|

Copyright, Attention: This website and its contents contain intellectual property copyright materials and works belonging to the National First Ladies’ Library and Historic Site and to other third parties. Please do not plagiarize. If you use a direct quote from our website please cite your reference and provide a link back to the source.

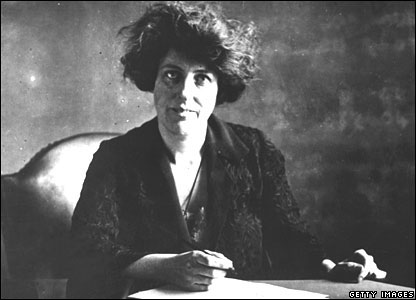

First Lady Biography: Ellen Wilson

ELLEN LOUISE AXSON WILSON

Born:

15 May, 1860

Savannah, Georgia

Ellen Louise Axson was named after two aunts and born in the home of her paternal grandparents.

Father: Father:

Samuel Edward Axson, was born 23 December 1836, in Waltourville, Georgia. In 1856, he enrolled at Oglethorpe College, to study for the ministry, and was ordained in 1859, assigned to the pastorate of Beech Island, South Carolina, a year after his marriage and a year before the birth of his daughter Ellen. Axson was the pastor of the First Presbyterian Church in Rome, Georgia.

Edward Axson served in the Confederate Army as the First Regiment, Georgia Infantry chaplain from 1861 to 1863. He then assumed the Presbyterian Church pastorate of Madison, Georgia, relocating his family there and also serving as a teacher for the town’s children in a private school created by the community with classes being held in the Axson home.

Just after the Civil War ended, Axson accepted the pastorate of the First Presbyterian Church in Rome, Georgia, which had been decimated during the war and faced the challenge of rebuilding. Just prior to the death of his wife in 1881, Axson suffered a nervous collapse, the first in a series of mental health problems that would trouble him for the rest of his life. He was hospitalized at a mental health facility the following year and died two years later on 28 May 1884. All evidence suggests that he committed suicide. Just after the Civil War ended, Axson accepted the pastorate of the First Presbyterian Church in Rome, Georgia, which had been decimated during the war and faced the challenge of rebuilding. Just prior to the death of his wife in 1881, Axson suffered a nervous collapse, the first in a series of mental health problems that would trouble him for the rest of his life. He was hospitalized at a mental health facility the following year and died two years later on 28 May 1884. All evidence suggests that he committed suicide.

Mother:

Margaret Jane Hoyt Axson was born 8 September, 1838, in Athens, Georgia. The last of six children, she was educated well at the Greensboro Female College in Greensboro, Georgia. Enrolled there from 1853 to 1856, she won numerous academic awards and developed a voracious reading habit.

Following her graduation, Janie Hoyt Axson took a job at the college, working there for two years as a teacher. She is one of the earliest known examples of a First Lady’s mother who was professionally employed prior to her marriage. Janie Hoyt (as she was known) married Edward Axson (as he was known) at the First Presbyterian Church, Athens, Georgia in 1858 in a ceremony over which both of their fathers presided.

Herself a rapid consumer of all forms of literature, she inculcated her daughter Ellen with a similar passion of reading, both for pleasure and research. She died on 1 November 1881, shortly after giving birth to her fourth child Herself a rapid consumer of all forms of literature, she inculcated her daughter Ellen with a similar passion of reading, both for pleasure and research. She died on 1 November 1881, shortly after giving birth to her fourth child

Ancestry:

English. The patriarchal line of her father’s family originated in England but settled in Bermuda. In 1684, they migrated from Bermuda to South Carolina. Despite her close public identity with the South, three of Ellen Wilson’s grandparents were from the North. Her father’s mother Rebecca Randolph was from a Princeton, New Jersey family. The family of her mother’s father was from Somerset, England, her immigrant ancestor John Hoyt settling in Salem, Massachusetts nine years after the Pilgrims established Plymouth, the first in what became Massachusetts Bay Colony. Her great-great grandfather fought in the French and Indian Wars and helped capture Fort Ticonderoga from British troops in 1775, as part of the famous “Green Mountain Boys,” led by Ethan Allen. Ellen Wilson’s maternal grandfather was born in Gilmanton, New Hampshire and her maternal grandmother in Springfield, Massachusetts.

Religion:

Presbyterian. Ellen Wilson’s father and both grandfathers were Presbyterian ministers.

Siblings:

Ellen Wilson was the first-born of four children, two brothers, one sister: Isaac Stockton Keith Axson (6 June 1867 – 26 February 1935), Edward Williams Axson (1876- 26 April 1905), Margaret Randolph Axson [Elliott] (10 October 1881 – 24 May 1958)

Education: Education:

The Madison Male and Female Academy, Madison, Georgia (1864-1865). Pre-school. Ellen Wilson appears to be the first First Lady to have received a formal pre-school education. Established by her parents in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, with classes conducted in their Porter Street home, Ellen Wilson was only four years old at the time her formal education began.

The Sabbath School, Rome, Georgia (1865-1871), grammar and middle school.

Little is known of the nature of this school or its academic training, other than that students also received religious training. Since its foundation and teaching was part of the church work being managed by her father, as well as the fact that her mother was an experienced educator, and that she graduated in 1871 with “satisfactory evidence of knowledge and piety,” Ellen Wilson received a rigorous enough education enabling her to proceed on to a more formal institution at the age of eleven.

Rome Female College, Rome, Georgia, (1871-1876), high school.

Biographer Frances Wright Saunders chronicled that Ellen Wilson received an education here in algebra, logic, botany, natural history, philosophy, and geometry, excelled in English literature, composition and French and even taught herself trigonometry. The discipline which proved to have the most profound affect on her, however, was the study of art, beginning with drawing instruction from teacher Helen F. Fairchild, a graduate from the prestigious National Academy of Design in New York.

Following her graduation, Ellen Wilson continued to study art with Fairchild. In 1878, Fairchild submitted a freehand drawing of a “school scene” by Ellen Wilson at the Paris International Exposition, and the work won a bronze medal for excellence. Following her graduation, Ellen Wilson continued to study art with Fairchild. In 1878, Fairchild submitted a freehand drawing of a “school scene” by Ellen Wilson at the Paris International Exposition, and the work won a bronze medal for excellence.

Excelling in proficiency entry exams required in her application to Nashville University’s education department, Ellen Wilson intended to follow her mother’s path, to pursue training and employment as a teacher. Her father, however, was unable to afford the tuition and Ellen Wilson was unable to further her education in Tennessee as hoped.

She continued her education through self-study by pouring through books at the local library and enrolled in post-graduate classes at Rome Female College, studying German, advanced French and continuing to advance in drawing. By the time she was 18 years old, she began earning a substantial income by drawing crayon portraits.

Art Students League, New York, New York (1884-1885), college-level. Following an independent trip to New York in 1881, Ellen Axson had determined to professionally develop her considerable skill as an artist. After being accepted at the Art Students League on the basis of two submissions, she moved to New York, enrolling in several courses and living in a boardinghouse, supporting herself with inheritance from her late father’s estate. She took classes in charcoal portrait-drawing, sketching of students, sculpture drawing, advanced painting and attended weekly lectures on perspective. Her skill earned her a prestigious placement in a specialized sketching class which used nude and draped live models. The school was considered radical for its administration by its students and their gender equality. Art Students League, New York, New York (1884-1885), college-level. Following an independent trip to New York in 1881, Ellen Axson had determined to professionally develop her considerable skill as an artist. After being accepted at the Art Students League on the basis of two submissions, she moved to New York, enrolling in several courses and living in a boardinghouse, supporting herself with inheritance from her late father’s estate. She took classes in charcoal portrait-drawing, sketching of students, sculpture drawing, advanced painting and attended weekly lectures on perspective. Her skill earned her a prestigious placement in a specialized sketching class which used nude and draped live models. The school was considered radical for its administration by its students and their gender equality.

Appearance: Appearance:

Five feet, three inches tall; light brown hair, dark brown eyes

Life before marriage:

Due the danger of living near active war zones during the Civil War, the infant and toddler Ellen Wilson would live in Athens, Savannah and Madison, Georgia all before the age of five. Her first permanent home was a two-family house on West First Street in Rome, Georgia where her family settled for a year in 1865, followed by at least one if not two other homes there. The family finally purchased their first home in 1871, on East Third Street, where Ellen Wilson’s maternal grandmother came to live with them.

