|

Copyright, Attention: This website and its contents contain intellectual property copyright materials and works belonging to the National First Ladies’ Library and Historic Site and to other third parties. Please do not plagiarize. If you use a direct quote from our website please cite your reference and provide a link back to the source.

First Lady Biography: Edith Roosevelt

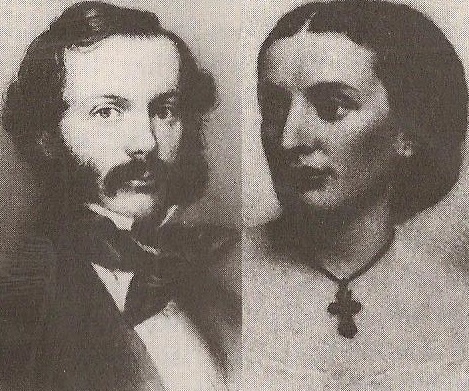

EDITH KERMIT CAROW ROOSEVELT

BIRTH:

Norwich, Connecticut

6 August 1861

Her middle name was the surname of a paternal great-uncle, Robert Kermit.

FATHER:

Charles Carow, (born 4 October 1825, New York, New York, died 17 March 1883). Son of a successful mercantile family, Carow pursued an import-export business. Shamed by the financial difficulties of her father and the resulting deprivations she perceived these matters to have effected on her childhood, Edith Roosevelt made a lifelong effort to destroy many records and accounts about him.

MOTHER:

Gertrude Elizabeth Tyler (born 1834, Norwich, Connecticut, died 27 April 1895, Turin, Italy) educated in New York and in Paris, France where she joined her father during his business endeavors there. Married, 8 June 1859, Christ Episcopal Church, Norwich, Connecticut. Within three years of Edith Roosevelt’s birth, her family relocated to her childhood home on Livingston Place and Fourteenth Street, New York City. Beset by severe alcoholism and a serious fall and concussion, Charles Carow’s success began to rapidly fade.

BIRTH ORDER AND SIBLINGS:

Second of three; one brother, one sister; brother [name unknown] (born 26 February 1860, died August 1860); sister Emily Carow, (18 April 1865 – 19 March 1939)

ANCESTRY:

French, English; Edith Roosevelt’s direct paternal ancestors were the Quereau family from France. After immigrating to New York in 1635, they changed the spelling of their surname to Carow. As Protestants (“Hugenots”), they were persecuted by the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes and fled to the American colonies, arriving and settling in New York. She shared a common ancestor with writer Edith Wharton, whose grandfather’s grandfather was Edith Carow’s great-grandfather’s grandfather Edith Carow’s maternal grandfather Daniel Tyler III was a cousin of Aaron Burr, and his mother was the granddaughter of the famous religious leader Jonathan Edwards. The Tyler family immigrated in 1638 from Shropshire, England.

RELIGIOUS AFFILIATION:

Episcopalian

EDUCATION:

Private kindergarten and primary school education, the Theodore Roosevelt, Sr. home, 28 East 20thStreet, and Anna Bulloch Gracie home, Park Avenue, New York, New York, approximately September 1864-April 1869.As a child, Edith Carow and her sister Emily were raised by an Irish immigrant nursemaid, Mary Ledwith, who spoke frequently of the impoverished life she had left in Ireland. Similarly, it was through Anna Bulloch Gracie, another woman mentor of family association and the sister of Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt, Sr. that she learned how to read, along with the Roosevelt children (Elliott, Theodore, Corinne and Anna). Anna Gracie further instructed Edith Carow in needlework, with other girl students, at her rented home on Park Avenue. Theodore Roosevelt, Sr. also taught Edith Carow and his own children in natural studies with trips to the countryside, wrote plays for them to memorize lines and perform and gave them topics to prepare oral recitations on. Early on, Edith Carow evidenced a voracious appetite for reading and poetry.

Dodsworth School for Dancing and Deportment, Twenty-Sixth Street and Fifth Avenue, New York, New York, 1869-1871.Here Edith Carow was taught not only how to formally dance, but to affect the social mannerisms which denoted the upper-class.

Louise Comstock Private School, West Fortieth Street, New York, New York, 1871-1879.Under the influence of the disciplinarian headmistress, Edith Carow developed a highly moralistic and religious sensibility which forever marked her character. She excelled in writing and developed a lifelong love of Shakespeare. Among the subjects she studied were English History, English Literature, Latin, German, French, zoology, botany, physiology, elemental arithmetic, philosophy, penmanship, singing, and music appreciation. With fellow students, she attended symphony concerts, choral performances, the theater, the circus, and military review drills.

LIFE BEFORE MARRIAGE:

Edith Roosevelt’s earliest life was intertwined with that of Theodore Roosevelt. From the time she was a toddler she had been raised alongside his sister, her lifelong friend Corinne Roosevelt. In April of 1865, four months short of her fourth birthday, she joined the Roosevelt children at their home, including another brother Elliott (father of future First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt), to watch the funeral procession of President Abraham Lincoln pass in the streets below. As young children, Edith Carow and Theodore Roosevelt formed an extremely close bond as friends and companions.

By 1867, her father’s sudden loss of income led to his permanent state of unemployment and left the family homeless. Edith and her family had to live with a widowed great-aunt during the winter months and her maternal grandparents at their Red Bank, New Jersey summer home. In 1871, her family eventually relocated from the Union Square district of New York to a midtown brownstone at 200 West Forty-Fourth Street. In the summer of 1879, the Carow family relocated to another home, at 113 East Thirty-Sixth Street, in New York.

