|

Copyright, Attention: This website and its contents contain intellectual property copyright materials and works belonging to the National First Ladies’ Library and Historic Site and to other third parties. Please do not plagiarize. If you use a direct quote from our website please cite your reference and provide a link back to the source.

First Lady Biography: Grace Coolidge

Grace Anna Goodhue Coolidge

BIRTH:

Burlington,Vermont

3 January 1879

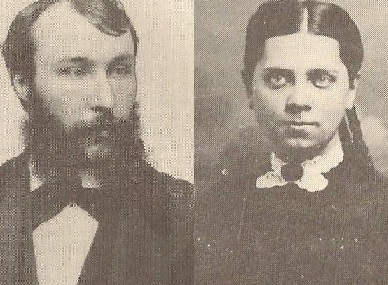

FATHER:

Captain Andrew Isaachar Goodhue (born 15 January 1848,Hancock, New Hampshire, died 25 April 1923, Burlington,Vermont). At the age of eighteen years old, Goodhue moved to Nashua, New Hampshiret o begin an apprenticeship as a mechanical engineer. Accepting a job offer as engineer of Gate’s Cotton Mill in Burlington, Vermont, he relocated there in 1870. According to his daughter’s recollections, Goodhue also performed manual labor as a mill worker. In 1886, he bought and operated a machine shop, in partnership with William Lang for two years. In 1887, as a loyal member of the Vermont Democratic Party, Goodhue was given the political appointment of Champlain Transportation Company inspector by President Grover Cleveland; this post required him to make an annual safety check of the operational functioning of commercial steamboats of the district’s waterways, including vast Lake Champlain, which included the jurisdiction of New York State. Grace Coolidge’s father taught her about the basic machinery of steamboat ships and the history of lake transportation technology. Goodhue also served as deacon of the College Street Congregational Church in Burlington. He died less than four months before his daughter became First Lady.

MOTHER:

Lemira Barrett Goodhue (born April 1848, Merrimac, New Hampshire, died 18 September 1929). Since her mother died when she was young, Lemira Barrett was raised by her maternal grandmother in Merrimac, New Hampshire and was living there when she met Andrew Goodhue in the neighboring town of Nashua. They married in Merrimac on 7 April 1870. and then moved to Burlington, Vermont. She conceived and gave birth to her only child after nine years of marriage. Her life was focused entirely on raising her daughter and on housekeeping. She strongly opposed her daughter’s budding romance with the taciturn attorney Calvin Coolidge and had advised her, to no avail, to turn down his marriage proposal. Although never overtly hostile to her son-in-law, she also never sought to befriend him. She made only one visit to the White House during her daughter’s tenure as First Lady, visiting for the March 1926 Inauguration festivities.

BIRTH ORDER AND SIBLINGS:

Only child; Grace Coolidge was the third of five First Ladies who were born as only children. The others were Eliza Johnson, Ellen Arthur, Nancy Reagan, and Laura Bush.

ANCESTRY:

English; all of Grace Coolidge’s ancestors were descended from English Puritan immigrants who arrived in the Massachusetts colony in the generation immediately following the famous first settlement at Plymouth Plantation. Her paternal ancestor William Goodhue immigrated to Lpswich, Massachusetts in 1635 and the rest of her paternal and maternal ancestors settled in the Massachusetts colony within twenty years of that date. Among her ancestors was Benjamin Goodhue, a member of the first U.S. Congress who was then elected to the U.S. Senate in 1797.

RELIGION:

Congregationalist; although born and baptized in the Methodist faith of her parents, Grace Coolidge later became a Congregationalist. Contrary to popular perception, she did not convert to this sect as a result of her marriage to Calvin Coolidge, who was also member, but rather by her own volition as a teenager. Making clear that she was never “concerned to any great extent with the differences in church creeds, nor forms of church government,” her decision to change churches was the result of an impressionable sermon. Both of her parents joined her in converting to Congregationalism.

EDUCATION:

Burlington Public School Grammar Annex, Main Street, Burlington,Vermont, 1884 –1886. Grace Coolidge attended a local public grade school in a small brick structure near her home. Eager to attend school, she was permitted to begin her education at the usually early age of five. Her teacher Cornelia C. Underwood left a memorable impression on her and they remained friends for life.

Burlington Public Middle School, Pine Street, Burlington, Vermont, 1886-1893. Grace Coolidge’s memories of her time at this grammar and middle school were of her first boyfriend and of a poor and dejected girl she befriended. During these years, she also began a private course of musical study, and her parents purchased a piano for lessons in their home.

Burlington High School, College and Willard Streets, Burlington, Vermont, 1893-1897. Grace Coolidge enrolled in what she termed the “Latin-scientific course” of study. Her instructions included Latin, two years of French language, geology, biology, and chemistry, as well as a routine course of academic study in English, math, history, geography, and literature. Grace Coolidge undertook voice lessons, trained by a public school music teacher. She also began a private course of study in elocution in which she excelled, providing her clear diction for the rest of her life and, unusually for that era, giving her a voice pattern free of regional accent. She characterized herself as both a quick learner and a procrastinator. She delivered a commencement address on “Tramp Instinct,” a topic considering the consequences of a lack of discipline and purpose in life.

University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont, 1898-1902. After graduating high school, Grace Coolidge’s uncertain health required that she remain at home before enrolling in college. The only suggestion of what might have been wrong might be discerned by the fact that, after beginning college in September of 1897, she had to drop out after two months and an “oculist” determined that she needed to spend the next several months for some type of specialized treatment in the town of Haverhill, Massachusetts, where she lived with a widowed aunt. Since the university was also in Burlington, Grace Coolidge lived at home and commuted to school. The family took in a boarder, her friend and fellow student Ivah Gale, and the two students shared a bedroom and study room in the Goodhue home. When Mrs. Coolidge was later widowed, Gale again moved in to live with her as a companion who ran the household. The Goodhue home also served as the initial meeting headquarters for the Vermont chapter of the women’s Pi Beta Phi fraternity (the term “sorority” was not yet in use) of which Grace Coolidge was a founder. She was also elected vice-president of her sophomore class. In her junior and senior years at college, Grace Coolidge also acted in minor roles of Shakespeare’s Much Ado about Nothing and Twelfth Night, performed in an open-air forum. Continuing with her music and voice lessons, she also joined the college glee club. She was nominated as one of three finalists for the college’s Julia Spear Prize for public speaking.

Clarke School for the Deaf, Northampton, Massachusetts, 1902-1904, Inspired by the example of the older June Yale, a neighbor to whom she had grown close to as a child, Grace Coolidge followed her example and avidly pursued placement in the training course for teachers at the Clarke School for the Deaf in Massachusetts, despite her mother’s wish for her to work as a teacher in Burlington, Vermont. Grace Coolidge began training in, and became an adherent of the practice of “lip-reading” for the students, as a way of mainstreaming them into the hearing world, as opposed to “sign-language.”

