with such a wealthy circle, Arthur was also able to invest his time in the New York Republican Party, eventually becoming a supporter and colleague of political boss and later U.S. Senator from New York Senator Roscoe Conkling. Arthur himself did not run for any state or national office before the 1880 election, when he ran as the G.O.P. Vice Presidential candidate. As Ellen Arthur’s address book, preserved in the Library of Congress attests, she counted the Vanderbilts, Astors, Roosevelts and other leading New York society families among her friends. Without the need to draw a salary large enough to keep up with such a wealthy circle, Arthur was also able to invest his time in the New York Republican Party, eventually becoming a supporter and colleague of political boss and later U.S. Senator from New York Senator Roscoe Conkling. Arthur himself did not run for any state or national office before the 1880 election, when he ran as the G.O.P. Vice Presidential candidate.

Ellen Arthur’s social network widened her husband’s political contacts. It was obvious to many observers that both of them were ambitious for the recognition and prestige that could come through his rise into a powerful political post. Just eighteen months after their wedding, the Civil War began. Through his support and currying of favor with Conkling, Arthur was awarded the position of Adjutant General of New York, with the U.S. Army rank of brigadier general. Forever afterwards, he would insist on being addressed as “General Arthur.”

Although Ellen Arthur remained in the Union territory of he rNew York home throughout the Civil War, she and her mother were distraught by the ongoing conflict, not so much out of a loyalty to the Confederacy or states’ rights but for the well-being of their relatives fighting for the South. There is suggestion of some tension between Arthur and his “little Rebel wife,” as he referred to his wife during the war. Although Ellen Arthur remained in the Union territory of he rNew York home throughout the Civil War, she and her mother were distraught by the ongoing conflict, not so much out of a loyalty to the Confederacy or states’ rights but for the well-being of their relatives fighting for the South. There is suggestion of some tension between Arthur and his “little Rebel wife,” as he referred to his wife during the war.

With a high rank in the Union Army as Quartermaster General and Inspector General of State Troops, his loyalty could not be seen as compromised in any way. Certainly, he risked political attack, at the least, by acquiescing to Ellen Arthur’s insistence that he arrange for her cousin Dabney Herndon (by then a surgeon for the Confederate Army) to twice be released as a prisoner of war from Union prisons, once at Gettysburg. Further, through her husband’s discrete arrangements, Ellen Arthur was permitted to visit her cousin in prison, With Arthur continuing to successfully invest Mrs. Herndon’s wealth, her mother was also able to make substantial monetary gifts and loans to her brother-in-law Dabney Herndon so he could repair his Fredericksburg home, damaged during a Union attack on the town, and to support himself and his three sons Brodie, Jr., Dabney and James, until all of their medical practices could be re-established.

Arthur had been eager to serve on active duty in the Union Army, but legend claims that he did not because Ellen Arthur could not live with the idea of him potentially killing her kinsman. In 1863, two years before the war ended, he resigned to go into private law practice with a clientele of those pressing for war-related damages and for the first time in his career began to amass great wealth on his own.

Still, regardless of sympathy for her native South, Ellen Arthur recognized the value of currying favor with those in power. Consequently, she eagerly accepted the invitations to Abraham Lincoln’s 1865 Inauguration, and the 1874 White House wedding of President Grant’s daughter. In 1871, when President Grant appointed her husband as Collector of the Port of New York, one contemporary said there was “no happier woman” in the country than Ellen Arthur. There existed for many years a jealous rivalry between Ellen Arthur and Ellen Covert Cornell, the wife of Alonzo B. Cornell, New York Republican Party chairman and Speaker of the New York State Assembly,, both ambitious for their husbands’ political success, though the latter did so overtly, while the cooler Ellen Arthur used more personal control, and “smiled at Mrs. Cornell’s methods of resentment.” The “genteel enmity, amounting to almost a feud” was further fueled by the gossip of their defenders. Still, regardless of sympathy for her native South, Ellen Arthur recognized the value of currying favor with those in power. Consequently, she eagerly accepted the invitations to Abraham Lincoln’s 1865 Inauguration, and the 1874 White House wedding of President Grant’s daughter. In 1871, when President Grant appointed her husband as Collector of the Port of New York, one contemporary said there was “no happier woman” in the country than Ellen Arthur. There existed for many years a jealous rivalry between Ellen Arthur and Ellen Covert Cornell, the wife of Alonzo B. Cornell, New York Republican Party chairman and Speaker of the New York State Assembly,, both ambitious for their husbands’ political success, though the latter did so overtly, while the cooler Ellen Arthur used more personal control, and “smiled at Mrs. Cornell’s methods of resentment.” The “genteel enmity, amounting to almost a feud” was further fueled by the gossip of their defenders.

Ellen Arthur had an ethereal presence, her physicality often noted by those who met her. Her pale skin contrasted with her strikingly dark eyes and eyebrows, magnified by her round gutta percha-rimmed spectacles (she was quite near-sighted), the posture of her extremely thin figure always carried in a dignified carriage, always holding her elbows at her waist and clasping her hands at the center of her waist.