From the earliest records of her life, Ellen Wilson displayed ability for scholarship, even dictating to her mother her first letter to her father before the age of three. She was so voracious a reader that her mother grew concerned for her health at times. Her favorite author was George Eliot and she especially was drawn to English literature and American poetry. From the earliest records of her life, Ellen Wilson displayed ability for scholarship, even dictating to her mother her first letter to her father before the age of three. She was so voracious a reader that her mother grew concerned for her health at times. Her favorite author was George Eliot and she especially was drawn to English literature and American poetry.

As she matured into a young adult, Ellen Wilson began expressing views at odds with the views of her parents and religious training about the need for all women to assume the traditional role of wife and mother. While she loved and respected her parents, she also felt free to express her independent opinion on a range of social issues.

Apparently more for her physical attributes than her unusually keen intellect, Ellen Axson had long appealed to a wide variety of young men. At least five young men avidly courted her, one persisting for four years in proposing marriage, another seeking to bring her on a religious missionary assignment to China. She so rigidly refused to even consider marriage as she matured, let alone dating, that her friends nicknamed her “Ellie, the Man Hater.” Among the specific qualities she wrote that she required in a potential marital partner was that he be “intelligent and interesting.” Ellen Wilson also developed a loving but platonic relationship with another young woman, Elizabeth Adams, with whom she shared an intensely emotional correspondence.

Following the nervous breakdown her widowed father endured in 1883, the Axson household broke up, the youngest daughter raised by a maternal aunt, the eldest son in boarding school and Ellen Wilson and her younger brother living in Savannah, Georgia in the home of her paternal grandparents where she had been born.

Ellen Wilson assumed responsibility for closing up her family’s household in Rome, as well as overseeing the hospitalization and continued treatment of her father who, after displaying violent behavior, was committed to the Georgia State Mental Hospital in Milledgeville. She also assumed responsibility for aiding her elderly and infirm grandparents. These self-imposed tasks further deepened her sense that being a caretaker to those in need was her natural lot in life. Ellen Wilson assumed responsibility for closing up her family’s household in Rome, as well as overseeing the hospitalization and continued treatment of her father who, after displaying violent behavior, was committed to the Georgia State Mental Hospital in Milledgeville. She also assumed responsibility for aiding her elderly and infirm grandparents. These self-imposed tasks further deepened her sense that being a caretaker to those in need was her natural lot in life.

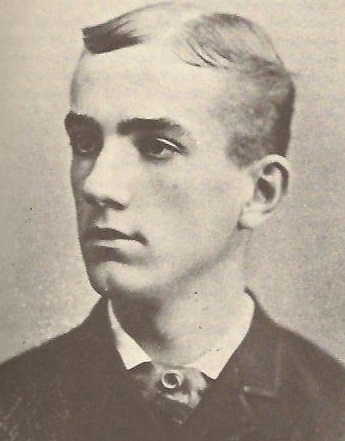

In April of 1883, shortly after the death of her mother, Ellen Axson was attending a church service presided over by her father, wearing a mourning veil. Another congregant, a new attorney visiting from Atlanta, Georgia, couldn’t help staring at her, detecting that she had “lots of life and fun in her.” It was her future husband, Woodrow Wilson.

Like Ellen Axon, Woodrow Wilson also had a father who was a Presbyterian minister, the Reverend Dr. Joseph Ruggles Wilson. The two fathers were, in fact, long-time friends. The attorney used the family acquaintance as an excuse to pay a call at the Axson house. Within a month of their meeting, he penned the first of a lifetime of love letters to her. They shared a mutual acculturation, coming of age in southern states which were part of the Confederacy during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Although born in Virginia, Wilson would also spend his youth in Columbia, South Carolina and Wilmington, North Carolina. Although he attended and graduated from Princeton University in New Jersey, he returned to the South to attend the University of Virginia Law School in Charlottesville, Virginia and first began to practice law in Atlanta, Georgia. Like Ellen Axon, Woodrow Wilson also had a father who was a Presbyterian minister, the Reverend Dr. Joseph Ruggles Wilson. The two fathers were, in fact, long-time friends. The attorney used the family acquaintance as an excuse to pay a call at the Axson house. Within a month of their meeting, he penned the first of a lifetime of love letters to her. They shared a mutual acculturation, coming of age in southern states which were part of the Confederacy during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Although born in Virginia, Wilson would also spend his youth in Columbia, South Carolina and Wilmington, North Carolina. Although he attended and graduated from Princeton University in New Jersey, he returned to the South to attend the University of Virginia Law School in Charlottesville, Virginia and first began to practice law in Atlanta, Georgia.

At the time he began pursuing Ellen Axson, Wilson abandoned his law practice to attend graduate school at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland in preparation for a career in education as a college professor. Within two months of meeting Ellen Axson, Wilson determined to marry her, despite her seeming indifference to him. By what proved to be a propitious but entirely coincidental crossing of paths in September of 1883 at the summer resort town of Morganton, North Carolina, he was able to wear down her resistance and she agreed to marry him. She soon described him to her brother as “the greatest man in the world and the best.” Since he had begun his graduate studies in Baltimore, he sent an engagement ring to her in the mail.

Upon learning that her father had been committed to a hospital for patients with mental health problems, Woodrow Wilson made his way to Ellen Axson’s side in a show of emotional support for his fiancée. With the loss of her father’s income, Ellen Axson assumed financial responsibility for her siblings and began searching for a full-time teaching position. Woodrow Wilson assured Ellen that her two brothers would always be welcome to live in their home as members of their own nuclear family, following their marriage. Ellen Axson offered Wilson the chance to break their engagement, due to the societal shame of what was almost certainly her father’s suicide. He refused.

During her residency in New York City, while studying at the Art Students League, Ellen Axson avidly indulged her free time by regularly visiting the rotating exhibits throughout the city’s network of art galleries. She also became a frequent theater devotee, taking in Shakespearean productions, including three performances by Edwin Booth. She broke polite societal custom by attending lectures around the city at night, without a male escort. Deciding not to wear her engagement ring on a finger which indicated she had promised to marry Wilson, Ellen Axson also indulged in a flirtatious relationship with another man, until he learned of her commitment to marry. During her residency in New York City, while studying at the Art Students League, Ellen Axson avidly indulged her free time by regularly visiting the rotating exhibits throughout the city’s network of art galleries. She also became a frequent theater devotee, taking in Shakespearean productions, including three performances by Edwin Booth. She broke polite societal custom by attending lectures around the city at night, without a male escort. Deciding not to wear her engagement ring on a finger which indicated she had promised to marry Wilson, Ellen Axson also indulged in a flirtatious relationship with another man, until he learned of her commitment to marry.

In defiance of her strict Presbyterian training, she also opened herself up to learning the differences of other faiths, attending Sunday services to hear sermons at not just an Episcopal church but those given at the non-Christian Ethical Culture Society which offered lessons in societal morality without the basis of traditional religious texts. She walked across the new Brooklyn Bridge to hear the famous but controversial preacher Henry Ward Beecher.

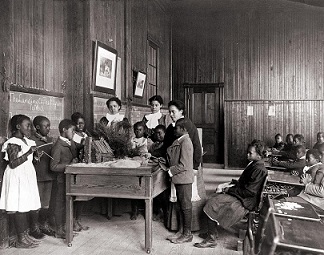

Ellen Axson also began work as a volunteer Sunday school teacher of underprivileged children at the Spring Street Mission School, which worked out of a room above a popular bar with am African-American student body. She expressed the belief that while the work was necessary it would likely prove futile without an effort being made to further encourage their educations at home during the weekdays. Her fiancé also raised mild criticism of this activity, suggesting that it might not be time worthwhile spent and that the location was unsavory for her.