LIFE BEFORE MARRIAGE:

As the only child of older parents, the three-member Goodhue family was unusually close. Grace Coolidge became her mother’s constant companion, and sought to mimic her highly domestic lifestyle. As a young girl, she enthusiastically learned to knit, sew, cook, bake, clean and garden like her mother. She was notable as a child for her intelligence, and self-awareness, often found in a deep and peaceful contemplation. She also formed a close relationship with her maternal grandfather, a Union Army veteran who shared with her stories of his Civil War experiences. Although an only child, she had a large number of paternal first cousins with whom she remained close her entire life. Most of her family’s social life was centered at their Methodist Church, and Grace Coolidge spent nearly every Sunday of her youth entirely at this community center, not only at religious services and Bible study school, but also attending its lunches, dinners, and parties. As the only child of older parents, the three-member Goodhue family was unusually close. Grace Coolidge became her mother’s constant companion, and sought to mimic her highly domestic lifestyle. As a young girl, she enthusiastically learned to knit, sew, cook, bake, clean and garden like her mother. She was notable as a child for her intelligence, and self-awareness, often found in a deep and peaceful contemplation. She also formed a close relationship with her maternal grandfather, a Union Army veteran who shared with her stories of his Civil War experiences. Although an only child, she had a large number of paternal first cousins with whom she remained close her entire life. Most of her family’s social life was centered at their Methodist Church, and Grace Coolidge spent nearly every Sunday of her youth entirely at this community center, not only at religious services and Bible study school, but also attending its lunches, dinners, and parties.

As a young child, Grace Coolidge suffered from a spinal weakness and her parents put her in rigorous exercise program which strengthened the problem. Although in her advanced years, she developed upper spinal and shoulder issues, through the rest of her young and middle years she was in good health. Throughout her life, she enjoyed various sporting activities. During the long New England winters she ice-skated, tobogganed, and drove a horse sleigh.

Before she was five years old, her father was seriously injured while milling wood on the job, and his full recovery requiring his wife’s strict care, Grace Goodhue was sent for several days to live with the neighboring Yale family and she soon came to emulate the pursuit of education followed by one of the family’s daughters. When this girl later became a teacher of deaf children and brought students to her own home in Burlington, to continue their inculcation during the summer months, Grace Coolidge had her first exposure to the hearing-impaired and determined to someday do likewise.

For approximately three years, beginning with her teacher’s training course at the Clarke Institute for the Deaf (1904) and before her marriage (1905), Grace Coolidge worked as a teacher of deaf children at the school. Her initial class was of primary-school level children, followed by those at the intermediate level. Even though she ceased her active teaching once she was married, Grace Coolidge maintained a lifelong interest in the evolving training of deaf children and support of the Institute.

As a college student, Grace Goodhue dated a fellow young member of her church, Clarence Noyes. Her second boyfriend was Frank Joyner and they became close enough that, although there was no formal announcement of their wedding engagement, there was an understanding that they would eventually marry. After meeting Calvin Coolidge in 1903, during her second year of working as a teacher and their ensuing courtship, she ended her relationship with Noyes. Coolidge was a recently-established attorney and serving as Northampton’s Republican Committee chairman. Their first date was to a Republican rally at Northampton City Hall.

MARRIAGE:

26 years old, on 4 October 1905, to Calvin John Coolidge, lawyer, (born 4 July 1872, Plymouth Notch, Vermont, died 5 January 1933, Northampton, Massachusetts), at the Burlington, Vermont home of her parents at 312 Maple Street. It was a plain ceremony; Grace Coolidge wore grey, carried no flowers and guests included just a handful of relatives and close friends. After their wedding ceremony, the Coolidges took a one-week honeymoon in Montreal, Canada before settling in a rented home in Northampton.

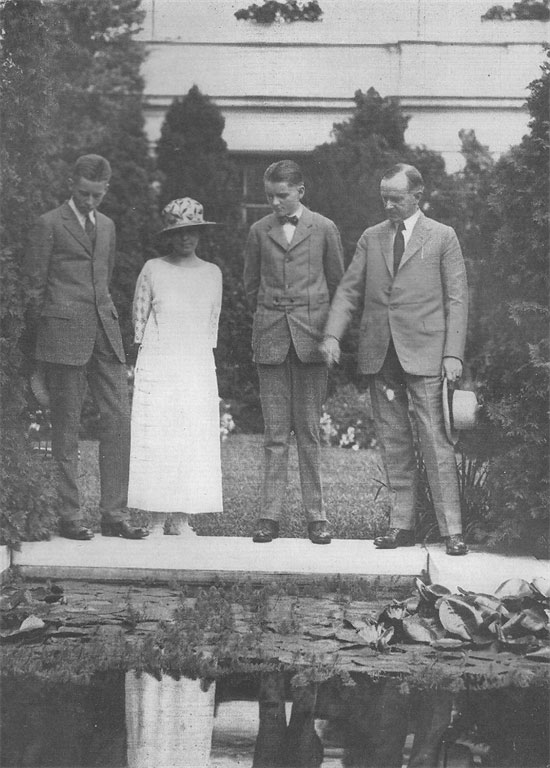

CHILDREN:

Two sons; John Coolidge (7 September 1906 – 31 May 2000), Calvin Coolidge, Jr. (13 April 1908 – 7 July 1924)

LIFE AFTER MARRIAGE:

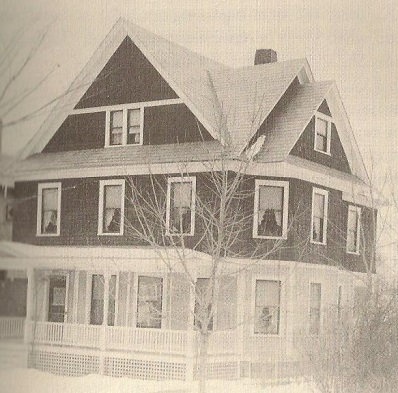

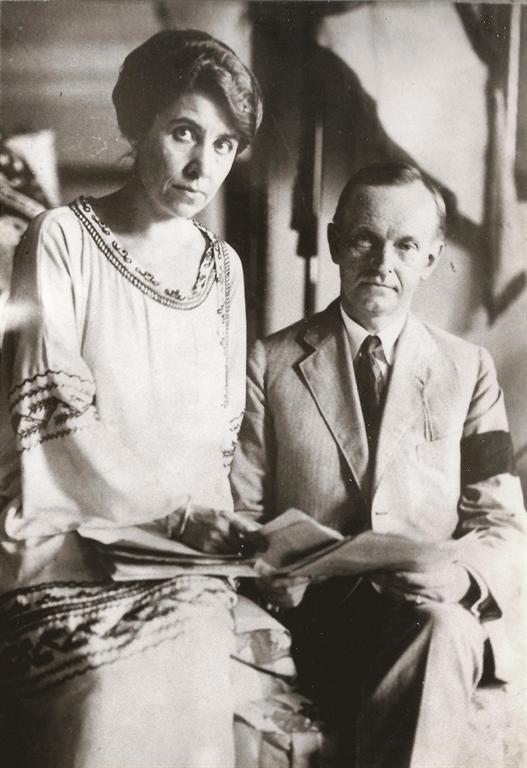

The Coolidges initially lived in a Northampton hotel that would soon go out of business and made their necessary household purchases from its linens and table service, despite being branded with the hotel monogram, using it in their home even during and after their tenure in the White House. Grace  Coolidge made reference to this fact to illustrate her essential philosophy on what she valued most about her existence, the love of family and friends. She admitted that she and her husband had “vastly different temperaments and tastes,” and that she often wrested her own inclinations in favor of those of her husband. Despite her own extroverted optimism, however, she also confessed that her effort to lighten his more dour sensibility was not “successful.” In 1906, they rented half of a two-family home which they would maintain as their residence for over twenty years, and return to after living in the White House, before purchasing their first home. Coolidge made reference to this fact to illustrate her essential philosophy on what she valued most about her existence, the love of family and friends. She admitted that she and her husband had “vastly different temperaments and tastes,” and that she often wrested her own inclinations in favor of those of her husband. Despite her own extroverted optimism, however, she also confessed that her effort to lighten his more dour sensibility was not “successful.” In 1906, they rented half of a two-family home which they would maintain as their residence for over twenty years, and return to after living in the White House, before purchasing their first home.

Following election to the state legislature, Calvin Coolidge began his term in January of 1907 and his absence from the home established a pattern for the family. Coolidge would spend the weekdays in Boston during his two consecutive one-year terms in the legislature (1907 – 1909), three consecutive one-year terms as Lieutenant-Governor (1916-1918) and one term as Governor of Massachusetts (1919-1921) [from which he was elected Vice President of the United States], while Grace Coolidge remained at home raising their sons and managing the household.

For several weeks of the summer months, when the state government was not in session and the public school term over, the family lived with Coolidge’s father at the family homestead in the rural Vermont hamlet of Plymouth Notch. There is the suggestion that, lacking the presence of her husband with whom she could consult, Grace Coolidge felt uncertain and often turned to their local minister for spiritual guidance and practical help with her sons. Perhaps as a result of her training and experience as a teacher of deaf children, Grace Coolidge was acutely sensitive to her maturing sons, both in terms of their needs and in directing their educations. She was assiduous about inculcating them with thrift and their toys and other possessions were usually hand-made or older items that were repaired. Once they were able to manage themselves, she found an increase in the social expectations of her as a political wife and chose not to return to work as a teacher of deaf children. There is the suggestion that, lacking the presence of her husband with whom she could consult, Grace Coolidge felt uncertain and often turned to their local minister for spiritual guidance and practical help with her sons. Perhaps as a result of her training and experience as a teacher of deaf children, Grace Coolidge was acutely sensitive to her maturing sons, both in terms of their needs and in directing their educations. She was assiduous about inculcating them with thrift and their toys and other possessions were usually hand-made or older items that were repaired. Once they were able to manage themselves, she found an increase in the social expectations of her as a political wife and chose not to return to work as a teacher of deaf children.

The one pre-White House period when Grace Coolidge had a public profile was during her husband’s tenure as Mayor of Northampton, Massachusetts (1910-1911) but it is difficult to discern what activities she undertook as mayoral spouse duties and which she might have done otherwise, such as her appearances at local Academy of Music events. Although they initially struggled to afford suitable clothes for their public appearances, they were eventually able to afford a maid during the first decade of their marriage, granting Grace Coolidge the freedom from ever becoming her family’s primary cook. She did, however, continue to refine her skill in knitting, finding its great value as a “stabilizer in time of perplexity or distress.”

Apart from her family duties, Grace Coolidge maintained some volunteer work with her local Church Guild. In 1912, she chaperoned a Northampton High School graduating class to Washington, D.C. and made her first visit to the White House. She also continued alumnae activity of her college sorority (“fraternity” as it was then termed), attending regional and national Pi Beta Phi conventions. She was elected president of the Western Massachusetts Alumnae Club in 1910, vice-president representing the entire eastern seaboard 1912 and president of that division three years later. As one of a circle of fifteen University of Vermont women who had founded their chapter, she attended the national association’s convention in 1915, making the trans-continental rail trip to Berkeley, California and further traveling the length of the Golden State. During World War I, she served as the co-chair of Northampton’s’ Women’s War Committee, helping to coordinate volunteer activities and food conservation drives. At that time she also began her lifelong work with the Red Cross, organizing fundraisers to benefit local men who enlisted in the armed services.

The state of Massachusetts did not provide its governor and gubernatorial family any type of state residence, so Governor Coolidge continued to live at the moderately-priced Adams House residential hotel in Boston. Her physical separation from her husband in Boston and thus removal from his official duties and ceremonial role thus permitted Grace Coolidge to live as a private citizen, despite her status as the First Lady of the state.

On rare occasion, Grace Coolidge did go to Boston in order to hear debates in the state senate and was able to witness her husband husband’s famous January 1914 speech advocating minimal government control on the lives of state residents.

Grace Coolidge was abruptly thrust from a private life to a public one during her two and half years as the Vice President’s wife (4 March 1921 – 3 August 1923). She credited Lois Marshall, the wife of her husband’s immediate predecessor, Vice President Thomas Marshall, for helping to adapt her for the sudden public expectations made of her. The initial and primary outlet for her adaptation was as “president” of an informal organization known as “The Ladies of the Senate,” a regular but informal gathering of the wives of U.S. Senators; since the Vice President presided as “president” of the Senate, his wife was invested with a parallel status among their wives and among them Grace Coolidge forged numerous bi-partisan friendships quickly. During the Vice Presidential years, her husband also came to quickly value her sociability as a political asset.

The Coolidges moved into the Willard Hotel suite which had been occupied by the previous vice-presidential couple, the Marshalls. During the months when Congress was in session, Mrs. Coolidge hosted receptions on Wednesday afternoons in the living room of their suite for any person, acquaintance or stranger, who wanted to meet her and enjoy the light refreshments she provided; these open-house events were announced to the public in newspapers. As Vice President’s wife she quickly became popular and attended more social events than she had previously. She also attended debates in the U.S. Senate and the sessions of the Washington Conference on the Limitation of Armaments in the last months of 1921 and early months of 1922.

Of the numerous political and personal associates with whom she had contact and were later to be implicated in the various collection of scandals generally labeled as “Teapot Dome,” Grace Coolidge knew nothing, nor did she indulge in speculation about any aspect of the individuals or the scandals. In later years, apologists sought to characterize her relationship as the Vice President’s wife with the incumbent President’s wife, Florence Harding, as closer than documentation indicates, though there was none of the overt hostility between them which others claimed there to be. Their interests and personalities were at great variance but Mrs. Harding’s dim view was of the Vice President and not his wife. Mrs. Harding did once express a good-natured exasperation with Mrs. Coolidge’s uncertain caution about protocol in her presence. In the days following the death and burial of President Harding, Grace Coolidge showed particular sensitivity towards the suddenly-widowed Florence Harding, assuring her that she should consider remaining in the White House for as long a period as she wished.

