|

Copyright, Attention: This website and its contents contain intellectual property copyright materials and works belonging to the National First Ladies’ Library and Historic Site and to other third parties. Please do not plagiarize. If you use a direct quote from our website please cite your reference and provide a link back to the source.

First Lady Biography: Elizabeth Monroe

ELIZABETH KORTRIGHT MONROE

Birth:

1768, June 30

New York City, New York

Father:

Lawrence Kortright, born 27, November 1728; a New York merchant, died in September of 1794

Mother:

Hannah Aspinwall, born 1729-1730, New York City; married 1755, May 6, at Trinity Church in New York City; died, 1777

Ancestry:

Belgian, Dutch; Elizabeth Monroe's paternal ancestry line is from Bastian Van Kortryk, a native of Belgium who immigrated to Holland about 1615. Through her mother's family, the Aspinwalls, Elizabeth Monroe was related to the Roosevelts.

Birth Order and Siblings:

Birth order not known, three sisters, one brother; Hester Kortright Gouverneur (?-?), Mary Kortright Knox (?-?), Sarah Kortright Heylinger, (?-?), John Kortright (?-1810), married Catherine Seaman in 1793

Hester Kortright married Nicholas Gouverneur in 1790 and their son married his first cousin, Maria Monroe, the daughter of James and Elizabeth Monroe. Mary Kortright married attorney Thomas Knox in 1793, a relative of the first Treasury Secretary; Sarah Kortright married John Heylinger of Sanat Cruz, a foreign diplomat.

Physical Appearance:

about five feet tall, black hair, blue eyes

Religious Affiliation:

raised in Dutch Reformed Church, married in Episcopalian service

Education:

No documentation exists. Her paternal grandmother who owned and managed her own vast real estate holdings in old Harlem, New York raised her. It was probably considered important enough to provide Elizabeth Kortright with something of a formal education; in light of her ease with life in France and Spain, she was likely instructed in French and Latin as well as the traditional " social graces " for young women of her class in literature, music, dancing and sewing.

Occupation before Marriage: Occupation before Marriage:

There is no documentation of her life previous to marriage. Considering her family's wealth and social status, as a young woman, Elizabeth Kortright Monroe was part of New York City's elite circles, but it is unlikely she was socially prominent once the American Revolution had begun, since her father was a Loyalist officer.

Marriage:

17 years old, to James Monroe, ( 28, April 1758-4, July, 1831 ) Lieutenant Colonel during American Revolution, and U.S. Congressman from Virginia, on 16 February, 1786 at Trinity Episcopal Church in New York; the couple spent a honeymoon on Long Island and then lived in the first U.S. capital city of New York with her father. Upon his retirement from Congress in 1786, they returned to his native state of Virginia where James Monroe practiced law; they lived first in Fredericksburg, and then in Charlottesville to be near his close friend, Thomas Jefferson.

Children:

Three children, two daughters, one son: Eliza Monroe Hay (1786-1840), James Spence Monroe (1799-1801) and Maria Hester Gouverneur (1803–1850)

Occupation after Marriage:

With Monroe's election to the Senate in 1790, the Monroes relocated to the new temporary capital city of Philadelphia. Elizabeth Monroe, however, spent much of her time in New York with her sisters and their families.

Four years later, when Monroe was named U.S. Minister to France, they relocated to Paris. Elizabeth Monroe was immediately fond of the city and its people, and she was well-received there by both the local and diplomatic communities. During the last days of the French Revolution, Elizabeth Monroe made a name for herself by her courageous visit to Adrienne de Noiolles de Lafayette, the imprisoned wife of the Marquis de Lafayette, who was a great personal friend of George Washington and many other revolutionary era patriots and France's most prominent supporter of American independence.

Elizabeth Monroe, in the American Embassy’s carriage, made it a point to visit the woman in prison; it was as clear a message as could be made unofficially by the U.S. government. Not wishing to offend their ally, the French government used Elizabeth Monroe’s " unofficial " interest in Adrienne de Lafayette to release her on January 22, 1795 without any official provocation and thus maintain their alliance with the U.S. yet save face for the imprisonment. Elizabeth Monroe, in the American Embassy’s carriage, made it a point to visit the woman in prison; it was as clear a message as could be made unofficially by the U.S. government. Not wishing to offend their ally, the French government used Elizabeth Monroe’s " unofficial " interest in Adrienne de Lafayette to release her on January 22, 1795 without any official provocation and thus maintain their alliance with the U.S. yet save face for the imprisonment.

Recognizing the importance placed on social behavior and appearance, Elizabeth Monroe cultivated a balanced persona that managed to embody both the casualness of American custom, while respecting old-world European protocol. She followed French ritual by refusing to make a social call on a visiting American in Paris, despite the indignant reaction it incurred. Her adoption of French clothing combined with her physical beauty earned her the appellation of “La Belle Americane.”