Some evidence suggests that while Ellen Wilson was never a racist in the contemporary understanding of that word, she did believe that the white and black races could never be equal. Her reasoning for this is unclear. She may have been influenced by her father’s view that the destruction of the Confederacy ruined a natural balance which placed the black race in servitude to the white and that the ensuing “sudden and absolute emancipation policy ruined one race and doomed another.” She believed it was her responsibility and that of all white people to ensure that black people were given access to healthy, secure housing and without threat of violence. Some evidence suggests that while Ellen Wilson was never a racist in the contemporary understanding of that word, she did believe that the white and black races could never be equal. Her reasoning for this is unclear. She may have been influenced by her father’s view that the destruction of the Confederacy ruined a natural balance which placed the black race in servitude to the white and that the ensuing “sudden and absolute emancipation policy ruined one race and doomed another.” She believed it was her responsibility and that of all white people to ensure that black people were given access to healthy, secure housing and without threat of violence.

During her stay in New York, Ellen Axson also evidenced her first interest in national politics by subscribing to The Nation magazine, although it “quite exercised” her thinking. It was a topic which also dovetailed with the direction of her future husband’s career. While earning his doctorate at Johns Hopkins University, his first book Congressional Government was published, prompting a frank discussion between them of their individual ambitions for independent careers. When Wilson expressed his interest in pursuing a political career, Ellen announced her intention to focus her energies into his career, a decision she reached entirely without his prompting. Wilson expressed guilt at her sacrificing a promising professional career in art, but Ellen assured him that she retained the option to resume it later in their life together.

Married:

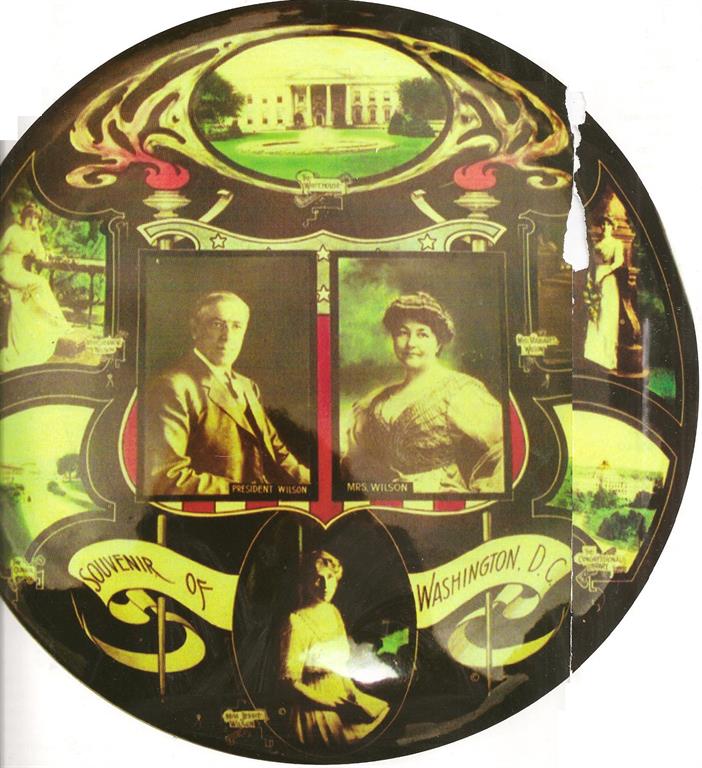

25 years old, on 23 June 1885, Savannah, Georgia, to Thomas Woodrow Wilson (born, 28/29 December 1856, Staunton, Virginia, died 3 February, 1924, Washington, D.C.). Ellen Axson and Woodrow Wilson were married in a ceremony presided over by her paternal grandfather and his father.

Children:

Margaret Woodrow Wilson (16 April 1886 – 12 February 1944), Jessie Woodrow Wilson [Sayre] (27 August 1887 – 15 January 1933), Eleanor “Nell” Wilson [McAdoo] (16 October 1889 – 5 April 1967).

Life after Marriage:

Woodrow Wilson began a teaching stint at Bryn Mawr College in Haverford, Pennsylvania at the time of his marriage. Undertaking work on his second book, one exploring comparative politics, he came to entirely depend on Ellen as a professional partner. In conducting research for his project, she used her considerable skill in German to translate for him complex political, economic and philosophical studies, pamphlets, magazine articles, and books. This level of research also required her to synthesize highly theoretical materials, deepening her intellectual grasp of government and politics. She did this at the same time that she also undertook a home economics class under the tutelage of a Mrs. S.T. Rorer in Philadelphia.

In loyalty to the South of her youth, Ellen Wilson ensured that her first two children were born in her native Georgia. As her own parents had done for her, Ellen Wilson became the first educator to her daughters, teaching them how to read, instructing them in religious training and ensuring a lack of selfishness by presenting all three with one gift each on all of their birthdays. She read them Greek mythology, Shakespeare and hired a nurse who would also teach them German and French. The fact that none of her three children were boys proved to be a tremendous disappointment to Ellen Wilson, a feeling her husband and father-in-law did not discourage. Nonetheless, the semi-permanent household presence of Ellen’s younger brother Eddie gave her husband a sense of having a son. In loyalty to the South of her youth, Ellen Wilson ensured that her first two children were born in her native Georgia. As her own parents had done for her, Ellen Wilson became the first educator to her daughters, teaching them how to read, instructing them in religious training and ensuring a lack of selfishness by presenting all three with one gift each on all of their birthdays. She read them Greek mythology, Shakespeare and hired a nurse who would also teach them German and French. The fact that none of her three children were boys proved to be a tremendous disappointment to Ellen Wilson, a feeling her husband and father-in-law did not discourage. Nonetheless, the semi-permanent household presence of Ellen’s younger brother Eddie gave her husband a sense of having a son.

When Wilson assumed a new position at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, Ellen Wilson became further exposed to differing northern views on public issues. After befriending a Brown University professor, for example, he sent her a book with a more progressive vision of how racial equality could begin to be achieved in the U.S. Following his accepting the offer of Princeton University to chair the political economics department, the family relocated to the college town in New Jersey. In regard to societal norms affecting women, Ellen Wilson affected a more practical and compassionate perspective, assuring her husband’s middle-aged sister for example, that her late-in-life pregnancy was of no shame to the family and that she was welcome to be entertained as an overnight guest in their home.

Part of what Ellen Wilson viewed as her “mission in life” was to embolden her husband’s confidence in his abilities and vision. “It would be hard to say in what part of my life & character you have not been a supreme and beneficial influence,” he wrote her with appreciation for her subtle yet vital role in his professional success. “You are all-powerful in my development.” Still, balancing this role was her continuing streak of independent thinking and behavior. Ellen Wilson attended the 1893 Columbian World’s Fair, held in Chicago, intent on first touring the Women’s Building there. This structure was designed by a woman architect and displayed works of fine art in all forms created by women and it stirred pride and hope within her for the professional recognition and success of artists of her own gender.

Ellen Wilson provided the preliminary architectural renderings of the two-story Tudor-style house in Princeton, which the family then had built and completed in 1896. Along with her study of architecture, her reading subjects ranged from classic and contemporary American, English and French fiction, religion, philosophy, politics, history, and all forms of art. More humorously, when male members of her family once partook of a round of cigars passed to them during a holiday celebration, Ellen Wilson also took one and smoked it, suggesting she had a right to do so if she chose. When a spate of home robberies afflicted the Wilson house neighborhood, Ellen Wilson purchased a gun, learned how to use it and kept it at her bedside during the frequent absences of her husband, in order to be prepared to defend herself, her children and their home.

When her husband vacationed to Scotland and England in the summer of 1896, Ellen Wilson remained home and resumed painting and drawing for the first time in a decade. Using an English landscape and oil of a Madonna in the Princeton University art collection as models, she turned out expert copies, as well as watercolor landscapes and six crayon drawing portraits. She also felt free to travel and explore on her own, once visiting New Orleans to experience its famous Mardi Gras celebration at the pinnacle of its revelry. In New York, she took in a performance of avant-garde actress Alla Nazimova. In 1903, Ellen Wilson made her first trip to Europe, touring England, Scotland, France and Italy with her husband. The following year she returned without him, spending longer periods of time in individual towns and cities of Italy, where she explored works of history and art. When her husband vacationed to Scotland and England in the summer of 1896, Ellen Wilson remained home and resumed painting and drawing for the first time in a decade. Using an English landscape and oil of a Madonna in the Princeton University art collection as models, she turned out expert copies, as well as watercolor landscapes and six crayon drawing portraits. She also felt free to travel and explore on her own, once visiting New Orleans to experience its famous Mardi Gras celebration at the pinnacle of its revelry. In New York, she took in a performance of avant-garde actress Alla Nazimova. In 1903, Ellen Wilson made her first trip to Europe, touring England, Scotland, France and Italy with her husband. The following year she returned without him, spending longer periods of time in individual towns and cities of Italy, where she explored works of history and art.