CAMPAIGN AND INAUGURATION:

Calvin Coolidge permitted his name to be circulated as a potential “favorite son” presidential candidate during the 1920 presidential election; when he informed his wife that he had learned that Warren G. Harding had chosen him as his vice-presidential candidate, she questioned the wisdom of his accepting the honor. It was not that she wished him to remain out of national politics but rather that he was of presidential caliber himself and assumed he would not settle for less than the highest office.

During the 1920 presidential campaign, however, Grace Coolidge made no appearances other than in their hometown of Northampton, appearing alongside her husband rather than headlining any fundraisers or events. Just prior to Election Day, she was honored at a fundraiser held by the Women’s Republican Club of Massachusetts

Not until the Harding-Coolidge ticket had won did the national press focus more intently on her. She cooperated with numerous wire service and large-circulation newspapers and also posed for numerous press photographs with her husband and sons. In December of 1920, she also traveled with her husband to Marion, Ohio to meet with the President-Elect and Mrs. Harding at their home. The two women enjoyed comparing notes on what sort of expectations would be made of them as First Lady and Second Lady and even coordinated the Inaugural ceremony outfits which they would both wear. At the 1921 Inauguration of her husband as Vice President, Grace Coolidge played no significant historical role, the event having been pared down to merely the swearing-in ceremony and Inaugural Parade. On Inauguration night, the Vice President and Mrs. Coolidge did attend a private ball hosted by Ned and Evalyn McLean, friends of the Hardings.

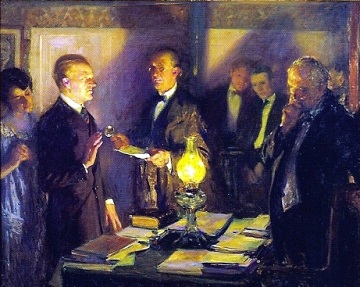

The Coolidges were at their Plymouth Notch, Vermont home when they awoken in the early morning hours of August 3, 1923 with the news that President Harding had died. Grace Coolidge lit the kerosene lamp by which her husband repeated the presidential oath of office as administered to him by his father, a notary public, and stood back to witness the historic event. She also joined the new President in returning to Washington for Harding’s funeral and to Marion, Ohio for his burial.

For much of the active period of the 1924 presidential campaign in which her husband, as the incumbent President, conducted his election campaign, he and Grace Coolidge were in mourning for their son Calvin, who died in July. Had this tragedy not occurred it is possible that Grace Coolidge might have played a more public role in the campaign.

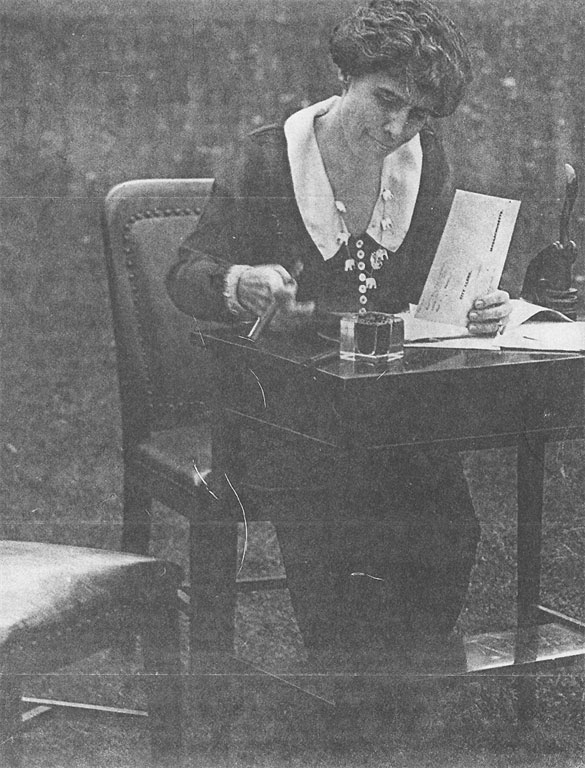

On 30 October 1924, she did participate in a small but significant politically non-partisan gesture to encourage women to exercise their right to vote for the second time since passage of the 18thAmendment. Having her personal desk brought out onto the South Lawn, she sat and filled out an absentee ballot while press photographers recorded the simple act and disseminated it through newspapers. Mrs. Coolidge also made at least one partisan appearance, attending a Maryland Republican women’s event where she was the guest of honor, but she did not make any public remarks. She also wrote an open letter to the women of America, outlining their civic responsibility to vote and urging them to do so.

There was also a minor press controversy during the campaign. In reaction to endless press stories of Grace Coolidge baking the family’s bread, muffins and pies, sewing, darning and knitting clothes, Democratic Party activist Elisabeth Marbury sarcastically quipped that such publicity seemed concocted as an appeal to voters. It provoked New York Republican Congressman Sol Bloom to defend the First Lady and attack Marbury for such cynicism. There was also a minor press controversy during the campaign. In reaction to endless press stories of Grace Coolidge baking the family’s bread, muffins and pies, sewing, darning and knitting clothes, Democratic Party activist Elisabeth Marbury sarcastically quipped that such publicity seemed concocted as an appeal to voters. It provoked New York Republican Congressman Sol Bloom to defend the First Lady and attack Marbury for such cynicism.

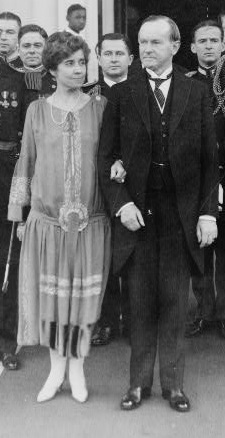

Coolidge’s 4 March 1925 Inauguration for his own full term was among a consecutive series of them, beginning with Wilson and ending with Truman which consisted merely of the swearing-in ceremony and Inaugural Parade. Mrs. Coolidge’s most prominent role during the festivities was to ride in the open car between the President and Vice President, returning from the ceremony at the Capitol to the White House where they then reviewed the parade. There was no Inaugural Ball.

FIRST LADY:

44 years old

3 August 1923 - 4 March 1929

Perception of the First Lady Role

Grace Coolidge, although not particularly a student of history, was among the earliest First Ladies to have a grasp on the evolution of her unique role within the American popular culture, especially in terms of how it limited her own activities. As she wrote with insight: “There was a sense of detachment – this was I and yet not I, this was the wife of the President of theUnited States and she took precedence over me; my personal likes and dislikes must be subordinated to the consideration of those things which were required of her.”