Despite her social appeal and the appearance of a charmed life, Ellen Arthur also suffered emotional difficulties. In 1863, her first-born child had died before he was even three years old. In April 1878, she was contacted by telegram that her mother, then visiting France, had died suddenly. It required that Ellen Arthur make the trans-Atlantic voyage to retrieve the remains of her mother. In light of her tremendous bond with her mother, the observations of friends that Ellen Arthur’s “shock and nervous tension” in reaction to Mrs. Herndon’s death “did much to impair her health” was significant.

The depression caused by her having to retrieve her mother’s remains was made all the more difficult by the fact that she had to undertake the responsibility alone; so fully consumed by his political career was Chester Arthur, that he declined to take the time and make the trip with her. Some years later, it was disclosed by her grandson that Ellen Arthur was on the verge of filing for separation from her husband by the end of 1879.

It would often later be claimed that her “rich contralto voice” had turned Ellen Arthur into a “leading soprano” of the Mendelssohn Glee Club, and that, “much in demand,” she responded “with grace, to requests, especially when the proceeds were to be devoted to charity.” An amateur group formed in 1866, they performed in musical competition concerts with other singing groups or at benefit concerts, but also sponsored contests for original compositions, the winning numbers being publicly premiered by the club. The Club had a significant presence in New York’s rich cultural life, a reputation enhanced by its conductor and leader Joseph Mosenthal. The group was “seldom heard in public” but had “established its fame as an unusually good male-voice chorus,” and usually drew a “large and fashionable attendance.”

So prestigious was the Mendelssohn Glee Club that one 16 February 1881 review of a recent concert “fully justified the claim that is made for it as the best drilled amateur society in this country.” The club was kept strictly to forty members, all of them male. Women pianists and singers often appeared in solo performances as part of an evening’s program, their names specifically mentioned in reviews and programs. Women were also members of the original club in the 1880s, before it disbanded and reformed as an all-male club. Ellen Arthur’s name does not appear in the available documentation of newspaper coverage of the Mendelssohn Glee Club’s performances, nor is there a suggestion at which events she may have appeared with them or what compositions she may have performed. Her membership in the group is thus, largely anecdotal, dating from after her death. So prestigious was the Mendelssohn Glee Club that one 16 February 1881 review of a recent concert “fully justified the claim that is made for it as the best drilled amateur society in this country.” The club was kept strictly to forty members, all of them male. Women pianists and singers often appeared in solo performances as part of an evening’s program, their names specifically mentioned in reviews and programs. Women were also members of the original club in the 1880s, before it disbanded and reformed as an all-male club. Ellen Arthur’s name does not appear in the available documentation of newspaper coverage of the Mendelssohn Glee Club’s performances, nor is there a suggestion at which events she may have appeared with them or what compositions she may have performed. Her membership in the group is thus, largely anecdotal, dating from after her death.

On 13 January, 1880 the New York Times reported that Ellen Arthur “is now lying dangerously ill at her home, suffering from an attack of pneumonia of a serious character. The lady was seized with the malady on Saturday last, General Arthur being at the time in Albany, and early on Sunday her illness had assumed such a severe form that he was telegraphed to return to New York at once. He took passage on a milk train, and reached this city late on Sunday night, and has since then been in constant attendance at her bedside. At a late hour last night, Mrs. Arthur was announced to be in a critical condition, and grave fears were entertained that she would not survive the attack.”

Later accounts emphasized that it was after singing in a concert hall, waiting for her carriage while standing in slippers (which would suggest a dance performance, rather than a musical one) on a city sidewalk in a driving rain or snowstorm, or extreme cold, that Ellen Arthur developed a chill that quickly became pneumonia. While the article which first reported her illness noted that she was “an amateur vocalist of most extraordinary merit” there was no mention of Ellen Arthur having recently (or ever) appeared with the Mendelssohn Glee Club or any other singing group. Published records of fundraiser or other concerts in New Yorkat that time make no mention of that club; this omission, of course, does not preclude the possibility they may have done so or that Mrs. Arthur sang with the male group at such an event, or earlier ones. One suggestion that she may have joined in some concerts where members of the club also performed was the newspaper report of her church funeral service, where the “Mendelssohn Glee Club gave a grand rendering of the hymn beginning, ‘There is a blessed home beyond this life of woe.’” It does not, however, mention any affiliation she may have had with the club or what prompted their appearance.

Other later accounts claim that his wife was unconscious by the time Chester Arthur reached her side and unable to recognize or acknowledge him, highly romanticizing the incident or perhaps providing a pathos to suggest guilt he felt at being involved in political business when she fell ill. In fact, he had been in Albany, preoccupied with the task of helping to engineer the re-election of the controversial political boss and his mentor Roscoe Conkling to the U.S. Senate. Whether Arthur suffered a lifetime of remorse for this, however, is purely speculative.

Death

42 years old

January 12, 1880

New York,New York

Burial

Rural Cemetery

Albany New York

Sixteen Months With No First Lady: 19 September, 1881 – 14 January 1883

Ellen Arthur’s funeral was held at her parish, the Church of the Heavenly Rest on 5thAvenue in New York, the services conducted by one of her Herndon-Maury cousins. Her burial ceremony in Albany was attended by a wide swath of powerfu lNew York state Republican figures, including numerous judges and commissioners and the incumbent and former Governors. Earlier in the day, the New York State Assembly had voted a resolution of sympathy for General Arthur and to form an official committee of members to attend the burial service later that day in a nearby cemetery, and further, to adjourn in mourning.