Separated from the Roosevelt children during two periods of lengthy overseas travels, upon their return Edith Carow and Corinne Roosevelt founded a literary society in the winter of 1872, for their young women friends. Meeting weekly on Saturdays, the twelve members read aloud their works of poetry and essays to each other, all of them transcribed by Edith Carow afterwards. She also began to make frequent visits to the Roosevelt family at their summer home on the north shore of Long Island, in the village of Oyster Bay. There she learned to camp under the stars and was often taken out for long row-boat rides by Theodore Roosevelt who named his vessel after her. Spending most of her summer with her maternal grandparents at their farm Barbary Brae in Monmouth County, New Jersey developed in her a lifelong passion and expertise for the natural world of wildflowers, animal and insect life at the seashore life.

Despite leaving New York to begin his higher education at Harvard College in the fall of 1876, Theodore Roosevelt continued his friendship with Edith Carow and she even joined his family in visiting him there in 1877. From within the family it later emerged that he had proposed marriage to her that year and again the following year. Claims that her grandfather and his father opposed the union due to rumors of potential physical disabilities within the opposite families were believed reasons they did not become engaged. Established is the fact that they had a heated quarrel in the summer of 1878. Returning to Harvard in the fall, Roosevelt then met Alice Hathaway Lee, who he would marry as his first wife. During the 1879-1880 winter holiday season, Alice Lee visited the Roosevelt family and met Edith Carow.

Although her grandfather’s 1882 death left Edith Carow’s mother with an inheritance of principal she was only allotted the annual interest from it, according to Edith’s late grandfather’s will. The death of her father four months later made it apparent to his widow and two daughters that they were unable to maintain their elite lifestyle in New York and the three women made plans to move to Europe in the spring of 1886, intending to settle in Italy but making an initial stay in London.

During the time of Theodore Roosevelt’s marriage to Alice Lee, Edith Carow mused about the idea of marrying someone of wealth to provide for her but recognized she was unable to make such a compromise. On two known occasions, she did appear with men as her escorts, one whose name remains unknown and another known only as Mr. Stratton, but the extent of her relationship with either is unclear. In the eighteen months following the death of his first wife, Theodore Roosevelt made only brief visits to his siblings in New York, focused on the Dakota ranchlands he had purchased and was developed. He carefully avoided any direct contact with Edith Carow but they had a chance meeting at the home of his sister in September of 1886.

Despite his assertion that “I utterly disbelieve in and disapprove of second marriages; I have always considered that they argued weakness in a man’s character,” Theodore Roosevelt proposed marriage to Edith Carow in November of 1885. She accepted, although they agreed to keep their future marriage a secret from friends and family. As planned, Edith Carow, her mother and her sister, went to live in London. A year later, Roosevelt crossed the Atlantic to marry her. While making his voyage, he met and quickly befriended British diplomat Cecil Spring-Rice who not only became the best man at his wedding but would prove to be a crucial political ally to both Theodore and Edith Roosevelt.

MARRIAGE:

25 years old, 2 December 1886 to Theodore Roosevelt, rancher and author, (27 October 1858, New York, New York, died 6 January 1919, Oyster Bay, New York) at St. George’s Anglican Church, Hanover Square, London, England. After their wedding ceremony, the Roosevelt took a honeymoon in France, visiting Paris, Lyons, Marseilles and Hyeres in the Provence region and then Florence, Rome, Venice, Pompeii, Naples, and Capri., joined by her mother and sister who settled in Rome to live. An erroneous account of the Roosevelt marriage, confusing her maiden name “Carow” with the aristocratic Maryland “Carroll” family conveyed the false impression in U.S. newspapers that she was six years younger than her real age and a Roman Catholic.

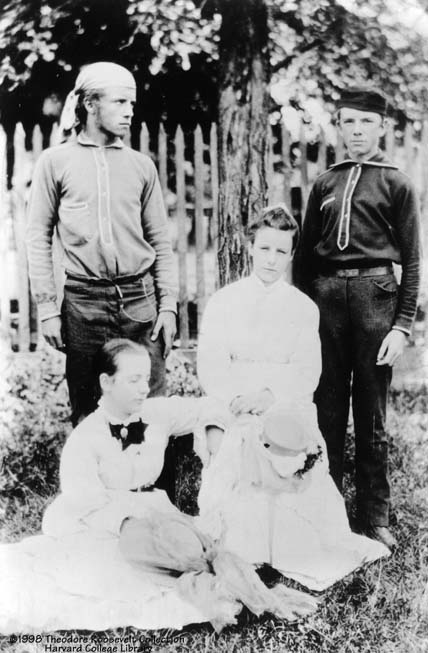

CHILDREN:

four sons, one daughter: Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. (12 September 1887 – 11 July 1944), Kermit Roosevelt (10 October 1889 – 4 June 1943), Ethel Roosevelt [Derby] (13 August 1891 - 10 December 1977), Archibald Bullock Roosevelt (9 April 1894 – 13 October 1979), Quentin Roosevelt (9 November 1897 – 16 July 1918)

Edith Roosevelt became pregnant with her first child while on her honeymoon. She was in close accord with her husband’s strict and pronounced moral code and designation of gender roles: all citizens should be encouraged to assume the role of parents in society and those who did not should be penalized by federal tax; men should remain celibate if unmarried; those convicted of rape should receive the death penalty.