Ellen Wilson also became involved in the Princeton community. With the retirement there in 1897 of former President Grover Cleveland and former First Lady Frances Cleveland, the Wilsons found they shared not only the same Presbyterian faith and Democratic politics but three young daughters: Ruth Cleveland and Nell Wilson even became good friends. In 1898, Ellen Wilson also helped to form a local women’s organization called the “Present Day Club,” with the purpose of drawing the interest of members into not only artistic Ellen Wilson also became involved in the Princeton community. With the retirement there in 1897 of former President Grover Cleveland and former First Lady Frances Cleveland, the Wilsons found they shared not only the same Presbyterian faith and Democratic politics but three young daughters: Ruth Cleveland and Nell Wilson even became good friends. In 1898, Ellen Wilson also helped to form a local women’s organization called the “Present Day Club,” with the purpose of drawing the interest of members into not only artistic

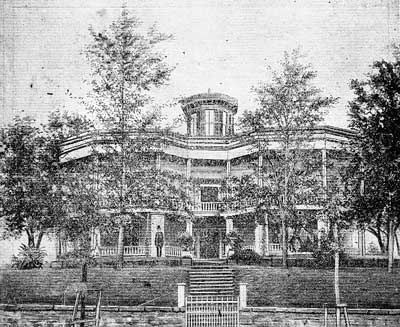

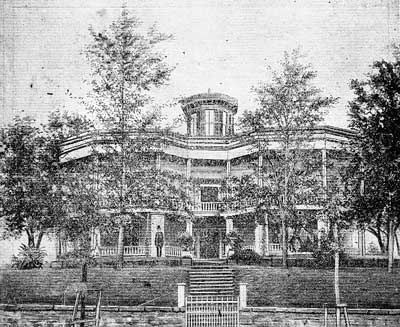

In 1902, Wilson was made president of Princeton University. Ellen Wilson undertook an historic restoration of the mansion provided to the university president and his family as a home, returning its interiors to a look which matched its Florentine style of 1849. Ellen Wilson also designed a breathtaking stained-glass window depicting Aristotle, which was then executed in the famous studios of Louis Comfort Tiffany. She also completely landscaped the grounds in the more informal style of the new century, with rambling flower beds, paths, cedar trees, fountains, sundial, rose garden and pergola. She came to know and entertain there celebrities such as captain of industry J.P. Morgan, author Mark Twain and African-American educator Booker T. Washington. In 1902, Wilson was made president of Princeton University. Ellen Wilson undertook an historic restoration of the mansion provided to the university president and his family as a home, returning its interiors to a look which matched its Florentine style of 1849. Ellen Wilson also designed a breathtaking stained-glass window depicting Aristotle, which was then executed in the famous studios of Louis Comfort Tiffany. She also completely landscaped the grounds in the more informal style of the new century, with rambling flower beds, paths, cedar trees, fountains, sundial, rose garden and pergola. She came to know and entertain there celebrities such as captain of industry J.P. Morgan, author Mark Twain and African-American educator Booker T. Washington.

Among her public activities, Ellen Wilson was a leader among the Princeton University Ladies Auxiliary, a group consisting of both female spouses of faculty and women faculty members. Their accomplishments included installation of a women’s division of the gymnasium and a medical infirmary of the first order, with nurses, maids and eventually a permanent, salaried physician. In her capacity as the university president’s spouse, Ellen Wilson prompted creation of a Princeton student code of honor, following her realization that there was a degree of student cheating occurring on examinations and other forms of testing.

Ellen Wilson also suffered from long bouts of deep depression. She had many personal sorrows in the new century. Her brother Stockton continued to suffer from emotional and physical breakdowns and her other brother, his wife and son drowned in a ferry accident. Despite her strict Presbyterian upbringing and family history of those in the ministry, Ellen Wilson never a conventionally religious person and found little solace in prayer. Instead, she began to search for meaning in the logical-themed writings of German philosophers such as Hegel and Kant. Ellen Wilson also suffered from long bouts of deep depression. She had many personal sorrows in the new century. Her brother Stockton continued to suffer from emotional and physical breakdowns and her other brother, his wife and son drowned in a ferry accident. Despite her strict Presbyterian upbringing and family history of those in the ministry, Ellen Wilson never a conventionally religious person and found little solace in prayer. Instead, she began to search for meaning in the logical-themed writings of German philosophers such as Hegel and Kant.

She also endured what is known to have been an emotional, if not a sexual, affair of her husband with a witty friend Mary Hulbert Peck, a wealthy middle-aged Michigan mother estranged from her husband. Ellen Wilson was well aware of how dependent Wilson could be on the company and approval of women and the extreme loneliness he experienced during their separations.

To counteract this, Ellen Wilson encouraged her husband to “go see some of those bright women….their appreciation of you ought to reassure you…” She surely knew nothing of his passionate letters to her, one of which he opened, “My precious one, my beloved Mary.” Wilson would later confess that his relationship with Mary Peck was “a contemptible error” and “madness of a few months,” which had made him feel “stained and unworthy.” Whether it ever went beyond the emotional and, if so, whether Ellen Wilson was aware of this is unknown. To counteract this, Ellen Wilson encouraged her husband to “go see some of those bright women….their appreciation of you ought to reassure you…” She surely knew nothing of his passionate letters to her, one of which he opened, “My precious one, my beloved Mary.” Wilson would later confess that his relationship with Mary Peck was “a contemptible error” and “madness of a few months,” which had made him feel “stained and unworthy.” Whether it ever went beyond the emotional and, if so, whether Ellen Wilson was aware of this is unknown.

It is known that a primary concern of Ellen Wilson’s in regard to her husband’s relationship with Mary Peck was the potential negative publicity it might someday have on his intended career move into public service. Supportive of her husband’s decision to run as New Jersey’s Democratic gubernatorial candidate in 1910, Ellen Wilson also displayed a natural instinct for the public relations aspects of political life. In her first public exposure through the national media, a profile of the Wilson family in Delineator magazine, her artistic abilities became the primary characteristic by which she was defined for the general public.

During the summer of 1905, Wilson had arranged a respite for their family at an artist’s colony in Old Lyme, Connecticut. Here, Ellen Wilson revived her professional aspirations as a painter. In 1908, while her husband went to Europe, Ellen Wilson returned to Old Lyme, taking instruction in landscape painting. By virtue of her work’s quality, she earned the honor of having her own studio from which to paint. During the summer of 1905, Wilson had arranged a respite for their family at an artist’s colony in Old Lyme, Connecticut. Here, Ellen Wilson revived her professional aspirations as a painter. In 1908, while her husband went to Europe, Ellen Wilson returned to Old Lyme, taking instruction in landscape painting. By virtue of her work’s quality, she earned the honor of having her own studio from which to paint.

It also afforded the future First Lady of the United States familiarity within the circle of artists who would form the core of American Impressionists, among them painter Childe Hassam. Although she now had other interests competing for her time as wife of the New Jersey governor, these sojourns to Old Lyme returned a sense of personal purpose to the life of Ellen Wilson, apart from her identity as a political spouse.

Following her husband’s gubernatorial election, she had the chance to fully develop her earlier interest in politics. Since there was no permanent gubernatorial mansion, Ellen Wilson had minimal social obligations, and used the extra time to focus entirely on the prospect of her husband’s eventual pursuit of the presidency. One great ally she made was Joseph Tumulty, his newly-appointed Irish Catholic private secretary who also functioned as press secretary.