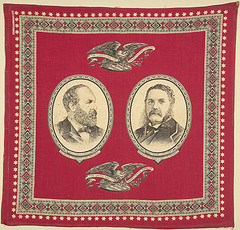

While certainly a sign of respect to Mrs. Arthur, it was also a sign of the significant political support Arthur had managed to accumulate. In fact, his power within the New York Republican Party, among the branch known as the “Stalwarts,” had risen so highly that, less than six months after Ellen Arthur’s death, he was nominated as the party’s vice presidential candidate, on the ticket with James Garfield. At the time, however, Arthur was still deeply depressed over the loss of his wife, remarking, “Honors to me now are not what they once were.”

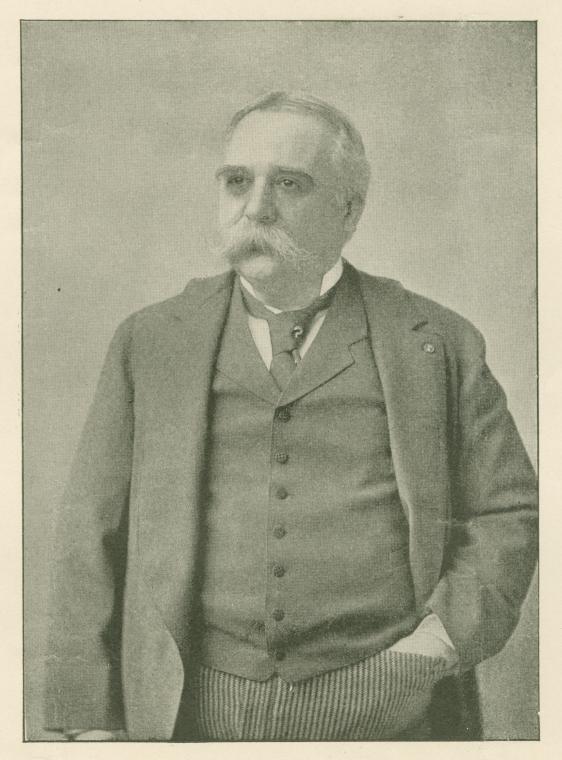

Garfield and Arthur won the election on 2 November 1880, and assumed office on 4 March 1881. Six months later, following the death by assassination of President Garfield, Vice President Arthur assumed the presidency, sworn in at his Lexington Avenue home.

Chester Arthur was the fourth U.S. President who entered the White House as a widower, following Jefferson, Jackson and Van Buren. However, in the intervening forty years since the last widower in the White House, the public expectation that there always be a First Lady (even if it were not the wife of a president but another relative) had been established. Two weeks after Arthur became president, renovation work was begun on the private residential rooms of the White House, thus precluding any immediate occupancy by a presidential family. A period of some ninety days of official mourning for the late President Garfield was to be observed by the federal government, precluding any presidential entertaining.

During this period, Arthur lived and worked out of the Capitol Hill home of Interior Secretary Samuel J. Kirkwood during the week. He returned as often as possible to New York, having his home renovated and prepared to rent to his married nephew and his family, establishing temporary office space in that city in rented rooms at the New York Hotel. The press and the public, however, pressed the issue of a First Lady, as expressed in the 10 November 1881 Washington Post: “The question which now concerns society circles in this city, as well as interests those circles where purely political subjects are discussed is – What lady is President Arthur to install as mistress of the White House during the Administration? “

The paper named several potential candidates. One person high on the list was Sarah Haughwout Howe Roosa, a childhood friend and bridesmaid of Ellen Arthur’s. Highly social, a brilliant conversationalist, intellectual and beautiful, Mrs. Roosa was nevertheless tainted by scandal as a former paramour of Roscoe Conkling’s, the reason for her divorce from her first husband. A second name mentioned was Ellen Arthur’s first cousin Elizabeth Herndon Botts, with whom she had also been especially close and who named a daughter after her. Also speculated about were two of the president’s three married sister, Malvina Haynesworth or Mary “Molly” McElroy. The paper named several potential candidates. One person high on the list was Sarah Haughwout Howe Roosa, a childhood friend and bridesmaid of Ellen Arthur’s. Highly social, a brilliant conversationalist, intellectual and beautiful, Mrs. Roosa was nevertheless tainted by scandal as a former paramour of Roscoe Conkling’s, the reason for her divorce from her first husband. A second name mentioned was Ellen Arthur’s first cousin Elizabeth Herndon Botts, with whom she had also been especially close and who named a daughter after her. Also speculated about were two of the president’s three married sister, Malvina Haynesworth or Mary “Molly” McElroy.

Little was forthcoming from the President. It was learned on 31 October, that he had even consulted former First Lady Julia Grant on the matter. On 20 November, the Washington Post finally reported that, “President Arthur’s plan regarding assistance at his receptions is now said to be not to have any lady remain permanently and preside at the White House. He will, it is said, invite the wives and daughters of the members of his Cabinet to assist him. This plan he has communicated to several ladies, telling them that he confidently counts on their help during the winter.”

The first sign of his decision would be evident at the New Year’s Day Reception on the first day of 1882; however, Arthur received officials and the public that day with a host of other men’s wives: Harriet Blaine, married to the outgoing Secretary of State. Union general’s wife Mary Logan, and spouses of Senators and Congressmen Elizabeth Cameron, Hannah Jones, Mary Miller, Alice Pendleton, and Maria Robeson. Several weeks later, there was a glowing report of Arthur’s first state dinner, and “the absence of a mistress took nothing away from the enjoyableness of the occasion.”