Edith Roosevelt suffered at least two known miscarriages, once early in her marriage, on 8 August 1888 and another time while serving as First Lady, on 9 May 1902.

It was Edith Roosevelt who insisted that she raise as her own daughter the lone child of Theodore Roosevelt’s first marriage, Alice. It can be speculated that the child he only referred to as “Baby Lee” was a living reminder to him of the painful loss of his first wife. Raised for the first three years of her life by his sister Anna, Theodore Roosevelt was inclined to continue this arrangement, telling her “if you wish to you shall keep Baby Lee.” Once he had decided to remarry, Roosevelt warned his sister Corinne that he “did not care to see” his late first wife’s sister during a visit to New York. Edith Roosevelt insisted that her stepdaughter call her “Mother,” but also arranged for Alice to spend three weeks each spring and fall with the family of her late mother.

Scandalized by the fact that her husband’s brother, Elliott Roosevelt, fathered an illegitimate child by one of his servants, Edith Roosevelt sought to limit the visits of his daughter, future First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Famously calling her niece an “ugly duckling [who] may turn out to be a swan,” she did not encourage a close relationship between Eleanor and her own stepdaughter Alice, who later became rivals both in private and public life.

LIFE AFTER MARRIAGE:

While Edith Roosevelt chose motherhood as the focus of her life, she did not disdain those who pursued higher educations and professional careers. She would come to eventually support a women’s right to vote. During their honeymoon, she assumed the role of editor for several magazine articles he wrote. Shortly thereafter, she formed a bond with his political mentor, U.S. Congressman Henry Cabot Lodge through their mutual passion and expertise in English literature.

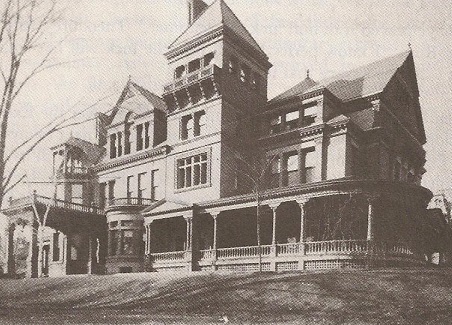

Upon return from her honeymoon, Edith Roosevelt worked closely with her new husband in furnishing their large, permanent Oyster Bay home, the name changed from “Leeholm” to “Sagamore Hill,” thus further erasing the lingering memory of the first Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt, Alice Lee, for whom it had been built and who had chosen the basic furnishings. Edith Roosevelt also placed a sudden distance between herself and her longtime confidante and now-sister-in-law Corinne Roosevelt and came to instead rely for the companionship of her own now-aging childhood nursemaid. According to the letters of family members, her most prominent character trait was a remote indifference towards others and it conflicted with Theodore Roosevelt’s exuberant extroverted nature, which drew others to their home and proved beneficial as he entered politics. Nevertheless, she had a marked ability to control him with merely a look or gesture and also ensure her own necessary solitude. She also joined him in outdoor sporting activities, learning to play tennis, swim long-distance, bicycle, and row, also becoming an expert horsewoman.

When her husband was appointed one of three Civil Service Commissioners (1889-1894), by President Benjamin Harrison,. Edith Roosevelt established households in the first of two homes they would maintain while he held the position. There she began to avidly pursue cultural interests, attending concerts, visiting museums and closely befriending the elderly historian and social critic Henry Adams, joining his select salon and relishing the intellectual stimulation she found there. She made her first visit to the White House, calling at the 1890 New Year’s Day Reception and would first be a dinner guest there of President Grover Cleveland and First Lady Frances Cleveland in 1894. During this period, she also made her first trip to the western U.S., visiting her husband’s Dakota ranch with him and also Yellowstone Park, as well as to the Chicago World’s Fair. Spending the summer months at their Sagamore Hill home, Edith Roosevelt was able to well-discipline her maturing children without raising her voice; encouraged by their father, they also began to accumulate a large menagerie of all types of animal pets.

Edith Roosevelt expertly managed the family’s finances through the difficult early 1890s, a time of economic uncertainty. Her strenuous protest against his running for Mayor of New York in 1894 proved so influential that Theodore Roosevelt acquiesced, though the compromise of this great ambition of his left him frustrated, a fact over which she later suffered great remorse.

When her husband was appointed as a New York City Police Commissioner (1895-1897), Edith Roosevelt relocated her family there from Washington, D.C. Despite her pride in his earning a national reputation by enforcing unpopular laws against the sale of alcoholic beverages and prostitution and confronting bribery and corruption, she was happy to return to the national capital in 1897 when he was made Assistant Secretary of the Navy (1897-1898),. Making a strong case to the President to declare war on Spain for tyrannical hold on Cuba and mistreatments against its people, Roosevelt also overtly declared his ambition for military glory, telling McKinley that enlisting in the military was a decision he would not first make after consulting his then-pregnant wife.

Despite the fact that Edith Roosevelt was still recuperating from surgery of an abdominal tumor which had nearly killed her, Theodore Roosevelt resigned his government position and enlisted in the U.S. Army, following the April 1898 declaration of the Spanish-American War. Edith Roosevelt entirely supported his decision to accept a War Department commission as the Lieutenant Colonel of a cavalry troop to become popularly known as the “Rough Riders.” Years later, Roosevelt admitted to a military aide that he “would have turned from my wife’s deathbed” to do so. Before the Rough Riders departed for Cuba, Edith Roosevelt travelled to meet her husband and his troops at Tampa Bay. She followed their progress in Cuba through the newspapers and when they returned to encampments at Montauk, Long Island, she managed to break a malaria quarantine to be among them by volunteering as a Red Cross nurse.