Grace Coolidge maintained a friendly relationship with two of her predecessors who also lived in Washington throughout her incumbency as First Lady; Helen “Nellie” Taft, whose husband, the former President, was by then the Chief Justice, and Edith Wilson, whose husband died six months after the Coolidge Administration began. She was among the first of First Ladies to pursue a study of her predecessors, writing that, “Since I went to the White House, I have read eagerly everything that I could find concerning former mistresses of the mansion and have regretted that there was so little.”

Interestingly, Calvin Coolidge appears to have been the first U.S. President to write about the role of First Lady: “The public little understands the very exacting duties that she must perform, and the restrictive life that she must lead.”

The White House and Entertaining

In the fall of 1925 marked a significant change to the small First Lady staff of one when the U.S. State Department permanently assigned a protocol expert to take charge of formal White House state dinner and other ceremonial events, liberating the Social Secretary of these duties and permitting her to focus more on direct duties aiding the First Lady. During the Lenten season, Grace Coolidge followed an informal tradition begun by Edith Roosevelt of hosting afternoon musicales of classical music. Significant artists performed during her tenure, including Sergei Rachmaninoff. In the late spring during two of her five years as First Lady she also hosted garden parties

Although there was a housekeeper, Elizabeth Jaffray, who directed the duties of the one and a half dozen members of the domestic staff, Grace Coolidge took a more pro-active oversight of overall operations; while it was a public space for ceremony and entertaining, she believed it her responsibility to run as she would her personal home. While it was widely acknowledged that she knew nothing about how the President made his choices on decisions facing him, he admitted to often being kept uninformed of her arrangements on social events.

With necessary structural renovations at the White House and an enlargement of the third floor begun in March of 1927, Grace Coolidge oversaw the temporary relocation of the presidential household to the white marble mansion of Cissy Patterson of the publishing family. It was there that they famously entertained the overnight world hero, aviator Colonel Charles Lindbergh. Upon returning to the White House with its new roof, she made frequent use of the screened-in porch atop it, calling it her “sky-parlor” and was also responsible for another innovation, on the White House grounds, a second water-lily pond landscaped near one of the two smaller gardens closer to the residence . .

She also took an unusual degree of interest in the history of the White House rooms, what had occurred there and what objects were historically associated with former residents. Hoping to provoke the public into donating items which might have once been used in the White House, Grace Coolidge successfully requested that Congress pass legislation which permitted the acceptance of any potential contributions. Disappointed at the minimal response, she was nevertheless able to refurbish the Green Room in a Colonial Revival style.

Political Role

It was ironic that Grace Coolidge would be among the earliest First Ladies to initiate federal legislation, for she was otherwise removed from the political realities of her husband’s position.

It was not for lack of interest in, or ignorance of social issues or political policy which curtailed Grace Coolidge from expressing her views in public but rather the determination of the President that it would improper for her to do so. Several factors may account for this. For example, the First Lady’s public display of interest in the Senate investigation of questionableTeapot Dome oil leases and potential bribery of Harding Interior Secretary Albert Fall by attending the hearings and following the detailed proceedings.

Grace Coolidge had no history of having previously been part of his professional work. She later mused that he might have sought to do so had she been graver by nature, but she tended to place responsibility for deficiencies in their partnership on herself, rather than him. It may simply have been the result of being physically separated from his professional life for all of their marriage until he became Vice President.

Although he did support a woman’s right to higher education and to vote, Coolidge believed that society was better served if men assumed “public” responsibility for the family by providing its financial stability while women assumed “private” responsible for its practical maintenance.

Grace Coolidge followed four predecessors who initiated federal legislation or took overtly political roles, none proving as popular as the last “non-political” First Lady Edith Roosevelt whose strict distinction between her public and private lives seems to have been successfully followed by Grace Coolidge.

Lastly, Mrs. Coolidge had a weak partisan identity, reflecting what might have been her conflicted political allegiance. She admitted that her initial political perspective had been strongly influenced by her Democratic father and then shaped by her Republican husband.

She publicly maintained that she never entered the President’s office if he was working and “knew nothing of what took place there.” She also declined to lobby the President with patronage for an individual seeking a political appointment or to foster or dissuade any federal legislation. All that she knew about the President’s policy and political decisions, she claimed, Mrs. Coolidge learned from the media, as if she were a routine member of the general public.

The President also defined other aspects of her public role as First Lady, preventing her from driving her own car, or flying in an airplane even with Colonel Charles A. Lindbergh when the aviator-hero offered to pilot her first ride in the sky, considering both activities as attracting unnecessary publicity. She also recognized the value of treating her husband in his public context, addressing him as “Mr. President” when others were in their presence.

Despite her disavowal of any political role during her husband’s presidency, Grace Coolidge nevertheless played a crucial part in it, though it was neither entirely detected by political journalists at the time nor the general public. By his own admission in remarks not published until some two decades after his death, Coolidge suffered from and intermittent but often severe social anxiety in which he was so overcome with self-consciousness that, among strangers, he simply fell into complete silence, unable or unwilling to even simply reply to small talk. In the presence of his extroverted wife, however, the President was infinitely more at ease and Grace Coolidge often carried the thread of conversation with official guests, providing him relief from the duty of initiating the sort of interaction which could facilitate subsequent, more substantive talks as part of his responsibilities.

Although this balance of the couple during their mutual social interactions with others was a dynamic which existed throughout their marriage, there is also evidence to suggest that Calvin Coolidge suffered from an untreated type of depression which Grace Coolidge invariably attempted to lighten. As she herself expressed it, “I thought I would get him to enjoy life and have fun but he was not very easy to instruct in that way.” Coolidge seemingly acknowledged this as well, writing after their silver wedding anniversary that “she has borne with my infirmities…”

One aspect of the First Lady’s personal influence on the presidency occurred in the summer of 1928 and involved the true state of his deteriorating health and her complicity in keeping it secret from the press and public. Suffering from what appeared to be severe asthma, the President’s obvious breathing problem was affecting his strength. As she wrote at the time in a private letter, he was “having a lot of trouble with his asthma, or whatever it is. This is not known outside [to the public.]” Grace Coolidge agreed to a plan to provide a plausible explanation in case the President’s physical weakness forced him to suddenly exit a public place, being that she was “not very well and had to leave.” Grace Coolidge further interceded by informing the President’s doctor that her husband had “a bad habit” of taking “various sorts of pills upon slight provocation.” There is no evidence that the President knew she had done this, or that she attempted to directly prevent what may have been a mild and naïve addiction to unknown medications.

In private, she may have also exerted some degree of influence on matters she knew were under review by him or others. There is one incident which revealed this, stemming from her admitted advocacy of the Public Buildings Act, which permitted for the review and coordination of architectural plans of federal structures, based on quality of design aesthetics. When the Commission on Battle Monuments chairman presented a draft of plans for an intended memorial to the President, the First Lady interceded during the meeting, making the case that the rectangular shaft more resembled a guillotine. Her judgment overrode that of others and the architect was ordered to draft a new design.