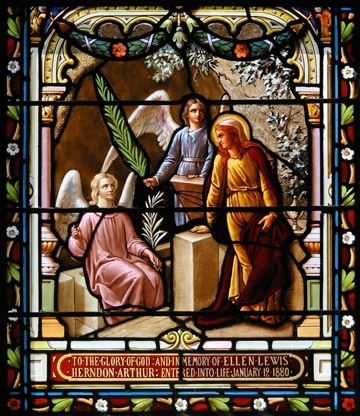

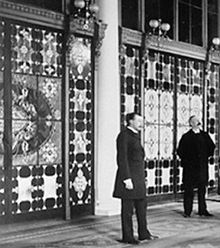

Ellen Arthur’s memory was kept alive by her husband throughout his presidency, in ways both private and public. He paid for the installation of a memorial stained-glass window at St. John’s Church, her childhood parish, which stood directly across Lafayette Square from the White House. The windwo was installed in the south transept of the church. With the lights left on inside the church at night, the illuminated stained-glass could be glimpsed from the second floor private residence rooms of the White House. In fact, President Arthur moved his own bedroom from the traditional presidential suite on the west end of the house facing the South Lawn, to the suite on the west end facing the North Lawn (where the current private Dining Room is located) and the church across the square, enabling to see it from his room. Ellen Arthur’s memory was kept alive by her husband throughout his presidency, in ways both private and public. He paid for the installation of a memorial stained-glass window at St. John’s Church, her childhood parish, which stood directly across Lafayette Square from the White House. The windwo was installed in the south transept of the church. With the lights left on inside the church at night, the illuminated stained-glass could be glimpsed from the second floor private residence rooms of the White House. In fact, President Arthur moved his own bedroom from the traditional presidential suite on the west end of the house facing the South Lawn, to the suite on the west end facing the North Lawn (where the current private Dining Room is located) and the church across the square, enabling to see it from his room.

Although Arthur had his New York brownstone entirely refurbished in the fall of 1881, he insisted that his late wife’s room be kept just as she left it, like a memorial museum room, as if she’d just briefly left. Even her bookmark remained where she had last left it, in the last book she was reading, and her sewing needle kept in place on the crewelwork she was doing. Even her pet birds still lived in their cage in the room. Her burial place in a public cemetery, increasingly visited by the curious, was lavishly landscaped with trees, rose bushes and ornamental beds of geraniums. Although Arthur had his New York brownstone entirely refurbished in the fall of 1881, he insisted that his late wife’s room be kept just as she left it, like a memorial museum room, as if she’d just briefly left. Even her bookmark remained where she had last left it, in the last book she was reading, and her sewing needle kept in place on the crewelwork she was doing. Even her pet birds still lived in their cage in the room. Her burial place in a public cemetery, increasingly visited by the curious, was lavishly landscaped with trees, rose bushes and ornamental beds of geraniums.

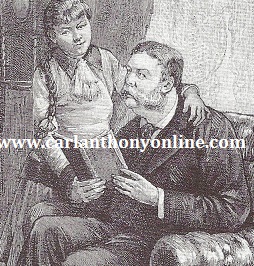

An article by Henry Thurston Peck, twenty years after Arthur’s presidency, first disclosed the intensely personal fact that Arthur kept Ellen’s portrait on a wall in the private quarters and ordered that newly-cut flowers be “heaped” in front of it on a daily basis. He was even reported to be seen carrying violets because it had been her favorite flower. Bringing a small and beautiful black saddle horse to the White House, he insisted it be the one on which his daughter learned to first ride - because it had been her mother’s

. .

Ellen Arthur exercised a posthumous influence on at least four known presidential appointments. President Arthur placed William Arden Maury into the position of Assistant Attorney General in 1882 because he was married to Ellen’s first cousin, Betty Herndon Maury. He also pressed the Postmaster-General to hire as his assistant one Haughwout Howe, the son of Ellen Arthur’s closest friend.

Among Arthur’s most controversial political appointments was making Captain Francis M. Ramsay the Superintendent of the Naval Academy, a decision based entirely on the fact that Ramsay had been a friend of Ellen Arthur’s since childhood. There was nothing amiss in Ramsay’s naval record but he was the lowest officer in rank who had ever been given the prestigious position. It was known in the Navy Department that Ramsay was to be “looked after,” because he had enjoyed an intimate friendship with Ellen and Chester Arthur, and the decision generated enormous covert resentment among naval brass.

The President created more political ill-will with Senator Dan Cameron over the naming of the District Marshal of Washington. Assigning someone to the job was usually reserved as a prerogative of political patronage by the Senate leadership, but President Arthur insisted on hiring one Clayton McMichael for it. The Marshal’s duties involved ceremonial duties at the White House and thus working closely with the presidential family: McMichael and his wife had been close friends with Ellen Arthur – and the President wanted him around simply because of the association with his late wife. The President created more political ill-will with Senator Dan Cameron over the naming of the District Marshal of Washington. Assigning someone to the job was usually reserved as a prerogative of political patronage by the Senate leadership, but President Arthur insisted on hiring one Clayton McMichael for it. The Marshal’s duties involved ceremonial duties at the White House and thus working closely with the presidential family: McMichael and his wife had been close friends with Ellen Arthur – and the President wanted him around simply because of the association with his late wife.