Edith Roosevelt had faint hope that, having achieving national fame with the Rough Riders, her husband would settle into a literary life with her. She especially despised the press who she dubbed “fiends” because she felt the media violated her personal privacy. Just two months after his return from Cuba, when her popular husband was unanimously nominated as the Republican candidate for Governor of New York, she eagerly began to attend public events with him, making an especially prominent appearance at the launch of his campaign at Carnegie Hall. Her most important public role, however, was in assuming control of his public correspondence, dictating responses with answers and in a tone that matched his own and reflected well on him as a political candidate

Following his election and 1899 gubernatorial inauguration, Edith Roosevelt moved her family into the Victorian governor’s mansion, where she focused on the education and care of her young children as well as hosting the conventional receptions expected of a governor. Finding comfort in having her family settled in Albany and also living without housing expense and being able to save her husband’s entire salary, Edith Roosevelt made clear her opposition to the growing movement to draft him on the 1900 Republican presidential ticket as President McKinley’s vice presidential running mate. She nevertheless insisted on attending the party’s national convention that year, her first, and watched with reluctance as he was nominated.

CAMPAIGN AND INAUGURATION:

Edith Roosevelt took no public role during her husband’s successful 1900 vice presidential campaign but was a prominent figure at the 1901 Inauguration ceremonies. She returned with her children to New York the next morning, not intending to settle them all in Washington until the following year. Six months later, McKinley was assassinated, Roosevelt assumed the presidency and she was thrust into the role of First Lady.

As the incumbent First Lady at the time of her husband’s 1904 nomination for the presidency, Edith Roosevelt played no public role. During the traditional “Notification Day” ceremony when he received official notice of his nomination as the Republican presidential candidate and accepted it on the porch of their Sagamore Hill home, for example, she remained unseen but listening behind a screen at an open window. At the 1905 Inauguration Ball, she wore an American-made pale blue gown with a gold medallion pattern.

FIRST LADY:

40 years old

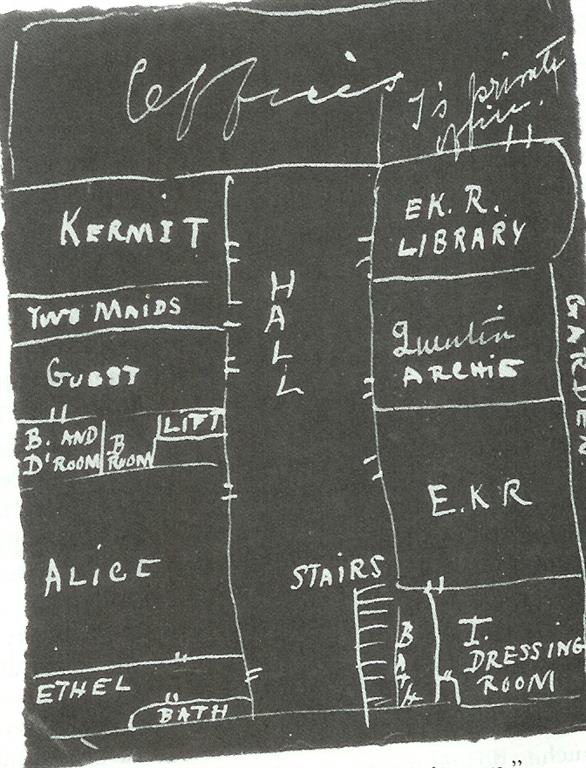

14 September 1901 – 4 March 1909

Edith Roosevelt’s first order of business as First Lady was to adapt the limited space appropriated for the family living quarters to her own large family. Since this was located at the western end of the second floor where the executive offices were also located, at the eastern end, she had great motivation in approving the tremendous structural change which took place at the Executive Mansion, which her husband officially changed to “the White House.” The greatest shift in life resulting from these renovations of 1902 was the creation of a West Wing to house the executive staff offices, thus making the second floor entirely the private domain of the family. New woodwork and lighting, a plumbing and heating system were also added.

Having had an interest in the White House and having known Frances Cleveland,. Edith Roosevelt did not view the mansion as merely the home of her family but the representation of the nation. Edith Roosevelt worked with her husband in guiding the symbolic look of the public state rooms, matching the new status of the United States on the world stage as a leading power.

The clutter of homey Victorian touches were removed; walls were redesigned with the simple classical feature of columns, the size of chandeliers reduced, and the state rooms furnished in “colonial revival” to reflect a stylized version of the American nation’s origins. In addition, it was Edith Roosevelt who determined that tourists coming into the house through the newly structured East Wing should also value the role of First Ladies in American history and had not only the hall lined with the few portraits of presidential wives and hostesses then in the White House collection but also the various dinner service plates which had been used in past Administrations. As visitors entered through the East Collonade, they also passed a new “Colonial Garden” which she had landscaped. The First Lady worked directly with the architectural firm McKim, Mead and White which conducted the renovation, and they sought her approval in every phase. She also regularly reviewed the budget against use of the half-million dollar congressional appropriation for the renovation. The clutter of homey Victorian touches were removed; walls were redesigned with the simple classical feature of columns, the size of chandeliers reduced, and the state rooms furnished in “colonial revival” to reflect a stylized version of the American nation’s origins. In addition, it was Edith Roosevelt who determined that tourists coming into the house through the newly structured East Wing should also value the role of First Ladies in American history and had not only the hall lined with the few portraits of presidential wives and hostesses then in the White House collection but also the various dinner service plates which had been used in past Administrations. As visitors entered through the East Collonade, they also passed a new “Colonial Garden” which she had landscaped. The First Lady worked directly with the architectural firm McKim, Mead and White which conducted the renovation, and they sought her approval in every phase. She also regularly reviewed the budget against use of the half-million dollar congressional appropriation for the renovation.