Personal Life as First Lady

Her affection for animals of all types was pronounced, even unusual. During the years she was Vice President’s wife, for example, she discovered a family of mice in their suite; rather than she enjoyed observing their movements and activities, even providing cracker bits for them. Rather than seeing them as unsanitary vermin she regarded the small rodents as a family unit, based on her observations, and interacted with them gently. While willing to observe the President fish, for example, she kept the fish so well-fed in the contained area where he tried to catch them that they resisted the lure of his bait. Following along on an anticipated turkey shoot on Sapelo Island, Georgia, on Christmas Day 1928, out of curiosity, she reported that none of the birds appeared and were thus killed. “Hunting never appealed to me any more than fishing,” she confessed.

Grace Coolidge enjoyed vigorous physical exercise, largely through rapid walking all over Washington, hiking arduous terrain in more remote regions of the country, and swimming. She also followed sporting events of the era, including tennis, football and baseball; not only did she attend local Washington Senators baseball games at Griffith Stadium and Army-Navy football games but she listened to games unfold via the radio. If she was unable to tune into a game on her own crystal-radio set with earphones, she often went to the White House telegraph room to keep updated on scores.

The most radical crisis imaginable to Grace Coolidge as a mother occurred in July of 1924. After playing tennis without socks, a blister on the toe of 16-year old Calvin Coolidge, Jr. and within four days developed into blood poisoning and killed him on 7 July. In the two full days of his body’s struggle to fight the infection, the First Lady remained at his bedside with genuine hope, initially at the White House and then at Walter Reed Hospital Two days before his death, the Coolidges had the crisis publicly disclosed. At the National Democratic Convention, then in session, bulletins on his condition were read to delegates and upon his death,New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered a radio message of condolence for the family.

Prayer vigils were held outside the White House for the teenager and during his East Room funeral, the Coolidges permitted the gates to be opened to the public, which was permitted to stream onto the North Lawn during the service. The First Lady received thousands of sympathy letters, particularly from parents who had experienced a similar loss. She also chose a tree growing in Vermont near his place of burial brought to the White House, where she had it planted on the lawn near the tennis courts, with a memorial plaque . The First Lady strove to maintain a sense of peace about the loss and did not fall into a deep depression as did the President, though she admitted to putting on a “stiff” front when in public, concealing her grief. Five years later, on the anniversary of his death, Grace Coolidge penned an original poem, “The Open Door,” about the depth of spirituality the loss has given her and sent it for publication to Good Housekeeping magazine. . The First Lady strove to maintain a sense of peace about the loss and did not fall into a deep depression as did the President, though she admitted to putting on a “stiff” front when in public, concealing her grief. Five years later, on the anniversary of his death, Grace Coolidge penned an original poem, “The Open Door,” about the depth of spirituality the loss has given her and sent it for publication to Good Housekeeping magazine.

Social Issues and Public Work Projects

As far as the increasing number of women who began to smoke in the 1920s, her son later said that Grace Coolidge was “liberal,” on social acceptance of this. One account claims she also tried smoking, though there is no substantial evidence of this. Although she personally questioned the wisdom of Prohibition, she herself had no interest in or history of drinking alcoholic beverages and upheld the federal restriction on serving any to her guests in public or private.

By 1924, the public ceremonies over which First Ladies was requested to preside had become routine but Grace Coolidge acquiesced to a larger number and wider variety of these; she opened annual spring flower shows, gave out Christmas toys at the local mission to children, laid building cornerstones, planted trees, and accepted May Day baskets. Continuing a tradition begun by Edith Wilson and Florence Harding, she accepted honorary presidency of the Girl Scouts and attended many of the organization’s events wearing its official uniform. By 1924, the public ceremonies over which First Ladies was requested to preside had become routine but Grace Coolidge acquiesced to a larger number and wider variety of these; she opened annual spring flower shows, gave out Christmas toys at the local mission to children, laid building cornerstones, planted trees, and accepted May Day baskets. Continuing a tradition begun by Edith Wilson and Florence Harding, she accepted honorary presidency of the Girl Scouts and attended many of the organization’s events wearing its official uniform.

Primarily, however, her public work efforts focused on two organizations: the Red Cross and Clarke School for the Deaf. Continuing Florence Harding’s commitment to the disabled World War I servicemen who lived in semi-permanence at wards established at Walter Reed Hospital, Grace Coolidge made frequent trips to read to them, brings gifts and attend the sales of wares they crafted as part of their rehabilitation therapy, doing so in the capacity of a Red Cross volunteer. She remained committed to the organization for the rest of her life.

During her tenure as First Lady, Grace Coolidge was cautious not to become a national advocate for the Clarke School and thereby assert her support of its teaching lip-reading, as opposed to those in the hearing-impaired community which favored sign language. During her tenure as First Lady, Grace Coolidge was cautious not to become a national advocate for the Clarke School and thereby assert her support of its teaching lip-reading, as opposed to those in the hearing-impaired community which favored sign language.

Nevertheless, the mere presence of the former teacher of deaf children in the White House focused national attention on a specific constituency among the larger one of those considered handicapped or challenged by a physical disability of one type or another.

Perhaps the single most powerful incident during her time as First Lady which brought public notice to fellow Americans with disabled sight or blindness was essentially a brief photo opportunity where the First Lady posed with famous deaf author Helen Keller on the South Portico steps. Perhaps the single most powerful incident during her time as First Lady which brought public notice to fellow Americans with disabled sight or blindness was essentially a brief photo opportunity where the First Lady posed with famous deaf author Helen Keller on the South Portico steps.

In the case of Keller, who was also sight-impaired, she was able to “lip-read” only by placing her hand on the First Lady’s lips, and the image was carried in newspapers and on newsreels across the country. Cautious not to exploit her continued professional interest in the work at the Clarke School,

Grace Coolidge helped to raise a $2,000,000 endowment fund for the institution during her time as First Lady, although it was the President who was largely given public credit for the achievement.

Press Coverage and Public Interaction

The level of detail about Grace Coolidge’s personal life in newspaper and magazine stories rose to one substantially higher than those of her predecessors. Her frequent public appearances in Washington and at the White House with one of her numerous animal companions, (including a raccoon briefly in the family menagerie, but more frequently one of two white collie dogs, Prudence Prim or Rob Roy), along with her relaxed and accessible nature consequently made her one of the era’s most popular figures and one mentioned with great frequency in the press.

The President determined the First Lady’s policy towards the press. When War Secretary Dwight Davis arranged to provide the First Lady with lessons in riding a horse and she made her initial visit to the stables at the military base at Fort Myer, Virginia in a pair of riding jodhpurs, the press reported the incident with flattering remarks about her physicality. First learning of it from the newspaper, the President reacted with a famous remark to her about a First Lady’s public role: “…you will get along at this job fully as well if you do not try anything new.” After his death, Grace Coolidge compared his rebuke to a “death notice” for her enthusiasm.

She strictly maintained a rule of granting no interviews or giving any public remarks or speeches. At one gathering of women reporters, she seemed to either tease them or her own press policy by finally giving a “speech” by raising her hands and forming some words in sign language. Although trained in the school of lip-reading as a form of communication for the hearing-impaired, she also evidently knew at least some rudimentary sign language.