Further, although she was herself a Protestant, at least one prominent piece of costume jewelry she wore publicly displayed a large cross, a familiar symbol to the Catholics which composed the elite classes of France and Spain. Further, although she was herself a Protestant, at least one prominent piece of costume jewelry she wore publicly displayed a large cross, a familiar symbol to the Catholics which composed the elite classes of France and Spain.

To Europeans, unfamiliar with the social implications of “democracy,” the new form of government in the United States, Elizabeth Monroe struck a familiar tone. By her lineage, adoption of formal European aristocratic behavior and costumes which struck a modified version of those adorned by titled personages, Elizabeth Monroe put forth an image that was not unfamiliar to powerful figures on the Continent.

While never flagging in their dignified manner, it was also through the personal relationships built by the Monroes with European ministers and diplomats that foreign nations further came to accept the absolute establishment of the United States as not only a new nation, but a powerful and sophisticated one that was carrying out the principals of democracy. While never flagging in their dignified manner, it was also through the personal relationships built by the Monroes with European ministers and diplomats that foreign nations further came to accept the absolute establishment of the United States as not only a new nation, but a powerful and sophisticated one that was carrying out the principals of democracy.

The Monroes hosted American Thomas Paine in their Paris home after Monroe secured the freedom of the famous writer from prison ( he had been imprisoned for opposing the execution of King Louis XVI ). However, Paine's outrageous attacks on President Washington for letting him languish in prison for as long as he did, combined with Monroe's lavish praise of France ( in direct contradiction of Washington's strict neutrality policy ) led to his recall and the Monroe return to Virginia.

When Monroe was elected Governor of Virginia ( 1799-1803 ), Elizabeth Monroe began commuting between the capital city of Richmond and Charlottesville; during this time her father and son died and she developed serious health problems which would eventually lead to her increasing withdrawal from frequent public interaction. Many of the symptoms that were described by contemporaries suggest that it was a late-onset type of epilepsy or some illness that in later years frequently left her shaking and falling into unconsciousness. When Monroe was elected Governor of Virginia ( 1799-1803 ), Elizabeth Monroe began commuting between the capital city of Richmond and Charlottesville; during this time her father and son died and she developed serious health problems which would eventually lead to her increasing withdrawal from frequent public interaction. Many of the symptoms that were described by contemporaries suggest that it was a late-onset type of epilepsy or some illness that in later years frequently left her shaking and falling into unconsciousness.

During the Jefferson Administration, from 1803 to 1807, however, Elizabeth Monroe managed to return to Europe; the Monroes lived intermittently in London and Paris. Monroe was sent to France to help negotiate with Napoleon for the purchase of Louisiana Territory and was then named Minister to Great Britain.

London society did not highly regard the Monroes since the U.S.refused to engage itself as an ally to either France or England, and gave them the lowest possible social status; in contrast, she had an established circle of friends and acquaintances in Paris, including those rising to power in the new French government. Elizabeth and James Monroe, for example, were invited as guests to witness Napoleon’s December 2, 1804 coronation. London society did not highly regard the Monroes since the U.S.refused to engage itself as an ally to either France or England, and gave them the lowest possible social status; in contrast, she had an established circle of friends and acquaintances in Paris, including those rising to power in the new French government. Elizabeth and James Monroe, for example, were invited as guests to witness Napoleon’s December 2, 1804 coronation.

Upon returning to the U.S.and after a two-month stint as Governor of Virginia, James Monroe served as Secretary of State (1811-1817) and he and Elizabeth Monroe lived in Washington, D.C. Having purchased a private home in nearby Loudon County, Virginia, however, they spent little time in the capital; Elizabeth Monroe was rarely seen other than official functions and did not reciprocate social visits that were made to her by other spouses of officials.

Presidential Campaign and Inauguration:

Elizabeth Monroe was not known to play any role during her husband's two campaigns for the presidency in 1816 and 1820; with the winner of a presidential election still being decided by members of Congress as electors, however, the activities of which are today considered strictly social entertaining carried some potential for improving or harming the reputation of one's spouse. In this context, it can thus be concluded that despite the backlash by other political spouses and diplomats to her protocol rules that dramatically limited White House entertaining that she recovered and sustained her status and that of the President in time for his re-election.