The public did not always share Arthur’s sanctity for his late wife. There were often humorous references to the chance women had to become First Lady. After a report of the President “fishing earnestly,” the magazine Judge asked, “Do you hear that, girls? Why weren’t some of you on hand to be caught?” A political figure quipped that Arthur should “be as free to choose his Cabinet as to select a wife,” the Cleveland Herald mused, “But why so slow about either of these luxuries?” When a British actor, sailing to the United State swith his troupe, was wildly cheered for his shipboard performance, he offered “three cheers” for President Arthur, and, “Another for Mrs. Arthur!” Reported as a sign of disrespect, he had to backpedal in apologetic interviews, his agent assuring a journalist that the actor wasn’t known to “speak an unkind word or do an ungentlemanly action.”

In the rush of sudden arrangements that had followed President Garfield’s death and funeral in Washingtonin late September of 1881, the new President had been delayed in re-uniting with his nine-year old daughter Nellie. She was then being kept away from their New York home as a means to protect her from the press, in the care of her aunt Molly McElroy at Albany. When the new president’s sister left her niece with her husband, and came to New York to arrange the transfer of her brother’s household to Washington, it was widely speculated that she would serve as White House hostess. A retraction followed that “it has not yet been decided.”

While there’s no documentation to prove that he resisted having a feminine companion due to his lingering grief or refused to consider anyone taking what would have been her proud place beside him in the White House, by early 1883, Chester Arthur seemed to reconsider his initial decision. One other factor, previously ignored in this context, is the fact that in early October of 1882, the President learned that he had a kidney disease which would likely prove fatal: it may have prompted his desire to be closer to not only his daughter but his sister. While there’s no documentation to prove that he resisted having a feminine companion due to his lingering grief or refused to consider anyone taking what would have been her proud place beside him in the White House, by early 1883, Chester Arthur seemed to reconsider his initial decision. One other factor, previously ignored in this context, is the fact that in early October of 1882, the President learned that he had a kidney disease which would likely prove fatal: it may have prompted his desire to be closer to not only his daughter but his sister.

MARY “MOLLY” ARTHUR MCELROY

Born

5 July 1841

Greenwich, New York

Father

William Arthur, born 5 December 1796, County Antrim, Ireland; teacher, author, genealogist, law student, Baptist minister; immigrated first to Stanstead, Quebec, 1815, migrated to Burlington, Vermont, 1835; died 27 October 1875, Newtonville, New York

Mother

Malvina Stone Arthur, born 24 April 1802, Berkshire, Vermont; married 12 April 1821, Dunham, Quebec, Canada; 16 January 1869, Newtonville, New York

Religion

Baptist

Education

Early education, unknown;Emma Willard Seminary,Troy,New York, approximately 1858-1862. Receiving a rigorous education that was intended to be equal to those provided to young men, Molly Arthur McElroy was taught history, geography, science, French and specialized in a course of study in its normal school, to prepare for a career as a teacher. The founder’s belief that women’s education was of the highest importance to the gender curiously had her opposing women’s suffrage out of fear that a backlash against it might encroach on the educational gains made by women. It was an attitude that may have been shaped Molly McElroy’s similar view.

Appearance

Small in height; light brown hair, light-blue eyes

Marriage

19 years old, to John Edward McElroy ofAlbany,New York, (born, 1832, place of birth unknown; died 1915,Albany,New York) on 13 June 1861, place unknown. John McElroy was President of the Albany Insurance Company. He began his business career by working in his father’s dry-goods store, and then was made head of a steamship agency. In 1882 he became Secretary of the Albany Insurance Agency. He was active in upstate New York historical societies and a Regent of the University of New York. His brother William was an editor and lecturer.

Children

two sons, two daughters; May McElroy [Jackson] (1862-?); William McElroy (1864-1892), Jessie McElroy (1865-?), Charles Edward McElroy (1876 -?)

Life before the White House

Other than the facts that she was the wife of an Albany insurance salesman and raised four children, little documentation is readily available about Mary Arthur McElroy before her brother became President. A 25 July 1883 article in the Washington PostquotedThe Tarboro Southerner,a North Carolina paper, in claiming that she had once taught at the private Cobb School in the Edgecombe County, North Carolina.

It is clear that following Ellen Arthur’s January 1880 death, Molly McElroy assumed responsibility for the care and education of her niece “Nellie” for two years of school terms, starting with the winter-spring term of 1880 on, through the fall-winter term of 1882. The name of the Albany school where she enrolled her niece, or whether it was a private or public institution, however, is unknown. Molly McElroy was known to have encouraged her niece to pursue music as a way to honor the memory of her late mother.

Thrust into the presidency, Chester Arthur relied upon other siblings as well. His sister, Regina Arthur Caw was left to oversee the completion of his Lexington Avenue home’s renovations through the fall of 1881. When Nellie and her brother Alan, came with their father to visit the White House after all spending the 1881 holiday season together in New York, the president’s son was old enough to return to Princeton University on his own but the little girl was escorted back up to Albany by her uncle, the president’s brother William Arthur. After a year without a First Lady, President Arthur finally decided he needed one.