Through Tumulty, Ellen Wilson quickly learned the practical tactics employed in political public relations efforts and he came to discern her as having better political instincts than Wilson. She strongly urged her husband to desist from telling the press that he was not “thinking” about the presidency because, as she said, “it can’t be true,” and would make him vulnerable to accusations of deception. To back up her sensibility on the matter, she brought his attention to a New York Sun editorial which made the same case as she did. On another occasion, it was Ellen Wilson who arranged for the standard-bearer and Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan to meet with Wilson over dinner at their home. In doing this, Ellen Wilson helped secure an important establishment acceptance of Wilson as a serious presidential candidate in 1912. Through Tumulty, Ellen Wilson quickly learned the practical tactics employed in political public relations efforts and he came to discern her as having better political instincts than Wilson. She strongly urged her husband to desist from telling the press that he was not “thinking” about the presidency because, as she said, “it can’t be true,” and would make him vulnerable to accusations of deception. To back up her sensibility on the matter, she brought his attention to a New York Sun editorial which made the same case as she did. On another occasion, it was Ellen Wilson who arranged for the standard-bearer and Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan to meet with Wilson over dinner at their home. In doing this, Ellen Wilson helped secure an important establishment acceptance of Wilson as a serious presidential candidate in 1912.

Although it was an unsalaried and unofficial position, Ellen Wilson was named the chairman of the New Jersey Charities Aid Society.  In that capacity, she made a tour of state institutions supporting veterans, orphaned or delinquent children, those in institutions for the mentally-ill, tuberculosis or with seizures. It gave her a first-hand grasp of the public need for social reform work and the growing sense of responsibility which both state and federal government and private industry were assuming. In that capacity, she made a tour of state institutions supporting veterans, orphaned or delinquent children, those in institutions for the mentally-ill, tuberculosis or with seizures. It gave her a first-hand grasp of the public need for social reform work and the growing sense of responsibility which both state and federal government and private industry were assuming.

Presidential Campaign and Inauguration:

In the months leading up to the Democratic presidential nomination of Woodrow Wilson in 1912, Ellen Wilson’s role in her husband’s campaign assumed greater importance. Before a group in Denver, the candidate personally admitted that it was Ellen Wilson who provided the literary and poetic material which he drew on heavily to artfully make a political point in his speeches, and for which he was being unfairly credited as an unusually poetic politician.

When powerful conservative forces in the Democratic Party used the Louisville Courier-Journal and the New York Sun to express resentment towards the progressivism of Wilson and also suggest he had profited from the Carnegie Foundation unfairly, it was Ellen Wilson who authored a detailed chronicle of events which defended her husband against the charges.

Three months before Wilson won the Democratic presidential nomination at the party convention in Baltimore the week of 25 June 1912, Ellen Wilson joined her husband on a whistlestop campaign speaking tour for numerous stops in her native state of Georgia. Although Mary Bryan had done so with her husband, during his presidential campaign speaking engagements from a train as the 1896 and 1900 Democratic candidate, Ellen Wilson became the first First Lady known to have made such an overtly political appearance in public. Three months before Wilson won the Democratic presidential nomination at the party convention in Baltimore the week of 25 June 1912, Ellen Wilson joined her husband on a whistlestop campaign speaking tour for numerous stops in her native state of Georgia. Although Mary Bryan had done so with her husband, during his presidential campaign speaking engagements from a train as the 1896 and 1900 Democratic candidate, Ellen Wilson became the first First Lady known to have made such an overtly political appearance in public.

As the several days of balloting at the Democratic Convention, House Speaker Champ Clark began to take the lead and increasingly appeared to be the imminent winner of the party’s nomination. On 29 June 1912, Wilson spoke by phone with one of his campaign managers at the convention and authorized withdrawal of his name from the roster of candidates. “You must not do it,” she convinced him. Several days later, through a remarkable forty-six ballots, Wilson won. In her first engaged interaction with the press corps, she admitted that she had feared he would lose the nomination, but expressed confidence that once nominated, he would succeed in the general election.

With the issue of granting women the equal right to vote having become a leading contention between the three 1912 presidential candidates (along with Wilson, there was incumbent Republican President William Howard Taft and former President Theodore Roosevelt), the press corps covering them sought to determine whether Ellen Wilson shared the viewpoint of her husband, who opposed it. The candidate’s spouse refused to publicly express her real views which would conflict with her husband. Ellen Wilson, however, did privately support suffrage. She had become convinced of a women’s right to vote during discussions with her daughter Jessie, a settlement house worker who observed he devastating societal affect of particularly denying poor and working-class women a voice in civic life.

Ellen Wilson spent the duration of the summer and fall of 1912 at the summer home provided to New Jersey’s gubernatorial families in Sea Girt, on the Atlantic coast. During the campaign she took upon herself the personal task of addressing a rumor that she approved of women smoking cigarettes, then a contentious issue. She wrote her own statement of denial and even passed copies of it out to reporters, emphasizing that she believed her intense dislike of the habit might offend those who disagreed with her, even though she had once done so herself in a moment of humor. Unaccustomed to being the focus of national attention, Ellen Wilson sought to cope with the deluge of public mail which she received by hand-writing all her responses. Ellen Wilson spent the duration of the summer and fall of 1912 at the summer home provided to New Jersey’s gubernatorial families in Sea Girt, on the Atlantic coast. During the campaign she took upon herself the personal task of addressing a rumor that she approved of women smoking cigarettes, then a contentious issue. She wrote her own statement of denial and even passed copies of it out to reporters, emphasizing that she believed her intense dislike of the habit might offend those who disagreed with her, even though she had once done so herself in a moment of humor. Unaccustomed to being the focus of national attention, Ellen Wilson sought to cope with the deluge of public mail which she received by hand-writing all her responses.

Following her attendance at a performance of Macbeth, Ellen drew a general analogy to the need for wives to be ambitious in order to help their husbands succeed in attaining their reach for power, though she pointed out that the spouse’s ambition was not for herself personally but out of love and support of their husbands. She also observed that while such drive often came at the cost of a wife’s physical and emotional health, such women would willingly sacrifice their personal well-being rather than be left unsatisfied at the fact that their husband’s failed to capture the pinnacle of power. Perhaps this understanding is what led Ellen Wilson to write to former First Lady Edith Roosevelt, when her husband, then running as the Progressive Party candidate again Wilson, was shot and wounded.

With the Election Day victory of Woodrow Wilson, Ellen Wilson assumed the management of moving them and their three adult daughters from Princeton to Washington, D.C. and taking occupancy of the White House. Ellen Wilson was also honored at a massive Women’s Democratic Club luncheon in New York and she granted several personal interviews with national magazines; the Ladies Home Journal even published two color plate prints of her landscapes. With the Election Day victory of Woodrow Wilson, Ellen Wilson assumed the management of moving them and their three adult daughters from Princeton to Washington, D.C. and taking occupancy of the White House. Ellen Wilson was also honored at a massive Women’s Democratic Club luncheon in New York and she granted several personal interviews with national magazines; the Ladies Home Journal even published two color plate prints of her landscapes.

In preparation for the new Administration, Ellen Wilson consulted with a fashion trend-setter in Princeton on a selection of appropriate clothing. She also played a key political advisory role to her husband, successfully urging him to name William Jennings Bryan as Secretary of State and Joseph Tumulty as White House Press Secretary, despite protest letters from bigots who feared the closeness of a Roman Catholic like him to the President of the United States.

The outgoing First Lady Nellie Taft seemed to have played a significant role in advising her successor on the transition and what her future life in the executive mansion would entail. Following a tradition first set by the outgoing Edith Roosevelt who toured the incoming Nellie Taft through the White House, the latter guided the incoming Ellen Wilson through on 3 March 1913, a day before the Inauguration. The outgoing First Lady Nellie Taft seemed to have played a significant role in advising her successor on the transition and what her future life in the executive mansion would entail. Following a tradition first set by the outgoing Edith Roosevelt who toured the incoming Nellie Taft through the White House, the latter guided the incoming Ellen Wilson through on 3 March 1913, a day before the Inauguration.

Woodrow Wilson read his Inaugural Address to his wife and daughters before he delivered it in public. At the ceremony, wishing to hear him make the speech, the new First Lady arose from her chair to stand beneath the rostrum and look up to watch him and listen, seemingly oblivious to the thousands staring at her.

Although Ellen Wilson had looked forward to the traditional Inaugural Ball, Woodrow Wilson cancelled it as a needless extravagance. She hosted a post-inaugural luncheon, sat watching the Inaugural parade, hosted a large White House dinner for friends and family and then took in a firework display.