She took a more personal if passive role during the 1817 Inauguration festivities. Since the renovations of the White House stemming from the damage the building sustained from the 1814 burning by British troops were not yet completed, the public reception following the new President's swearing-in ceremony were held in the Monroe's private home on I Street. However, Mrs. Monroe did not appear at either the swearing-in ceremony nor greet guests at the reception in her home. At the 1821 Inauguration, Elizabeth Monroe did attend the public ball, held at Brown's Hotel. She took a more personal if passive role during the 1817 Inauguration festivities. Since the renovations of the White House stemming from the damage the building sustained from the 1814 burning by British troops were not yet completed, the public reception following the new President's swearing-in ceremony were held in the Monroe's private home on I Street. However, Mrs. Monroe did not appear at either the swearing-in ceremony nor greet guests at the reception in her home. At the 1821 Inauguration, Elizabeth Monroe did attend the public ball, held at Brown's Hotel.

First Lady:

March 4, 1817 - March 4, 1825

48 years old

Despite the fact that she was First Lady for eight years, very little primary source material exists on Elizabeth Monroe. No correspondence between her and the President, her family and the general public has survived. The few documents in which her name appears relate almost exclusively to legal, financial and property matters. Despite the fact that she was First Lady for eight years, very little primary source material exists on Elizabeth Monroe. No correspondence between her and the President, her family and the general public has survived. The few documents in which her name appears relate almost exclusively to legal, financial and property matters.

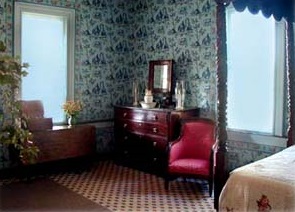

It was not Elizabeth Monroe but James Monroe who took charge of the details for the furnishings that were purchased for the newly renovated White House; thus the regal look of the mansion's new state rooms were not a reflection of any monarchial notions of Mrs. Monroe, as has sometimes been suggested. Though speculative, it is likely, however, that the First Lady had some voice in the matter and that she too preferred the emphasis on French, rather than English or American furnishings.

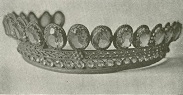

The most frequent commentary on Elizabeth Monroe related to her physical appearance. Despite her age, she looked youthful and contemporary accounts, supported by the material evidence at the Monroe Law Office and Museum in Fredericksburg, Virginia, detail the regal costumes and jewelry she wore at public occasions. With her previous life spent on the Continent, she was greatly influenced by European ways and manners. Her White House dinners were served " English style, " with one servant for each guest. In private, the Monroe family spoke only in French. The most frequent commentary on Elizabeth Monroe related to her physical appearance. Despite her age, she looked youthful and contemporary accounts, supported by the material evidence at the Monroe Law Office and Museum in Fredericksburg, Virginia, detail the regal costumes and jewelry she wore at public occasions. With her previous life spent on the Continent, she was greatly influenced by European ways and manners. Her White House dinners were served " English style, " with one servant for each guest. In private, the Monroe family spoke only in French.

Elizabeth Monroe provided an extreme contrast to her predecessor Dolley Madison, who had conceived of her role as partially a public one. As a consequence of both her fragile health and reserved social nature, as well as the prestige she hoped to convey by limiting the access of the President's wife to the spouses of other officials, Elizabeth Monroe established a European-style, less democratic protocol. Elizabeth Monroe provided an extreme contrast to her predecessor Dolley Madison, who had conceived of her role as partially a public one. As a consequence of both her fragile health and reserved social nature, as well as the prestige she hoped to convey by limiting the access of the President's wife to the spouses of other officials, Elizabeth Monroe established a European-style, less democratic protocol.

To the spouses of Judicial and Legislative branch spouses, as well as those of the foreign diplomatic corps, she would neither make nor return the formal " call, " meaning a visit that signified status and recognition from the Executive branch. President Monroe held a December 29, 1817 Cabinet meeting in which he explained the confusing rules of the new White House social policy and to also discuss how the different department heads might create their own policies in regard to social interaction with foreign dignitaries.

Elizabeth Monroe held firm and on January 22, 1818, as she began her first winter social season as First Lady, sought and gained the support of European-born and-educated Louisa Adams, the wife of the Secretary of State. Intended to increase the prestige of the Executive branch, however, it initially backfired.

When the Monroes decided to leave Washington for their nearby Virginia home instead of hosting the annual open house public reception on Independence Day in 1819, even those citizens not among the city's elite were insulted. Dissatisfaction with Elizabeth Monroe's protocol led to a boycott of all Administration receptions ( not dinners ) by officials in Washington. When Louisa Adams instituted the same social policy, her receptions were also boycotted. Finally, President Monroe held a second Cabinet meeting, on December 20, 1819. in which it was decided that while the President's family would hold steadfast to their rules, the other Executive Branch officials and their families - the Vice President and the individual Cabinet members - were free to determine their own social policy. When the Monroes decided to leave Washington for their nearby Virginia home instead of hosting the annual open house public reception on Independence Day in 1819, even those citizens not among the city's elite were insulted. Dissatisfaction with Elizabeth Monroe's protocol led to a boycott of all Administration receptions ( not dinners ) by officials in Washington. When Louisa Adams instituted the same social policy, her receptions were also boycotted. Finally, President Monroe held a second Cabinet meeting, on December 20, 1819. in which it was decided that while the President's family would hold steadfast to their rules, the other Executive Branch officials and their families - the Vice President and the individual Cabinet members - were free to determine their own social policy.