In order to streamline and bring order to the entertaining schedule and the guests invited to the White House, Edith Roosevelt hired the first federally-salaried White House Social Secretary, Isabelle Hagner. Previous First Ladies had depended on family members (Julia Tyler’s sister Margaret Gardiner), close friends (Frances Cleveland’s former schoolmate), hired a private secretary (Lucy Hayes) or depended on executive staff (Ida McKinley relied on her husband’s assistant private secretary George Cortelyou).

Edith Roosevelt hosted not only the traditional schedule of winter and spring formal dinners, the special dinners held to honoring visiting heads of state, the larger, general receptions and the innovative afternoon musicals she hosted. These were especially noteworthy, for among the composers and musicians were Ignace Jan Paderewski and Pablo Casals.

More than any aspect of being First Lady, Edith Roosevelt despised having her privacy and family life exposed to the public through the press. She steadfastly refused to grant interviews to reporters and even resisted having her clothing described for press stories of what she wore to public events. In fact, she often wore the same outfit but it was ingeniously described in different ways to suggest that she had a larger trousseau than she did. Edith Roosevelt’s one concession to the press was to have her children pose for the city’s renowned photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston, often with many of their beloved animal companions, and publicly release these for use in newspapers and magazines, there being a voracious public interest in the presidential children More than any aspect of being First Lady, Edith Roosevelt despised having her privacy and family life exposed to the public through the press. She steadfastly refused to grant interviews to reporters and even resisted having her clothing described for press stories of what she wore to public events. In fact, she often wore the same outfit but it was ingeniously described in different ways to suggest that she had a larger trousseau than she did. Edith Roosevelt’s one concession to the press was to have her children pose for the city’s renowned photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston, often with many of their beloved animal companions, and publicly release these for use in newspapers and magazines, there being a voracious public interest in the presidential children

Overseeing the educations of her maturing children, the youngest of whom lived full-time at the White House in the early part of the Administration, Edith Roosevelt also attempted to manage the lifestyle of her stepdaughter Alice, who became a public figure in her own right. In December of 1901, Alice Roosevelt was given a reception to introduce her formally into high society as a debutante. Two months later, it was she and not the First Lady who was given the honor of dedicating theMeteor,the yacht of German Prince Heinrich, brother of the Kaiser, then visiting the United States to strengthen ties between the two nations. Overseeing the educations of her maturing children, the youngest of whom lived full-time at the White House in the early part of the Administration, Edith Roosevelt also attempted to manage the lifestyle of her stepdaughter Alice, who became a public figure in her own right. In December of 1901, Alice Roosevelt was given a reception to introduce her formally into high society as a debutante. Two months later, it was she and not the First Lady who was given the honor of dedicating theMeteor,the yacht of German Prince Heinrich, brother of the Kaiser, then visiting the United States to strengthen ties between the two nations.

Seeking to define for the public just what the role of this president’s daughter was, the press dubbed her “Princess Alice” and the unofficial title remained with her through life. Edith Roosevelt oversaw the February 1906 White House wedding of her stepdaughter to Ohio Congressman Nicholas Longworth, and also offered use of the White House to her husband’s niece Eleanor Roosevelt for her marriage to distant cousin Franklin Roosevelt, but the couple chose to instead marry in private, in New York. As a wedding gift to the Franklin Roosevelts, Edith Roosevelt gave a small watercolor that had originally been a gift to the President, which she did not like.

Edith Roosevelt also played a limited but important political role as First Lady. Unlike her immediate predecessors Lucy Hayes, Frances Cleveland, Caroline Harrison and Ida McKinley, for example, she did not join the President on his transcontinental public train trips to the western part of the country. She did make an official trip with him to Georgia and to the Panama Canal, then under construction.

As First Lady, Edith Roosevelt adopted no specific constituency or public welfare issue. Although her correspondence reflected the demeaning terminology of the era’s white, elite class for those who were non-white and working-class, documentation shows that she consistently maintained her private charitable donations to those citizens who, beset by illness or unemployment, were in dire need. Besides her regular contributory support for the Washington Hospital for Foundlings, the Hope and Health Mission, Children’s Hospital and the Washington Home for Incurables, her secretary recalled that the First Lady most frequently sent large gifts of cash to various free hospitals that treated the poor, instructing physicians to hand out cash sums to those being discharged.

Edith Roosevelt’s most important role in policy was to serve as a conduit between their trusted friend, Cecil Spring-Rice, a British government representative whose junior status prevented his being appointed the official Ambassador to the U.S. It focused largely on the deteriorating relationship between Japan and Russia. Spring-Rice was able to privately exchange information about the conflict with the President by writing to the First Lady at the White House, thus making the correspondence entirely private, but which she then passed on to her husband. One of Theodore Roosevelt’s greatest accomplishments was negotiating the Russo-Japanese War, for which he was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize in 1906

While she continued to detest newspaper publicity about herself, Edith Roosevelt did begin to make more public appearances with the President as her children matured and grew more independent of her towards the end of the Administration.