First Lady:

4 March 1913 – 6 August 1914

During the transition period following the election and before the inauguration, Ellen Wilson finally turned to her friend and husband’s cousin Helen Bones to aid her as a personal secretary, a role she continued in the White House [see biography of Helen Bones as surrogate First Lady below]. As First Lady, she also rehired Isabelle Hagner to be the Wilson Administration Social Secretary, asking her to repeat the official and federally-salaried position she first originated in 1901 for Edith Roosevelt. Hagner established her working office in the West Sitting Hall, in the family quarters, and it became a central focal point for the President, First Lady and their three adult daughters at the beginning and end of each day. Ellen Wilson made news when she went to a public photographer’s studio to pose for her formal portrait in a gown she had intended to wear to the cancelled Inaugural Ball, rather than request the photographer to capture her seated in the White House; this move symbolized an egalitarian gesture of the new Democratic Administration.

During her first full three months as First Lady, from March until June of 1913, Ellen Wilson hosted over forty White House receptions, with an average guest list of 600. Although both she and the President initially appeared on the receiving lines, it was the new First Lady who endured these to the end, at great expense to her health. As far as the slight derision the press suggested about her sense of fashion style, Ellen Wilson cared little. Bragging that she spent less than one thousand dollars a year on clothes, one newspaper columnist added sarcastically, “and she looks it.” During her first full three months as First Lady, from March until June of 1913, Ellen Wilson hosted over forty White House receptions, with an average guest list of 600. Although both she and the President initially appeared on the receiving lines, it was the new First Lady who endured these to the end, at great expense to her health. As far as the slight derision the press suggested about her sense of fashion style, Ellen Wilson cared little. Bragging that she spent less than one thousand dollars a year on clothes, one newspaper columnist added sarcastically, “and she looks it.”

In addition to the traditional roster of formal dinners during the social season honoring the various branches of government, Ellen Wilson also hosted a spring season of musicales and recitals. The many southern relatives of the President and First Lady filled the guest rooms of the White House for long stays at that time also.

Ellen Wilson found escape from her social obligations by often attending the theater or the new silent “movies,” also beginning to be shown in public theaters. She further made visits to the local art galleries and museums. From the Corcoran Gallery, she had a famous canvas by artist George Watts, “Love and Life,” which pictured two nude women returned to the White House, which owned it. Edith Roosevelt had also displayed the painting in the private quarters, although Nellie Taft had sent it to the public museum. Ellen Wilson found escape from her social obligations by often attending the theater or the new silent “movies,” also beginning to be shown in public theaters. She further made visits to the local art galleries and museums. From the Corcoran Gallery, she had a famous canvas by artist George Watts, “Love and Life,” which pictured two nude women returned to the White House, which owned it. Edith Roosevelt had also displayed the painting in the private quarters, although Nellie Taft had sent it to the public museum.

Near her hometown of Rome, Georgia one Martha McChesney Berry had founded a special school to educate the children of impoverished white families who lived in the nearby mountains. As early as 1905, Ellen Wilson had been a supporter of the group, endowing a scholarship at the Berry School in honor of her late brother. She provided more direct aid and publicity to the “mountain women” of Tennessee and North Carolina in Appalachia by redecorating the blue and white presidential bedroom with furnishing fabrics and rugs hand-woven by the craftswomen, permitting it to be photographed in national publications. It helped to spur a brief but intense period of commerce for these women, who produced counterpanes, quilts, and other household furnishings. To aid fundraising efforts of the Kentucky Pine School, created to provide both traditional primary education and technical training for the poor Appalachian “Highland” children (a reference to their Scots-Irish heritage), Ellen Wilson assumed the role of honorary president for the Southern Industrial Association and in that capacity appeared at numerous public charity events in Washington.

It was also Ellen Wilson who determined to expand the third floor or “attic” of the White House, as put in place by the 1902 renovation under Theodore Roosevelt into five bedrooms. Perhaps her most enduring contribution to the presidential mansion itself, though ephemeral, was the creation of the White House Rose Garden. She travelled back to Princeton, New Jersey with her landscaper to show him some of the work she had done there and intended to copy elements of at the White House. It included a fountain and marble statue of mythic Pan, one source claiming that Ellen Wilson chose the figurine of the boy to represent the son that she had always wished for. Although Ellen Wilson’s Rose Garden did not endure through the generations to the present-day one, it was placed in the same spot, outside the West Wing and thus established the tradition. She also created a garden flanking the east colonnade, at the site of the present-day Jacqueline Kennedy Garden, installing a lily pond stocked with goldfish. It was also Ellen Wilson who determined to expand the third floor or “attic” of the White House, as put in place by the 1902 renovation under Theodore Roosevelt into five bedrooms. Perhaps her most enduring contribution to the presidential mansion itself, though ephemeral, was the creation of the White House Rose Garden. She travelled back to Princeton, New Jersey with her landscaper to show him some of the work she had done there and intended to copy elements of at the White House. It included a fountain and marble statue of mythic Pan, one source claiming that Ellen Wilson chose the figurine of the boy to represent the son that she had always wished for. Although Ellen Wilson’s Rose Garden did not endure through the generations to the present-day one, it was placed in the same spot, outside the West Wing and thus established the tradition. She also created a garden flanking the east colonnade, at the site of the present-day Jacqueline Kennedy Garden, installing a lily pond stocked with goldfish.

Ellen Wilson’s greatest legacy as First Lady was her commitment of service and support to a public welfare project intending to provide assistance to an otherwise ignored demographic. It was an effort she began eighteen days after becoming First Lady, when on 22 March 1913, she had a meeting with Charlotte Everett Wise Hopkins, the chairperson of the Women’s Committee of the National Civic Foundation’s Washington branch. A civic activist in Washington for several generations, Hopkins had first successfully engaged a First Lady in local issues when she convinced Frances Cleveland to support an annual charity Christmas party for the children of the African-American working-class in the nation’s capital city. The widespread and deplorable housing of this same demographic was the concern of Charlotte Hopkins when she convinced Ellen Wilson to join her effort to reform this problem. Ellen Wilson’s greatest legacy as First Lady was her commitment of service and support to a public welfare project intending to provide assistance to an otherwise ignored demographic. It was an effort she began eighteen days after becoming First Lady, when on 22 March 1913, she had a meeting with Charlotte Everett Wise Hopkins, the chairperson of the Women’s Committee of the National Civic Foundation’s Washington branch. A civic activist in Washington for several generations, Hopkins had first successfully engaged a First Lady in local issues when she convinced Frances Cleveland to support an annual charity Christmas party for the children of the African-American working-class in the nation’s capital city. The widespread and deplorable housing of this same demographic was the concern of Charlotte Hopkins when she convinced Ellen Wilson to join her effort to reform this problem.

Rather than simply hear about the problem that these residents who lived in crowded shacks and shanties, cramped into dirty and dark alleys in dwellings that often had no plumbing, the First Lady went to visit them herself on 25 March 1913, following a visit to a hospital for the terminally ill. Led by Hopkins, Ellen Wilson then visited four of the slum alleys, Logan Court, Neil Place, Goat Tree and Willow Tree. Shortly thereafter, she joined a social worker in a tour of newly-built model homes for low-income families, over one hundred two-family structures each of which had from two to four rooms, and were built with full utilities. These were built by the private Sanitary Housing Company; as a sign of not only her public but private commitment to the effort, the First Lady became a stockholder, investing personal funds in the endeavor. Rather than simply hear about the problem that these residents who lived in crowded shacks and shanties, cramped into dirty and dark alleys in dwellings that often had no plumbing, the First Lady went to visit them herself on 25 March 1913, following a visit to a hospital for the terminally ill. Led by Hopkins, Ellen Wilson then visited four of the slum alleys, Logan Court, Neil Place, Goat Tree and Willow Tree. Shortly thereafter, she joined a social worker in a tour of newly-built model homes for low-income families, over one hundred two-family structures each of which had from two to four rooms, and were built with full utilities. These were built by the private Sanitary Housing Company; as a sign of not only her public but private commitment to the effort, the First Lady became a stockholder, investing personal funds in the endeavor.