Her immediate predecessor Florence Harding had unwittingly helped give birth to the contemporary phenomena known as the “photo op” by posing with delegations of special interest groups, civic clubs and other organizational memberships; Grace Coolidge integrated this into the First Lady role as a near-weekly routine task. The exponential increase in groups who were welcomed at the White House meant posing with them on or near the cascading steps of the broad South Portico not just for still pictures but newsreel cameras and she began to perform gestures necessary to illustrating the nature of the meeting, be it accepting certificates or buying stamps to encourage others to do so in fundraising efforts. Previously these were activities performed by a President or both he and his wife, but with Coolidge’s social anxiety it was a task he felt well-relieved of and which Grace Coolidge undertook with enthusiasm. It became the genesis of a now-long permanent aspect of the First Lady role.

Another form of public interaction which she embraced was reading and responding to a portion of her own public correspondence. She both handwrote and typed her responses, although the vast majority of public mail was answered with her dictated responses to her sole staff member, Social Secretary Mary “Polly” Randolph . .

With her having earned a college degree and worked briefly before marriage, Mrs. Coolidge was also perceived by the press and public as a role model for young women pursuing higher education. Just after Boston University named its first woman dean, it also awarded the First Lady with an honorary degree. Her White House portrait was underwritten by a national effort of her old sorority and she posed for it wearing its membership pin. She also pressed the ceremonial button which started the 1925 Women’s World Fair in Chicago.

Grace Coolidge figured in one so-called “scandal” which was, in truth, a minor incident which the press sensationalized until it had wider repercussions. During the presidential vacation in the Black Hills of South Dakota in the summer of 1927, Grace Coolidge took a hike deep into the woods with her unmarried Secret Service agent James Haley but they lost their bearings and were away for several hours longer than intended. The long delay to her scheduled lunch with the President, combined with his natural concern for her safety led him to angrily order Haley off the First Lady’s protective detail. Reporters on the scene reported this with the suggestion of some vaguely romantic nature to the genuine and warm friendship between Haley and his charge. Not until many decades later, as documented in letters now in the Coolidge Presidential Center archives, was it revealed that Grace Coolidge felt so strongly that her husband’s rash decision had unfairly reflected poorly on Haley’s professionalism that it led her to assert this to the head of the Secret Service, with no indication that the President ever knew she did this. Grace Coolidge figured in one so-called “scandal” which was, in truth, a minor incident which the press sensationalized until it had wider repercussions. During the presidential vacation in the Black Hills of South Dakota in the summer of 1927, Grace Coolidge took a hike deep into the woods with her unmarried Secret Service agent James Haley but they lost their bearings and were away for several hours longer than intended. The long delay to her scheduled lunch with the President, combined with his natural concern for her safety led him to angrily order Haley off the First Lady’s protective detail. Reporters on the scene reported this with the suggestion of some vaguely romantic nature to the genuine and warm friendship between Haley and his charge. Not until many decades later, as documented in letters now in the Coolidge Presidential Center archives, was it revealed that Grace Coolidge felt so strongly that her husband’s rash decision had unfairly reflected poorly on Haley’s professionalism that it led her to assert this to the head of the Secret Service, with no indication that the President ever knew she did this.

Popular Culture

Unlike most of her predecessors, Grace Coolidge displayed enthusiasm for keeping current with evolving technology during her tenure as First Lady. She was an avid and early user of the radio as both a form of entertainment and news. She listened to her radio each morning in the White House, working alongside her secretary. She recalled one of her most memorable moments as being one which found her listening to music being transmitted from a far distance on the radio, while watching the famous Graf Zeppelin sailing overhead. Unlike most of her predecessors, Grace Coolidge displayed enthusiasm for keeping current with evolving technology during her tenure as First Lady. She was an avid and early user of the radio as both a form of entertainment and news. She listened to her radio each morning in the White House, working alongside her secretary. She recalled one of her most memorable moments as being one which found her listening to music being transmitted from a far distance on the radio, while watching the famous Graf Zeppelin sailing overhead.

The rapid advancement of air travel especially fascinated her and although she readily accepted the invitation of Charles Lindbergh to pilot her on an air flight in his plane, President Coolidge requested that she not do so. She noted that the radio enabled her to keep track of both Lindbergh’s flight and Robert Peary’s exploration to the North Pole.

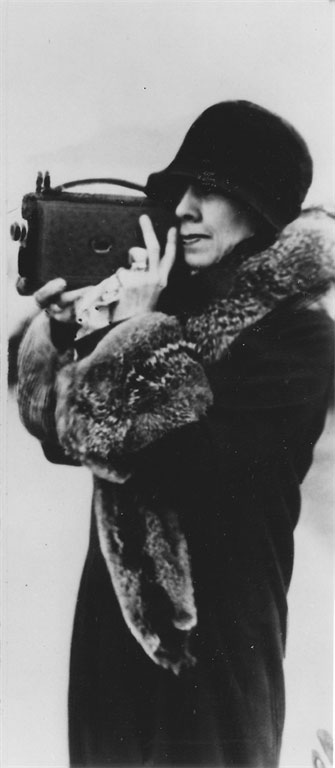

She was also current with popular literature, theater, music and movies, including Rudolph Valentino in The Sheik, which she particularly enjoyed. As entertainment for guests on the presidential yacht Mayflower, Grace Coolidge arranged for current feature films to be screened in the evenings projected on the vessel’s fantail. Her interest in film was also personal, and she purchased and operated her own hand-held “moving-picture” camera. Classical music, new music, musical theater, dance and live comedy also drew her attendance to see live performances, be if by Groucho Marx or Anna Pavlova. She was also current with popular literature, theater, music and movies, including Rudolph Valentino in The Sheik, which she particularly enjoyed. As entertainment for guests on the presidential yacht Mayflower, Grace Coolidge arranged for current feature films to be screened in the evenings projected on the vessel’s fantail. Her interest in film was also personal, and she purchased and operated her own hand-held “moving-picture” camera. Classical music, new music, musical theater, dance and live comedy also drew her attendance to see live performances, be if by Groucho Marx or Anna Pavlova.

Dressing in the looser, shorter and more revealing clothing of the Jazz Age in a modified version, she perpetuated the youthful image women of all ages were then striving to achieve. The President prevented her from wearing pants for hikes and bobbing her hair short as she wished but often bought her lavish hats and gowns for public events.  With her affinity for physical exercise she also chose a daytime wardrobe which emphasized the popular trend of women’s clothing towards sportswear. Among First Ladies Grace Coolidge has historically been cited as reflecting modern style during her tenure. She was even award a gold medal from the French government for her furthering the contemporary fashion industry. With her affinity for physical exercise she also chose a daytime wardrobe which emphasized the popular trend of women’s clothing towards sportswear. Among First Ladies Grace Coolidge has historically been cited as reflecting modern style during her tenure. She was even award a gold medal from the French government for her furthering the contemporary fashion industry.