The First Lady later admitted that she was distracted on Election Night 1904 when Theodore Roosevelt pledged to the press that, having won a full four-year term, he would not seek another term in 1908. Edith Roosevelt said that had she known he intended to state this, she would have prevented him from doing so – not because she wished for another four years in the White House but because she realized it weakened his negotiating power in initiating legislation with Congress.

She also never lost a fear of harm coming to the President, conscious of the threats made by anarchists at the time to the lives of many world leaders. When she found and appropriated a small cottage in Albemarle County, Virginia for use as a presidential weekend retreat, Edith Roosevelt instructed a Secret Service agent to guard the President there from a distance, and without his knowledge.

LIFE AFTER THE WHITE HOUSE:

A year after leaving the White House Edith Roosevelt joined members of her family in an overseas trip, remaining largely in Italy but also going to Egypt where she rode a camel. In 1911, she suffered a severe concussion which permanently robbed her sense of smell.

Edith Roosevelt was not in accord with her husband’s growing disdain for his hand-chosen successor William Howard Taft and his shift towards views aligned with the growing Progressive Party movement; nor did she encourage his unprecedented 1912 attempt as a former president to again be nominated for the presidency. She nevertheless accompanied the former President to the 1912 Republican convention in Chicago and played a significant role in helping to edit his defining speech to progressive supporters at a rally outside of the convention, insisting that he remove rancorous and angry language, which proved helpful to his higher cause.

Nevertheless, the split of the Republican Party, as led by Roosevelt who pursued the presidency as a third-party candidate, left the former First Lady disgusted and upset. She was in New York when she learned that her husband had been shot at a rally in Chicago. Going to his side, she immediately took charge of his hospital care and recuperation, forbidding the presence of all those clamoring to meet with him on political matters, except for his vice presidential candidate and the reform leader and suffragist Jane Addams.

In 1913, she accompanied the former President to South America for the first leg of his famous trip exploring the Amazon River and made her first visits to Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina and Chile. In 1916, she joined the former President in his staunch opposition to the re-election of the Democratic President Woodrow Wilson, whom she described as a “vile and hypocritical charlatan.” Her views on Wilson’s refusal to permit Roosevelt to lead a division of American troops into the European war, once the U.S. formally entered it in 1917 are unknown, but considering that the decision was based on her husband’s deteriorating health, it can be surmised that she may have been relieved by it

Edith Roosevelt seemed to more philosophically accept the July 1918 death of their youngest son Quentin, shot down in their plane during World War I and the wounds which war inflicted upon their sons Ted and Archie. She resisted giving in to depression, remaining physical active by swimming and row-boating. The former President, however, already beset by rheumatoid arthritis contracted by a fever during his exploration of the Amazon River, was shaken. He died suddenly of a heart attack in his sleep six months later.

Edith Roosevelt did not attend her husband’s funeral but remained in private at their home. Two days later, she left the place for a visit with her sister-in-law and then left for France, where she visited her son’s grave and made arrangements for placement of a memorial fountain at his burial place, and settled in Italy where she lived with her sister for two months and studied the language.

Later in 1919, Edith Roosevelt was awarded the free franking privilege and a $5000 presidential widow’s pension from Congress and, in addition, accepted the offer of a $5000 pension from philanthropist Andrew Carnegie because, she claimed, to not do so might cause him to withdraw the offer and it could adversely affect her fellow former First Ladies who were also recipients. She used a percentage of the pension to fund her personal care for many struggling members of the surviving Rough Riders and a decade-long patronage of poet Elbert Newton, to whom she became quite close.

In September of 1920, Edith Roosevelt wrote her first public foray into partisan politics by writing an endorsement for Republican presidential candidate Warren G. Harding in The Woman-Republican, a party newsletter overseen by Corinne Roosevelt Robinson in her role as an officer of the Women’s National Republican League. Although she had not been an advocate for women’s suffrage, once it was a foregone conclusion, she spoke out on the civic responsibility of women to learn the issues and to vote. She voiced support for the Harding Administration out of loyalty to her son Ted, who the President named as Assistant Navy Secretary. Her lack of a public statement for Coolidge in 1924, however, did not indicate that she opposed the incumbent’s candidacy, only that there was no especial benefit to members of her family in his Administration

Edith Roosevelt did not regularly imbibe of alcoholic beverages outside of an occasional glass of wine, During the one dozen years that Prohibition was enforced, however, the former First Lady made her personal opinion clear that she considered it a violation of personal liberty, according to her stepdaughter Alice Longworth, by serving cocktails of hard liquor to guests at Sagamore Hill.