Although Charlotte Hopkins continued in her role as chairperson of the Women’s Committee of the National Civic Foundation’s Washington branch, Ellen Wilson assumed the title of honorary chair. There were several further tours she made to both the alley dwellings and the model homes, now with members of Congress and reform-minded political spouses accompanying her, including a young Eleanor Roosevelt, then the wife of the Assistant Navy Secretary. Civic leaders and philanthropists worked with members of the House and Senate to form a “Committee of Fifty” to begin addressing the problem with federal legislation. Ellen Wilson invited them for an initial White House meeting, where the Secretary of State pointed out that, “The fact that the wife of the President…lending support to the movement is enough” to set it off with great potential for success. Within eleven months legislation had been drafted for federal funding to clear the alley dwellings. However, a major failing of the bill was that it lacked funding for building new housing for those who would be displaced, no matter how poor the housing, the assumption being that the units that were slated for building by the private Sanitary Housing Company would suffice. Although Charlotte Hopkins continued in her role as chairperson of the Women’s Committee of the National Civic Foundation’s Washington branch, Ellen Wilson assumed the title of honorary chair. There were several further tours she made to both the alley dwellings and the model homes, now with members of Congress and reform-minded political spouses accompanying her, including a young Eleanor Roosevelt, then the wife of the Assistant Navy Secretary. Civic leaders and philanthropists worked with members of the House and Senate to form a “Committee of Fifty” to begin addressing the problem with federal legislation. Ellen Wilson invited them for an initial White House meeting, where the Secretary of State pointed out that, “The fact that the wife of the President…lending support to the movement is enough” to set it off with great potential for success. Within eleven months legislation had been drafted for federal funding to clear the alley dwellings. However, a major failing of the bill was that it lacked funding for building new housing for those who would be displaced, no matter how poor the housing, the assumption being that the units that were slated for building by the private Sanitary Housing Company would suffice.

Ellen Wilson has, however, been incorrectly credited for an effort actually initiated by her immediate predecessor Nellie Taft, with a progressive reform largely affecting African-American residents of Washington, D.C. In March of 1912, the press reported one of the first instances of a First Lady’s overt political influence, chronicling how Mrs. Taft successfully implored President Taft to issue a presidential order establishing the first health and safety regulations in the federal workplace. Nellie Taft had learned of the lack of adequate restrooms, lunchrooms, fire escapes, plumbing, electric lighting, sunlight and fresh-air windows and venting by visiting executive departmental buildings with Charlotte Hopkins of National Civic Foundation. Although the Taft Administration initiative had been ordered into effect before it ended in March of 1913, the new regulations were not put into place as the new Wilson Administration ensued.

Although she was not a federal official, Charlotte Hopkins acted as an unofficial custodian of the promised reform and wisely brought the federal government’s failure to the attention of the new First Lady. Led by Hopkins at the end of October 1913, Ellen Wilson made sudden, unannounced inspections of the Government Printing Office and the Postal Department and saw for herself what was termed “unsanitary conditions” under which lower-wage government clerks toiled, a large majority of who were women and also African-American. Despite the First Lady taking the matter up directly with Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson, he failed to take action. A visibly angered Ellen Wilson raised the problem with the President’s private adviser Edmund House at a luncheon and he finally assured her he would see to the order being carried out. Although she was not a federal official, Charlotte Hopkins acted as an unofficial custodian of the promised reform and wisely brought the federal government’s failure to the attention of the new First Lady. Led by Hopkins at the end of October 1913, Ellen Wilson made sudden, unannounced inspections of the Government Printing Office and the Postal Department and saw for herself what was termed “unsanitary conditions” under which lower-wage government clerks toiled, a large majority of who were women and also African-American. Despite the First Lady taking the matter up directly with Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson, he failed to take action. A visibly angered Ellen Wilson raised the problem with the President’s private adviser Edmund House at a luncheon and he finally assured her he would see to the order being carried out.

Why Ellen Wilson did not bring the problem directly to the President is uncertain. The dearth of information on this episode may suggest the more sensitive issue of racial segregation in the federal workplace being at the heart of the matter. President Wilson stunned and angered African American leaders who had supported his election when, instead of reducing and eradicating the separation of black and white federal employees, he upheld what was known as “Jim Crow.” This became all the more dramatically visible when the work areas of the federal buildings were reconfigured to conform to the new health and safety standards so vigorously pushed by Ellen Wilson.

Thus, some have placed blame for the Wilson Administration’s racial segregation policy on the First Lady. However, closer examination of some evidence suggests this is, at the least, partially unfair if not entirely untrue. It was in August of 1913 that the African American media and political leaders leveled angry criticism of Wilson, even personally confronting him, over the enforced segregation which was already being initiated. Ellen Wilson did not assume the crusade begun by her predecessor until two months later. Furthermore, while eviscerating the President for his policy, the leading African-American newspaper of the capital city, The Washington Bee, highly praised the First Lady for her genuine concern for the lives of those black citizens of Washington who were living and working in sub-standard conditions. There is no evidence that Ellen Wilson encouraged Jim Crow and according to later observations by her daughter Jessie, Ellen Wilson felt it her duty to help provide every opportunity for educational, employment and economic success of African-Americans. However, she maintained a traditional southerner’s view that the races should be separated in “social” arenas, although she did not include the workplace. Thus, some have placed blame for the Wilson Administration’s racial segregation policy on the First Lady. However, closer examination of some evidence suggests this is, at the least, partially unfair if not entirely untrue. It was in August of 1913 that the African American media and political leaders leveled angry criticism of Wilson, even personally confronting him, over the enforced segregation which was already being initiated. Ellen Wilson did not assume the crusade begun by her predecessor until two months later. Furthermore, while eviscerating the President for his policy, the leading African-American newspaper of the capital city, The Washington Bee, highly praised the First Lady for her genuine concern for the lives of those black citizens of Washington who were living and working in sub-standard conditions. There is no evidence that Ellen Wilson encouraged Jim Crow and according to later observations by her daughter Jessie, Ellen Wilson felt it her duty to help provide every opportunity for educational, employment and economic success of African-Americans. However, she maintained a traditional southerner’s view that the races should be separated in “social” arenas, although she did not include the workplace.

Jessie Wilson Sayre’s observations about her mother’s racial views emerged in a private interview she granted in her Cambridge, Massachusetts home on December 1, 1925, the transcript of which is now in the collections of the Library of Congress. In it, she stated explicitly: “Mrs. Wilson felt much more strongly about the color line than did Mr. Wilson. She had far more of the old southern feelings, with its curious paradox of a warm personal liking for the negroes, combined with an instinctive hostility to certain assumptions of equality.”

Ellen Wilson’s political influence on the President is believed to have been less about her raising issues with him than he seeking her opinion. According to their daughter Nell, he reviewed not only all of his important political speeches with her but “every important move.” His Treasury Secretary believed that Ellen Wilson was “the soundest and most influential” of the President’s personal advisers. Like Ida McKinley, Ellen Wilson did successfully help place several individuals who sought her intercession in their gaining federal positions of postmasters and postmistresses. She was unsuccessful in her effort to coax the President’s choice for Ambassador to Germany to accept the offer of the position. She seemed to have been a positive reinforcement behind his decision to become the first chief executive since the Federal Era to personally deliver the presidential “state of the union” report as a speech before Congress, joking that it was just the sort of innovation that former President Theodore Roosevelt would have done, “if he had thought of it.”

Capable of grasping the complexities of the currency, banking, tax, tariff and anti-trust reforms being initiated by the President, Ellen Wilson was kept closely apprised by him in letters during the summer of 1913 not only of the progress of his proposed changes to tariff rates but also the threat of conflict on the U.S.-Mexican border resulting from Mexican dictator General Victoriano Huerta, who was agitating internal strife in his country. “Perhaps it would save us trouble in the long run to give them arms and let them exterminate each other if they so prefer,” she half-jokingly suggested to him in a series of written responses. “A plague on the Monroe Doctrine! Lets throw it overboard! All the European nations have interests and citizens there as well as we, and if we could all unite in bringing pressure upon Huerta we could bring even that mad brute to hear reason.” Capable of grasping the complexities of the currency, banking, tax, tariff and anti-trust reforms being initiated by the President, Ellen Wilson was kept closely apprised by him in letters during the summer of 1913 not only of the progress of his proposed changes to tariff rates but also the threat of conflict on the U.S.-Mexican border resulting from Mexican dictator General Victoriano Huerta, who was agitating internal strife in his country. “Perhaps it would save us trouble in the long run to give them arms and let them exterminate each other if they so prefer,” she half-jokingly suggested to him in a series of written responses. “A plague on the Monroe Doctrine! Lets throw it overboard! All the European nations have interests and citizens there as well as we, and if we could all unite in bringing pressure upon Huerta we could bring even that mad brute to hear reason.”