Travel

In a move anticipating the sentiments of future Presidents to bring the presidency out of Washington and out to the rest of the country, Grace Coolidge encouraged the temporary relocation of the executive branch headquarters. In 1925, due to the failing health of the President’s father they relocated to Swampscott, Massachusetts, relatively close to his Vermont home. In 1926, it was to White Pine Camp in the Adirondack Mountains, located in a town by the name of Paul Smiths, in New York. In 1927, it was to the Black Hills of South Dakota, where they made the State Game Preserve’s Game Lodge the temporary White House. In 1928, their final summer of the presidential years, the Coolidges relocated to the island of Brule, Wisconsin.

In January of 1928, Grace Coolidge accompanied the President on a brief trip to Cuba, making her the third-known First Lady to leave the U.S. during her incumbency, the first two being Ida McKinley who briefly crossed the border for an breakfast event honoring her in Mexico (1901) and Edith Wilson, who sailed to Europe with the President in the post-World War I era.

End of Administration

There is one potential inconsistency in her purported divorce from the President’s decisions. When U.S. Senator Arthur Capper (Kansas) suggested that she had previously known about the President’s decision to not seek re-election in 1928 before he publicly announced it on 2 August 1927, Grace Coolidge reacted with surprise – not of his suggestion but of his revelation. She claimed that not until Capper mentioned it did she have any idea that the President would make such an announcement, which occurred while she was out walking in a remote wooded area with no access to the breaking news. She used this story to illustrate her claim that the President did not seek her opinion on decisions he made which, though having a public impact, more directly affected her personal life. Consistently honest, there was no reason to doubt her claim; her completion of a Lincoln Bedroom quilt into which she had sewn in the completion year of the Administration, however, occurred before his announcement. It may be that he had privately assured her he would not run but had not entirely committed to his decision when he told her this.

It is also claimed that she casually remarked to a friend that her husband “says a depression is coming” upon leaving the White House; if true, it also suggests that she kept abreast of internal political matters to a greater degree than perhaps even her husband realized.

LIFE AFTER THE WHITE HOUSE:

After leaving the White House, the Coolidges returned to live in their portion of the simple two-family home they had leased since the beginning of their marriage. After fifteen months of curious tourists driving past the house to glimpse them, they finally purchased a large, gabled home located on a seven acre plot on the Connecticut River, and protected by a gate.

Her personal popularity continued in the post-White House years. She was named as one of the nation’s “twelve greatest women” by Good Housekeeping magazine. Three months after leaving the White House, Grace Coolidge was honored by Smith College with an honorary degree; a year later, the University of Vermont awarded her one as well. She took a western trip with the former President, visiting Hollywood studios, the estate San Simeon of William Randolph Hearst, and the dedication of Arizona’s Coolidge Dam where they were joined by Will Rogers.

Inspired by the lack of first-hand accounts of her predecessors’ experiences as First Ladies, Grace Coolidge undertook a writing project to record the anecdotal stories of her life before and after marriage, concluding with the end of her tenure in March, 1929. Typing the manuscript herself, the portion of her short autobiography covering her years in Washington were published in a series of two American Magazine articles, in the fall 1929 and winter 1930 issues. Some sixty years later, the full version was posthumously published. She also successfully submitted several poems for publication in Good Housekeepingmagazine.

Among the more startling of her post-White House activities was her willingness to no longer merely appear in newsreels, but to deliver remarks that were sound-recorded. She did this on at least three occasions: an Armistice Day visit to a veterans care facility as a representative of the Red Cross; a local “Christmas Seal” stamp drive to fundraise against tuberculosis; and a Clarke School ceremony.

First Lady Grace Coolidge in her first talkie movie newsreel, 1929

Calvin Coolidge died of a heart attack on 5 January 1933. For the quarter of a century she lived as a widow, however, Grace Coolidge avoided any involvement in biographies or books assessing his presidency, not wanting to appear censorious. She placed much of their furniture up for auction to donate the proceeds to the Red Cross. In 1937, she was awarded a $5000 annual presidential widow’s pension.

She assumed her late husband’s position on the Clarke School for the Deaf board of directors and went on to serve as its president, from 1935 to 1952. She arranged for the Boston Red Sox to play at least one game in which some of the ticket price was donated to Clarke School. She resumed her focused commitment to the school, leading the effort for its development fund not just to fundraise but “educate the general public about the enormous problems which face a deaf child.” As new electronic aids were developed to help the hearing-impaired she attended demonstrations to assess the value of the latest technologies, as well as newly-developed techniques such as experimental phonetics. She also followed general electronic breakthroughs in an effort to determine if these could be harnessed in the school’s work. She further delved into related issues, such as the psychological impact of living with hearing-impairment. Among those she befriended in the 1950s was a fellow Clarke School trustee and then-U.S. Senator John F. Kennedy.

Remaining committed to a variety of civic causes, the widowed Grace Coolidge also expanded her life in new directions. In the warm weather she made regular trips to Boston as a loyal baseball fan of the Boston Red Sox, always given a place of honor and coming to know many individual players. In 1934, she wore glasses as a disguise during her sole return trip to Washington, as a tourist, and went undetected. Having learned to drive her own car, she made an extensive auto tour of Europe in 1936 with a friend and spent each spring in the friend’s North Carolina cabin. That same year she moved into her own home, “Road Forks,” which she designed, and also finally made her first airplane ride. With several strong friendships among other single women, she had no interest in a second marriage although the widowed Everett Sanders, President Coolidge’s Chief of Staff, did propose to her.

Although she had become a close personal friend of her immediate successor Lou Hoover, once Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected and went on to serve his four terms, Grace Coolidge became especially supportive of him once World War II broke out. When reporters asked if she would be voting for the 1936 Republican presidential candidate running against Rooseveltfor his second term, she declined to respond. Although she made no return visit to the White House, she did welcome First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt whenever her schedule brought her to Northampton’s Smith College. She would also initiate supportive contact by letter with successors Bess Truman and Mamie Eisenhower.

Grace Coolidge assumed several civic leadership roles of volunteer organizations during World War II, including honorary chair of the local Fight for Freedom Committee, which opposed the isolationist sentiments of many Republicans with whom she was friends. She also assumed leadership roles in efforts to provide refuge for German children and Dutch citizens victimized by Hitler’s Third Reich.

Although without title, she also became Northampton’s most visible supporter of the training school established at Smith College for women war emergency volunteers, an organization known by its acronym WAVES. She nevertheless voiced disapproval of “our justification for dropping the [atomic] bomb on a thickly populated section [Hiroshima].” In the immediate post-war era, Grace Coolidge became a particularly strong supporter of the creation of the United Nations, and even volunteered to pose for publicity photographs signing her pledge of support for the organization and its ideals.

DEATH: 8 July 1957 Northampton, Massachusetts

BURIAL: Plymouth, Vermont

|