Edith Roosevelt’s natural literary ability emerged in her role as the editor of her family papers, aided by her son Kermit, published by Scribner’s asAmerican Backlogs(1928). Believing that women who chose to be mothers may feel they sacrificed the best time of their life, she used her experiences as an active widow to encourage others to do likewise, while still healthy and vital. She visited In December of 1919, she voyaged to Argentina, Chile and Brazil with her son Kermit and explored the sites of Rio de Janeiro by public street cars (1919), British Guiana (1921), France, Germany, England and South Africa (1922), Brazil (1923 and 1927), Hawaii, Japan, China, and Russia, including the six-thousand mile trans-Siberian railway trip (1924), Sicily and Malta (1925), Mexico’s Mayan ruins (1926), Panama, Guatemala and San Salvador (1928), Puerto Rico and Haiti (1930), Jamaica (1931) and the Philippines (1933). She referenced many of her travels as a contributing writer to a published travel book,Cleared for Strange Ports(1927), her fellow authors being her son Kermit, his wife and her son-in-law, the husband of her daughter Ethel

In 1927, she purchased her maternal great-grandfather’s home as her own summer place in Brooklyn, Connecticut, calling it “Mortlake Manor,” as a getaway from her children and grandchildren. Claiming she became depressed at the sight of her disabled sister-in-law Anna who was confined to a wheelchair, the two sisters of Theodore Roosevelt, her old friends, were kept at a new and further distance. “Edith Roosevelt has in a snarkish mood ‘silently vanished away,’” Anna wrote to Corinne.

When it came to memorial efforts on behalf of her husband, Edith Roosevelt tended to favor restraint, not encouraging the building of an impressive memorial to him on land purchased on the Potomac River and named “Roosevelt Island,” to honor him, and critical of even a Pulitzer-prize winning biography of him. Determined to maintain certain aspects of their marriage permanently private, she also burned a substantial percentage of their correspondence.

When the re-election of incumbent Republican President Herbert Hoover was challenged in 1932 by the New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt, husband of Edith Roosevelt’s niece-by-marriage, the former First Lady began to receive hundreds of letters and telegrams which mistakenly identified her as F.D.R.’s mother or even wife. While she did privately support Republican Hoover, it was this public misunderstanding of the relationship between Franklin Roosevelt and her late husband Theodore Roosevelt which led her to make her only return visit to the White House, on 11 August 1932, and join President Hoover at his Notification Day ceremonies and to make one of the most overtly political gestures yet by a former First Lady, addressing a massive 31 October 1932 Madison Square Garden rally for Hoover and carried by radio.

Edith Roosevelt would also make a public radio speech on 16 September 1935 for the National Conference of Republican Women and further appeared in a newsreel with Mrs. Hoover in the effort to reduce the death rate of women following childbirth. Although it was Lou Hoover who became the first incumbent First Lady to have the sound of her voice recorded and preserved, Edith Roosevelt was the chronologically earliest to do so.

At a 1921 family wedding, the former First Lady had encountered Franklin D. Roosevelt and judged his loud behavior during the event to be inappropriate. During his presidential compaign, she so tired of receiving letters congratulating her on the assumption she was either his morther or an aunt that she purchased pro-Hoover envelopes in which to send her response, claiming there was only the slightest connection between her late husband and the Democratic candidate, yet failing to honestly share the fact that FDR's wife was her late husband's niece.

Once he was elected President, however, she kept an open mind that his elements of his proposed New Deal reforms would eventually improve the devastated economy. She did not criticize her activist niece, the First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, in either public print or private correspondence, and kept in touch with her by letter.

Despite their being middle-aged, Edith Roosevelt’s three remaining sons enlisted for military service with the outbreak of World War II, Kermit with the British Army. When his worsening alcoholism led to dismissal from the British Army, the American President found a post for his distant cousin with the U.S. Army in Alaska. He committed suicide there with a revolver in 1943 but Edith Roosevelt was told that he died of a heart attack. A year later her son, fifty-six year old Ted, the eldest to fight in the D Day invasion, also died of a heart attack. She suffered remorse for the rest of her life following the death of her sole sibling Emily Carow, whom she had systematically alienated and distanced.

Having grown to respect her distant cousin President Franklin D. Roosevelt, his 1945 death shocked her and she contacted her widowed niece with sympathy. Although she remained a registered Republican, she declared Harry Truman to be a President with intelligence and tact.” Over the next three years she lost some lucidity.

DEATH:

30 September 1948

Oyster Bay, New York

BURIAL:

Young’s Cemetery

Oyster Bay, New York

ALICE HATHAWAY LEE ROOSEVELT

BORN:

29 July 1861

Brookline, Massachusetts

FATHER:

George Cabot Lee, banker (21 March 1830 – 21 March 1910) a banker and founding partner of the brokerage firm Lee, Higginson & Company,

MOTHER:

Caroline Watts Haskell (27 January 1835 – 14 January 1914). She married George Lee on 10 December 1857, Boston, Massachusetts. Despite the fact that seventeen years had passed from the time her daughter Alice, the first wife of Theodore Roosevelt, until he became President, Mrs. Lee remained on good terms with Roosevelt. This was even in spite of the fact that he refused to ever again verbally acknowledge the existence of his first wife, so devastating was her death to him.

SIBLINGS

Second of six children; four sisters, one brother: Rose Lee [Gray] (1860-?), Harriet Lee Payne [Hammond] (1863-?); Caroline Haskell Lee [Fessenden] ((1866-?, Isabella Mason [Mumford] (1869-?), George Cabot Lee, Jr. (1871-?)

ANCESTRY

English

RELIGION

Unitarian

EDUCATION

To date, nothing can be learned about the formal education of Alice Hathaway Lee Roosevelt. One account described it simply as “conventional and fashionable.” There is no evidence that she boarded away from home to attend school as many other young women of the upper-class had begun to do by the time of her youth, but rather likely attended a local, private school.