While the President largely remained in Washington, Ellen Wilson spent her first summer as First Lady at an artist’s colony in Cornish, New Hampshire. There she devoted her time and attention to her personal ambitions as an artist, joining a circle of prominent American artists who worked in different mediums, like illustrator Maxfield Parrish, architect Charles Adams Platt and sculptor Bessie Vonnoh.

While in residence at the summer colony, Ellen Wilson joined a club of artists and when it was her turn to lead a group discussion, chose the question to be debated, “How can we best promote a fuller and more general appreciation of American art?” To the suggestion that the American federal government should use France’s model and begin to systematically promote and collect works of national importance by creating a department of the arts, the First Lady mused that “the Congressmen who would take that view….[are] not yet born.” While in residence at the summer colony, Ellen Wilson joined a club of artists and when it was her turn to lead a group discussion, chose the question to be debated, “How can we best promote a fuller and more general appreciation of American art?” To the suggestion that the American federal government should use France’s model and begin to systematically promote and collect works of national importance by creating a department of the arts, the First Lady mused that “the Congressmen who would take that view….[are] not yet born.”

A year before her husband had been elected President, Ellen Wilson submitted one of her paintings under an assumed name for consideration in a public exhibition at New York’s MacBeth Gallery on Fifth Avenue. Winning a place in the art show based on its merit alone, the gallery owner William MacBeth became her art agent and an important factor in encouraging her to begin publicly displaying her work.

Just days before her husband was elected President, Ellen Wilson’s landscape Autumn was entered in a juried show, the twenty-fifth annual Art Institute of Chicago exhibition and won a place there, before being shown at Indianapolis’s Herron Art Institute.

As she was transitioning into the White House during the late winter of 1913, Ellen Wilson’s canvases The Old Lane and Autumn Day were hung at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts annual exhibition. She joined Pen and Brush, an organization of professional women artists and writers and accepted the prestigious invitation to join what is now the National Association of Women Artists.

Perhaps the greatest professional accomplishment reached by a woman just as she was about to become First Lady was Ellen Wilson’s first one-woman art show. Fifty of her landscapes were publicly displayed in Philadelphia’s Arts and Crafts Guild, half of them selling. The New York Times reviewed her work favorably. Following her 1913 summer work in Cornish, New Hampshire, the First Lady made a private sale of four canvases, loaned one to a Cleveland art exposition and had five of her recently-completed oil landscapes were chosen for Association of Women Painters and Sculptors exhibition in New York in the autumn 1913, resulting in three being sold. Ellen Wilson donated her work income to the Berry School for mountain children. Perhaps the greatest professional accomplishment reached by a woman just as she was about to become First Lady was Ellen Wilson’s first one-woman art show. Fifty of her landscapes were publicly displayed in Philadelphia’s Arts and Crafts Guild, half of them selling. The New York Times reviewed her work favorably. Following her 1913 summer work in Cornish, New Hampshire, the First Lady made a private sale of four canvases, loaned one to a Cleveland art exposition and had five of her recently-completed oil landscapes were chosen for Association of Women Painters and Sculptors exhibition in New York in the autumn 1913, resulting in three being sold. Ellen Wilson donated her work income to the Berry School for mountain children.

Although Ellen Wilson was angered when she was allegedly quoted incorrectly by one newspaper saying,”I intend never entirely to desert my art,” she did shatter a precedent by becoming the first First Lady who managed to also simultaneously pursue her profession. There was no criticism of her doing so either in the press or public mail. Although seemingly judged on its quality, one of her submitted canvases failed to qualify for the nationally prestigious Carnegie International annual exhibit, yet when she placed in the National Academy of Design exhibition in December of 1913, some fellow artists charged that her work’s entry was based not on merit but “favoritism.”

In the White House, Ellen Wilson also created a private space for herself among the renovated rooms of the third floor, setting up her easel and paints there and establishing it as her private art studio. By the time of her return to the White House in the fall of 1913, however, she had less time to take full advantage of the space.

Woodrow Wilson was both supportive and encouraging of his wife’s professional pursuit but Ellen Wilson still made his well-being her priority. She rarely allowed herself to be separated from him and, as she had done throughout their marriage, was highly attuned to his mental and physical health, and his inclination to suffer tremendous stress from work. She encouraged of all his political accomplishments, being certain, for example, to join him in the Oval Office to witness his signing of the Federal Reserve Bill, which he considered an important accomplishment of his banking reform agenda. On the increasingly contentious issue of women’s suffrage, Ellen Wilson assumed a neutral position, welcoming activists who both supported and opposed it, although her husband refused to endorse it and her daughters favored it.

During her tenure as First Lady, Ellen Wilson assumed responsibility for planning of the 25 November 1913 East Room wedding of her daughter Jessie to Francis Sayre and also the 7 May 1914 wedding of her daughter Nell to the twenty-six years older widower and Treasury Secretary William McAdoo in the Blue Room. Although these events were of public interest, neither received the level of press coverage given to Alice Roosevelt’s 1906 White House wedding to Congressman Nicholas Longworth, a fact attributable to both Roosevelt’s comparative youth and highly visible and defined public persona.

Initially, it was believed that Ellen Wilson’s sudden loss of energy was due to her year of intense activity, culminating in the planning of the weddings and what her husband called an “ugly fall,” on 1 March 1914. It left her bruised and pained, as well as shocked. Two months later she reflected on the toll of life as a First Lady: “Nobody who has not tries can have the least idea of the exactions of life here and of the constant nervous strain of it all, - the life, combined with the constant anxiety about Woodrow, his health, the success of his legislative plans, etc. etc; If I could only sleep as he does I could stand twice as much.” It is unclear at what point she may have learned that she had a terminally-ill kidney disease known as Bright’s Disease but she kept the news from her family. Dr. Cary Grayson moved into the White House on 23 July 1914, knowing this, but it was not until 3 August 1914, that the President’s physician informed him about the true nature of his wife’s increasingly painful ailment. Two days later, the President permitted a press release to fully inform the public of her terminal condition. On her deathbed, she told the President she could “go away more cheerfully” if she knew that the alley clearance bill, still pending in Congress, would pass; word of this was sent to Capitol Hill and her request was immediately granted. Her last spoken words were to ask her physician to “promise me that you will take good care of my husband.”

Death:

6 August 1914

The White House

Burial:

Myrtle Hill Cemetery

Rome, Georgia

Ellen Wilson became the third presidential wife who died in the White House, following Letitia Tyler in 1842 and Caroline Harrison in 1892. Initially, the First Lady’s remains were rested on her White House bed. Four days after her death, a private funeral service was held for her in the East Room of the White House. Floral arrangements from around the world lined the entire east and west walls of the long room.

Her coffin was then escorted by her family on the train journey to her native Georgia, to the Rome cemetery where the late First Lady’s parents were buried.

For a full year after her burial, the grave site of the deceased First Lady remained unmarked with a headstone. Although this was not an unusual circumstance, her national status as a presidential spouse drew press attention to this fact. It was used as a point of public disapproval over the fact that her widowed husband had already begun publicly dating the woman who would become his second wife before a marker had been placed on the final resting place of his first wife. For a full year after her burial, the grave site of the deceased First Lady remained unmarked with a headstone. Although this was not an unusual circumstance, her national status as a presidential spouse drew press attention to this fact. It was used as a point of public disapproval over the fact that her widowed husband had already begun publicly dating the woman who would become his second wife before a marker had been placed on the final resting place of his first wife.

The deceased First Lady was honored by an Ellen Wilson Memorial Fund, established to create financial support for the education of impoverished children of white Appalachian families.

Although the U.S. Congress did ensure passage of an act to clear the unsanitary and unsafe slum dwellings to honor the last request of the dying First Lady, the federal funding priorities brought on with the onset of World War I essentially prevented any substantive action from taking place. In later years, a low-income housing project to provide shelter for many of the families displaced by the act was named in her honor.

MARGARET WOODROW WILSON