Tenure as First Lady

41 years old

14 January 1883- 4 March 1885

Chester Arthur’s desire to have his daughter Nellie now live permanently with him in the White House was the determining factor which led to the girl’s supervisor, his sister Molly McElroy, serving as his First Lady, but tracing the progress of her presence evidences that he came to appreciate the value of a designated First Lady. Yet even one full week after she had first arrived on January 14, with her eldest daughter May, the press reported that she was only “visiting,” and “may not remain long,” preferring her “books” over an active social life.

As the 1883 social season got underway, however, Molly McElroy neither returned to Albany– nor was asked to by the President. On January 24, she received guests with the President at a diplomatic corps dinner, seated beside the Haitian Ambassador, directly across from the President, who had placed her in a visible spot with the protocol rank of a Chief Executive’s family member. She again received guests with him at a formal dinner two days later, and the next morning she hosted her own first afternoon reception.

Standing in front of the oval divan in the Blue Room, she began to host a weekly public reception on Saturdays, largely for women who worked weekdays and would otherwise have been unable to meet her. She also received delegations such as the Psi Upsilon Society along with the President, and was the most prominent figure among numerous officials on a Sunday presidential cruise down the Potomac. She also began taking advantage of the presidential box at the theater, including a 27 January 1883 performance of “Patience” that included the extremely rare instance of the President attending Ford’s Theater, where Lincoln had been shot. Standing in front of the oval divan in the Blue Room, she began to host a weekly public reception on Saturdays, largely for women who worked weekdays and would otherwise have been unable to meet her. She also received delegations such as the Psi Upsilon Society along with the President, and was the most prominent figure among numerous officials on a Sunday presidential cruise down the Potomac. She also began taking advantage of the presidential box at the theater, including a 27 January 1883 performance of “Patience” that included the extremely rare instance of the President attending Ford’s Theater, where Lincoln had been shot.

Molly McElroy’s unusual status whetted interest in Washington. Any bit of information about her was eagerly sought. An initial description only provided a physical composite: “…she resembles the President only about the eyes…she has a dainty, petite figure, being both short and slight, and is pale as if she did not enjoy the best of health. She is very modest…”

Soon enough she was being feted as the guest of honor at luncheons hosted by the curious wives of the Chief Justice and Secretary of State and she began to garner more attention than the President when she joined him at dinners in the homes of Cabinet members. Without the status of a presidential spouse, she felt unbound by the unwritten social coda that had dictated the social interactions of her predecessors who had been wives, and she freely attended social events in private homes.

“Now that she feels better acquainted, Mrs. McElroy seems to enjoy society greatly and shows her talent for ready conversation,” reported the social columns of the Washington Poston 26 February 1883. After two months, even the President now felt comfortable with the presence of an official White House hostess. On the eve of her return to Albany, following the end of the series of official dinners he was expected to host as President, Arthur felt compelled to honor his popular sister at a farewell dinner on March 11.

That summer, when the President left for a fishing trip in Yellowstone, he again put his daughter in Molly McElroy’s care. Using a prerogative indicative of a public official rather than a private citizen, she took the president’s daughter, along with her own two girls, May and Jessie, on a U.S. Navy cutter for a vacation on Block Island and Newport, Rhode Island. She also took advantage of the presidential privilege to live during the warm weeks of autumn and late spring at the nearby government-owned Soldier’s Home, a nearby retreat from the White House in a pastoral setting.

Although his family members were able to escape much press notice, there was an unusually strong degree of coverage about the President’s personal life, with reports on everything from his cigars, open-air carriage blankets, hats, fishing equipment and always his clothes.

By October 3, it was reported that Mrs. McElroy would “take charge” at the White House for the 1883-1884 social season. Alongside the President in his doeskin trousers and lavender necktie and gloves, Molly McElroy came especially to Washington to receive officials and the public at the 1884 New Year’s Day Reception, and then returned for three weeks to New York.

While it was clear that President Arthur still determined the roster of official White House entertaining, he would not make any final decisions until he consulted with his new First Lady. As the 23 January 1884 Washington Pos treported, “The announcement of the programme of official gayeties at the White House has been delayed until now, on account of the absence of the President’s sister, Mrs. McElroy.” Four days later she was back at the White House, and hosting her first 1884 reception. Since Arthur did not use the bedroom in the southwest corner of the White House traditionally reserved for the Chief Executive, he turned it over to her.

It took time for Molly McElroy to fully acclimate to the physical demand of standing and shaking hands on receiving lines for hours on end. At one of her Saturday receptions, she became fatigued and had to leave her post to rest. She returned, only to be again “overcome by the closeness of the room,” and retreated a second time. She came back, and “laughingly announced herself as quite able to continue the reception,” staying until the end. By her second year, she had grown into the role. Described in a New York Sun article in February of 1884, as “lively” and “self-possessed,” it was now Molly who was reassuring the uncertain Haitian, Chinese and Russian diplomats with a limited understanding of English, “when they are floored by the mysteries of the menu.”