LIFE BEFORE MARRIAGE

Although little is known about the life of Alice Hathaway Lee before her marriage to Theodore Roosevelt, a general profile is suggested by several known facts. She was unusually athletic for a woman of her class and era, an avid tennis player and hiker, who also enjoyed bird-watching in natural settings and winter sports such as bobsledding,

Based on the recollections of her only child later in life, Alice Lee’s social life was largely confined to the close friendships she formed with her elder and immediately younger sister, Rose and Harriet, who were close to her own age, although the two younger sisters Caroline and Isabella also joined their ranks as they aged.

Through ancestry and inter-marriages, Alice Lee’s family connections included members of Boston’s most powerful and wealthy clans, notably the Cabot and Saltonstall families. Her father’s success in banking was evidenced by the family’s unusually large home, a three-story mansion in the Chesnut Hill section of Brookline, Massachusetts.

Alice Lee met Theodore Roosevelt on 18, October 1878 through her cousins Richard and Rose Saltonstall of Boston, neighbors who befriended the Harvard student. He spent his October birthday with her that year and began to visit the 17 year old at the home of her family. Falling in love with her over Thanksgiving weekend, which they both spent with the Saltonstalls, Theodore Roosevelt determined to marry Alice Lee that weekend. Despite his continuing romantic friendship with Edith Carow, Roosevelt proposed marriage to Alice Lee in the summer of 1879. She initially turned him down, but a month after her December society debut, she accepted his proposal on 25 January 1880.

Before the engagement was publicly announced on 14 February 1880, Theodore Roosevelt wrote to Edith Carow and told her of his plan to marry Alice Lee. Although Edith Carow did not commit to paper her reaction, naturally shocked reaction, members of the Roosevelt family specifically recalled her being shocked by it. Nevertheless, Edith Carow hosted a dinner party in honor of Roosevelt and attended the Roosevelt-Lee wedding where she danced vigorously

MARRIAGE:

19 years old, to Theodore Roosevelt. Columbia University Law School student, (born 27 October 1858, New York, New York) on 26 October 1880, Brookline Unitarian Church, Brookline, Massachusetts)

CHILDREN:

1 daughter; Alice Lee Roosevelt [Longworth] (12 February 1884 – 20 February 1980)

LIFE AFTER MARRIAGE:

Following a two-week honeymoon at the Roosevelt family’s Oyster Bay home, Alice Roosevelt moved into the West 57thStreet home in New York City of her new husband, where he lived with his widowed mother, two sisters and brother. She began taking classes in Drina Potter’s Tennis School and regularly hosted small weekly receptions for friends on Tuesday afternoons. While welcomed into her new husband’s circle of friends and family, she distinctly noted the remote unfriendliness towards her from Edith Carow. Despite this, both women shared many social events, jointly attending art shows, the theater, dinner parties and balls, even travelling together with Roosevelt’s sister Corinne. Alice Roosevelt would also attend the funeral of Edith Carow’s father, in March of 1883. Later that year, Edith Carow would attend the wedding of Roosevelt’s brother Elliott to Anna Hall (the parents of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt).

Alice Roosevelt, noted for her physical beauty and athleticism, made a marked impression on the elite class of New York at the exclusive events held during the 1880-1881 social season, notably the social debut of her sister-in-law Corinne Roosevelt. Edith Carow, sometimes in attendance at these events, increasingly receded from the social whirl, although she still held Theodore Roosevelt as her romantic and intellectual ideal and somehow, according to a granddaughter, believed she would someday, somehow be married to him. When Alice Roosevelt made a trip to visit her parents in the spring of 1881, her husband immediately called on his friend Edith Carow, taking her for a carriage ride.

In the summer of 1881, Alice and Theodore Roosevelt left for a four-month trip to Europe, including visits to Switzerland, France, Italy and England. Upon their return from Europe, he successfully pursued his first political position, being elected to represent the state’s 21stdistrict in the New York State Assembly. To celebrate his victory, Edith Carow hosted a party, attended by Alice Roosevelt. The couple moved to Albany with the intention of purchasing a nearby farm. The young Mrs. Roosevelt, however, did not enjoy the isolated life there. Following her husband’s election to a second one-year term, she decided to live in New York, where they bought a home at 55 West Forty-Fifth Street and to which he returned on weekends.

Alice Roosevelt became close to her mother-in-law and sisters-in-law Anna and Corinne. She also became active in several charitable organizations, making visits to the patients being cared for at the hospital ward underwritten by her late father-in-law and participating in a program which provided ice cream in the summers to the young boys of who delivered newspapers to provide income for their working-class families.

Alice Roosevelt became pregnant with their first child in the spring of 1883; shortly afterwards, Theodore Roosevelt purchased several dozen acres of property near the summer home of his youth, in Oyster Bay, Long Island, and began building a large wood home there he called “Leeholm.”

Theodore Roosevelt was in Albany on February 12, 1884 when Alice Roosevelt gave birth that day to their first child, a daughter with the same name. A subsequent telegram, however, summoned him back to New York immediately. Upon his return, he learned not only that, just hours after childbirth, his wife was dying of a kidney disease but that his mother was dying of typhoid fever. His mother died at 3 a.m. and his wife died at 2 p.m.

New York Governor Grover Cleveland, who would be elected President of the United States nine months later, was among those who wrote a sympathy letter to Assemblyman Roosevelt upon hearing of his tragic double-loss. Edith Carow was among those who attended the double-funeral.

DEATH:

14 February 1884

New York, New York

BURIAL:

Greenwood Cemetery

Brooklyn, New York

|