Through the second Monroe Administration, a rare time during which there was a sustained period of none of the partisanship that always marked political life in Washington, Elizabeth Monroe's policy was accepted and guests returned to the White House. It also marked her slow withdrawal from the First Lady role; one notable exception was the 1824 White House dinner honoring the touring Marquis de Lafayette, whose wife the First Lady had saved from prison in 1795.

When Elizabeth Monroe did appear at receptions and other events in which the public would see her, she appeared youthful and capable; yet she was always accompanied and protected by a circle of her female relatives. The White House did not release any information on the details of Elizabeth Monroe's health condition; had it been known that she suffered from what was then called " the falling sickness, " of epilepsy there might have been understanding. Rudimentary ignorance regarding epilepsy at the time, however, led to widespread assumptions that it was a form of mental illness, making it even more unlikely that the Monroes would not have wished to disclose the details.

Another aspect of the problem was the First Lady's reliance on her eldest daughter, Eliza Monroe Hay, married to George Hay, the former prosecutor in the trial of Aaron Burr, and a prominent Virginia attorney. Educated in the most elite Parisian school of Madame Campan, the former lady-in-waiting to Marie Antoinette, Eliza Hay frequently substituted for her mother as White House hostess and it seems evident that she established the exclusive nature of the social tone of the Administration. Eliza Hay also made much of her friendships with royalty like Hortense de Beauharnois, who became Queen of Holland and Caroline Bonaparte, who became Queen of Naples.

Contemporary accounts depict her as abrasive and snobbish; she refused to call on the diplomatic corps spouses and determined that her younger sister Maria's 9 March, 1820 White House wedding - the first of a presidential child in the mansion - would be limited to only 42 personal friends and family members and that neither official Washington nor the diplomatic corps were to acknowledge the event with presents. Contemporary accounts depict her as abrasive and snobbish; she refused to call on the diplomatic corps spouses and determined that her younger sister Maria's 9 March, 1820 White House wedding - the first of a presidential child in the mansion - would be limited to only 42 personal friends and family members and that neither official Washington nor the diplomatic corps were to acknowledge the event with presents.

To what extent Elizabeth Monroe was politically influential or expressed an opinion on the events and decisions faced by her husband are not known; it was widely accepted that after her death, James Monroe burned all their correspondence. In remembering his wife, Monroe would later write obliquely that she had shared fully in all aspects of his public service career and was always motivated by the interests of the U.S. One letter, from her influential son-in-law George Hay, however, does suggest that she was sought for her political savvy in response to at least one difficult situation involving the controversial Virginia Congressman John Randolph. She also formed enough of a close relationship with Andrew Jackson, then the popular hero of the Battle of New Orleans, to always be mentioned in the president's letters to the general. To what extent Elizabeth Monroe was politically influential or expressed an opinion on the events and decisions faced by her husband are not known; it was widely accepted that after her death, James Monroe burned all their correspondence. In remembering his wife, Monroe would later write obliquely that she had shared fully in all aspects of his public service career and was always motivated by the interests of the U.S. One letter, from her influential son-in-law George Hay, however, does suggest that she was sought for her political savvy in response to at least one difficult situation involving the controversial Virginia Congressman John Randolph. She also formed enough of a close relationship with Andrew Jackson, then the popular hero of the Battle of New Orleans, to always be mentioned in the president's letters to the general.

Post-Presidential Life:

Elizabeth Monroe was in such poor health that she and her husband had to remain in the White House three weeks after his Administration expired. Retired to their plantation estate in Loudon County, Virginia, near Washington, D.C., her activities remained centered on her family and she assumed no public role and participated in no public activities.

She traveled only to New York to visit her daughter Maria and her family, as well as her sisters and nieces and nephews. A year after leaving the White House, she suffered a seizure and collapsed near an open fireplace and sustained severe burns; she only lived three years after the accident. Upon her death, Monroe predicted that he would not live long; he died ten months later. She traveled only to New York to visit her daughter Maria and her family, as well as her sisters and nieces and nephews. A year after leaving the White House, she suffered a seizure and collapsed near an open fireplace and sustained severe burns; she only lived three years after the accident. Upon her death, Monroe predicted that he would not live long; he died ten months later.

Death:

Oak Hill estate, Loudoun County, Virginia

September 23, 1830

62 years old

Burial:

Oak Hill estate, Loudoun County, Virginia; re-interred to Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia, 1903

|