Unlike an increasing number of her recent predecessors, Molly McElroy did not attend any charity events or sponsor any causes independent of the President. She agreed to attend a 29 January 1884 charity ball for Children’s Hospital of Washington only because her brother was going. Even though her appearance at such public events generated tremendous interest, she kept a lower profile than had she been a president’s wife. While joining the President at a fancy masked ball, she remained one of the few women who did not wear a costume, preferring instead to watch the pageant of costumes, dancing and other festivities from an upper-floor supper room. Along with him, she attended the opening night of Washington's new Albaugh's Grand Opera-House and Armory.

Perhaps due to the unorthodox circumstances of having a First Lady begin her tenure well into an Administration, Chester Arthur seemed willing to break with custom in hosting his state dinners. Beginning with an 11 February 1884 diplomatic corps dinner, he increased the traditional number of dinner guests by twenty-five percent.

A month later, at their dinner for the Senate, President Arthur and Mrs. McElroy broke with tradition in several ways. The invitation of the famously late-dining President who it was publicly acknowledged, slept until eleven in the morning, called for entertainment first, to be followed by a midnight supper, complete with champagne. As Arthur escorted their special guest, the legendary Swedish operatic soprano Christina Nilsson and a Senate wife by the arm through the three smaller reception rooms, the First Lady took on the separate duty of standing alone in the East Room to welcome arriving guests, standing just inside the doors. Nilsson then sang and played the piano, including the old standard, “Way Down Upon the Suwannee River.” Afterwards, brother and sister led their guests into the State Dining Room for the rich and lavish midnight dinner.

As her brother shattered precedent, so too did Molly McElroy. In 1884, she decided to remain in Washington longer than she intended, and to extend her weekly receptions beyond Ash Wednesday, breaking the observed social dictum of suspending large social events through the Lenten season.

Over three consecutive spring seasons, Molly McElroy’s series of ten weekly open-house receptions developed subsequent innovations. Wearing primarily black or shades of lavender or grey, she had the rooms illuminated with gaslight and heavily banked with plants, ferns and flowers.

Another innovation was having a string orchestra of Marine Band playing music continuously. At all of them, she would arrange for “assistant hostesses,” of varying ages, arranging them in the different state rooms in receiving lines. The lead hostess in each room would introduce the guest by name to the next hostess at her right, and thus the guest would be passed down along through the rooms.

After all of her hostesses had finished shaking hands, often with upwards of 2,000 guests each week, Molly McElroy invited them upstairs to the family quarters. There she had a buffet table set in the center of the long West Sitting Hall spread with tea sandwiches and refreshments. The post-reception upstairs luncheons soon assumed the same level of planning that the large party preceding it had. Molly McElroy also welcomed several of her predecessors to the White House, hosting an elegant private luncheon for Julia Grant, and asking Washington residents Julia Tyler and Harriet Lane to serve as hostesses at some of her receptions.

In time, her husband and each of her four children would come stay for a period of time at the White House, many of them congregating there over Easter, along with other members of the extended Arthur family. Molly still took direct responsibility for her niece, bringing her to Governor’s Island in New York for example, for a several day 1884 spring vacation visit, while the President remained in the White House.

The St. Louis-Dispatch would report that Mrs. McElroy was “very retiring in her looks, and without ambition for public recognition” and was “seen little by Washington generally and has only been known personally to a circle extremely limited,” but by 10 July 1884, it would declare that she was “the acknowledged mistress of the White House.” As she became more comfortable in the permanence of her role, Molly McElroy began to indulge her enjoyment of horse riding and increased her skill, making good use of the White House stable of fine horses. Some reports also suggest that she also began taking French lessons while living there.

Although briskly practical in her interaction with the White House staff, she was noted by some of them for her tact and unpretentiousness. In June of 1884, she was leading a tour of well-dressed women carrying parasols in eight open carriages, showing off the beauty of Canadarago Lake in New York State. At the same time, a State Board of Underwriters convention was taking place there and the New American Fire Brigade decided to put on a demonstration of some new fire-fighting equipment for them. They focused their high-powered hoses on some distant houses that were well blocked by thick, high trees – and ended up spraying and drenching the First Lady and her guests. While the women dashed into their hotels, running to change into dry clothes, Molly McElroy “took the whole affair as a joke.”

Her tendency toward caution was a matter of striving to avoid saying or doing anything which could be misinterpreted or reflect poorly on the President. She later reflected that, “When I went to the White House, I was absolutely unfamiliar with the customs and formalities.” While she resisted being drawn into any actions that could be perceived as political, some of her decisions as hostess did carry direct political implications. Molly McElroy politely resisted lobbying efforts from the Women’s Christian Temperance Union to influence the President to re-enact the Hayes ban on alcohol, or even to make a personal declaration that she would not imbibe in any spirits either in private or public at the White House.

After enjoying an August 1884 respite with the President, his children and her own family at Lake Mohonk ,New York, Molly McElroy returned with Nellie and the President to the Soldier’s Home a few weeks later. She remained there for two months, staying to celebrate Thanksgiving with the Arthur family, then returning to her own family in Albany for Christmas.

At the 1885 New Year’s Day reception, she took her place in the East Room, wearing violet satin, beside her brother in his Prince Albert-style suit, his spectacles dangling from a black silk thread, a rosebud in his button hole, and a pearl pin holding his black satin scarf. For the first and only time, he finally permitted the general public see and to meet his daughter. Dressed in white, the now-thirteen year old First Daughter Nellie Arthur stood in the Green Room at the head of a receiving line that included her cousins May and Jessie, and schoolgirl friends.

Several weeks later, at her last public reception, the curiosity and popularity that Molly McElroy had unwittingly generated by the unusual circumstances of her becoming First Lady, prompted an unexpected mob scene. The White House was overcome with 3,000 people – as many men as women, including Adolphus W. Greely, Arctic explorer and a celebrity of the era. So jammed were the doors and halls, that people were found entering from the basement kitchen doors, and over boards through the windows. One Senator entered through the front door, but descended the servant staircase, walk through the garden, ascend the back portico stairs and then enter through a window in the Blue Room. The musicians in the hall were literally pushed from their places in the corridor.

In the first days of March 1885, despite the fact that their brothers led the opposing political parties, Molly McElroy formed a friendly alliance with her incoming successor Rose Elizabeth Cleveland, sister of bachelor president-elect Grover Cleveland. The unusual transition generated particular notice as the only time in history when the only two presidential sisters to serve as First Ladies succeeded each other. A further curiosity was that both women were residents of Albany. When Molly appeared at the Cleveland Inaugural ceremony only to find the seat reserved for her taken by Rose, the latter relinquished it for the former. Some two hours later, Molly McElroy hosted a final White House luncheon, to honor Rose Cleveland.

Life After the White House

Molly McElroy stayed in Washington with her brother for several weeks after they moved out of the White House, a guest of the Freylinghausen family. After a farewell reception for her, hosted by Senator and Mrs. Pendleton, she resumed her relatively quiet life in Albany,New York. Four years later, in early March 1889, she returned to the White House as the guest of honor at a luncheon hosted by President Cleveland’s wife Frances, who he had married in June of 1886. That evening she joined the President and Mrs. Cleveland, along with former First Lady Harriet LaneJohnston, at a private dinner.

The father of Molly McElroy and Chester Arthur had emigrated in 1815 from his village of Cullybackey,Northern Ireland to Durhar, in Quebec, Canada, and subsequently to America. Molly McElroy took an active interest in his family and her Scotch-Irish ancestry. In 1886, she travelled to Northern Ireland, visiting her paternal relatives and ancestral homestead, along with her nephew, the former President’s son Alan. She lent ongoing support to the eventual restoration of the homestead as an historical site.

When the former President died in 1886, Molly McElroy took charge of the funeral arrangements and asked former Presidents Hayes and Cleveland to serve as her brother’s honorary pall-bearers, although Cleveland gently resisted her decision, indicating that their status should have them rank higher. She assumed legal guardianship and served as an adoptive parent to her orphaned niece, while her nephew Alan went to live in Europe.

Although she had assumed the role of White House hostess at public events rather late in her brother’s presidency, Molly McElroy assumed the role most often undertaken by presidential widows. She became the primary figure to maintain her late brother’s legacy, attempting to help her nephew and sons in gathering whatever papers of his they could to donate to the Library of Congress, and unveiling his statue in Madison Square, in New York, in 1899. Although she had assumed the role of White House hostess at public events rather late in her brother’s presidency, Molly McElroy assumed the role most often undertaken by presidential widows. She became the primary figure to maintain her late brother’s legacy, attempting to help her nephew and sons in gathering whatever papers of his they could to donate to the Library of Congress, and unveiling his statue in Madison Square, in New York, in 1899.

Mary McElroy and her husband were early and strong advocates of civil equal rights for African-Americans, a tradition in the Arthur family. As a young attorney, Chester Arthur had famously won two civil rights cases: one which declared that any African-American slave who came to the free state of New York would be considered free; he also defended and won the legal right of an African-American woman to ride in the New York City trolley-car system.

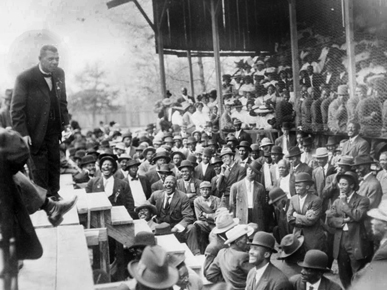

In June of 1900, Mary McElroy and her husband invited the famous African-American educator Booker T. Washington to address the Regents of the University of New York, and he was the guest in their Albany home, reflecting a progressive attitude rare for that era. It spared the distinguished educator any potential conflicts with local hotels which enacted an unofficial discriminatory policy.

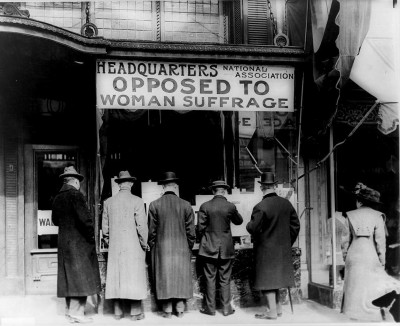

Molly McElroy remained a lifelong resident of Albany, active in its civic and cultural life. She avidly opposed suffrage for women, however, and became a prominent and active leader in the Albany Association Opposed to Suffrage.

During the summers, Molly McElroy frequented Cooperstown,New York while often visiting Atlantic City,New Jersey shore in the early spring. She died there suddenly while on a visit.

Death

76 years old

8 January 1917

Burial

RuralCemetery

Albany,New York

Much of the material related to Ellen Herndon Arthur’s parents, uncles, cousins and ancestry is from Flanaganfamily.net.

|