|

Copyright, Attention: This website and its contents contain intellectual property copyright materials and works belonging to the National First Ladies’ Library and Historic Site and to other third parties. Please do not plagiarize. If you use a direct quote from our website please cite your reference and provide a link back to the source.

First Lady Biography: Hannah Van Buren

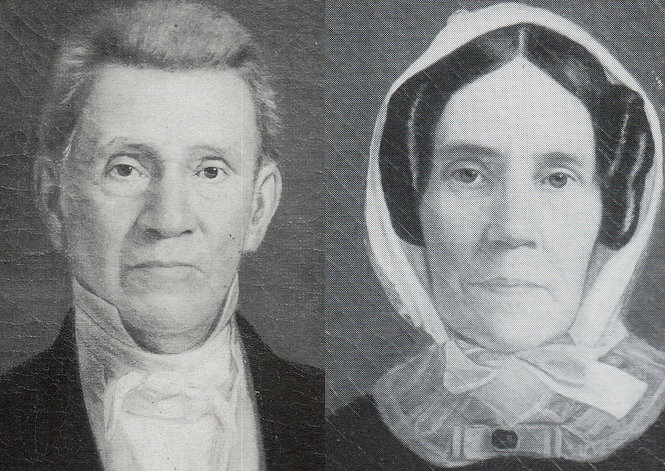

HANNAH HOES VAN BUREN

Birth:

8 March, 1783

Kinderhook, New York

Father:

Johannes Dircksen Hoes, born 25 May, 1753, Kinderhook, New York, farmer, died, 25 January, 1789

Mother:

Maria Quakenbush, born 26 January, 1754, Kinderhook, New York; married 4 February, 1776; died, 5 December, 1852

Ancestry:

Dutch; All of Hannah Van Buren's ancestors were from Holland, the last immigrating to New York state colony after 1675.

Through both paternal and maternal lines, Hannah Van Buren and Martin Van Buren were closely related, their ancestors all coming from the small Dutch community of Kinderhook. Through her mother Maria Quakenbush she was related to Elizabeth Monroe and the Roosevelts.

Birth Order and Siblings:

Birth order not known, two sisters, one brother; Maria Hoes Van Dyck (?-?), Peter I. Hoes (?-1867); Hannah Van Buren's sister Maria married the Reverend Lawrence H. Van Dyck of Stone Arabia, New York. The son of her brother John Cantine Farrell Hoes (1811-1883), was installed as pastor of the Chittenango Falls, New York Presbyterian Church, remaining until 1837, when he resigned to go to Ithaca, New York and head another church. He was a prominent member of the clergy in New York State. His only son was a chaplain in the navy.

Physical Appearance:

Blonde hair, blue eyes

Religious Affiliation:

Dutch Reformed Church, later attended and joined Presbyterian Church in Albany, New York

Education:

Hannah Van Buren was taught in a local Kinderhook school by master Vrouw Lange; Dutch was her first language

Occupation before Marriage:

No documentation of her life previous to marriage; it is highly likely that Hannah Van Buren lived as all residents of the insular community of Kinderhook did, speaking Dutch with their fellow townspeople and English with outsiders and tending to the chores of a rural life in an isolated Hudson River community. It is legend that she and Martin Van Buren were sweethearts since childhood, when he left town at age 20 to train in the law in New York City. She remained in Kinderhook. They did not marry immediately upon his return but waited until he had first established a law practice with his half-brother.

Marriage:

24 years old to Martin Van Buren (5 December 1782 - 24 July, 1862), lawyer, on 21 February 1807 at the Hoxton House Inn (owned by her brother-in-law) in Catskill, New York; the Dutch Reformed Church ceremony was performed by Judge Moses Cantine. The couple settled in Kinderhook.

Children:

Five sons, one daughter; daughter, stillborn birth, date unknown; Abraham Van Buren (27 November, 1807 - 15 March, 1873), John Van Buren (18 February, 1810 - 13, October, 1866), Martin Van Buren, Jr. (20 December, 1812 - 19 March, 1855), Winfield Scott Van Buren (born and died in 1814), Smith Thompson (16 January, 1817 - 1876)

Occupation after Marriage:

Occupation after Marriage:

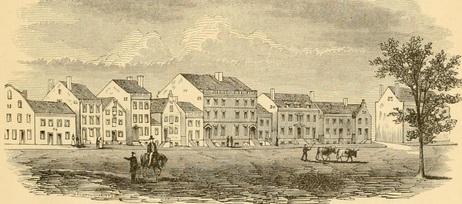

A year after their marriage, Martin and Hannah Van Buren moved from Kinderhook to the larger but nearby town of Hudson, New York, the county seat. He became immediately involved in the local Democratic Party and was named to a county position.

Following his 1812 election to the state senate, Hannah Van Buren and her family moved to Albany, New York, the state capital city. Martin Van Buren made many friends and formed a multitude of political alliances, organized his own supporters and practiced patronage in an unprecedented manner, creating one of the first "political machine" in American politics. For Hannah Van Buren this meant that her home was frequently filled with her husband's cronies and aides, lawyers and other men of influence in the state. Her own life was focused on raising four sons (she gave birth to six children within ten years), and her church.

Coming from a strong religious background, Hannah Van Buren devoted herself to the charitable efforts of the local Presbyterian Church which she joined in Albany, the new Dutch Reformed Church in that city not yet completed at the time. Little is known about her as a person, although the later New York State Democratic Party leader Benjamin Butler, who apprenticed with Van Buren in Albany and lived for a time with the family described Hannah Van Buren as “a woman of sweet nature but few intellectual gifts,” with “no love of show…no ambitious desires, no pride of ostentention.”

In Albany, Hannah Van Buren also contracted tuberculosis and rapidly developed the gaunt symptoms of that disease, which affected the ability to breathe normally. She was so weakened that she was unable to rise from her bed for more than a few minutes at a time and her young sons were able to spend only brief periods of time with her. In addition, she became pregnant for a fifth time in March of 1816.

Hannah Van Buren’s condition required the presence of her niece Christina Cantine to manage the household. Although her fifth child survived past his January 1817 birth, his delivery only further weakened Mrs. Van Buren’s condition and she was unable to recover any strength. Recognizing that she would not live long, she requested that the money usually spent in fulfilling the custom of providing scarves for the pallbearers at her funeral be abandoned and instead be used to buy food for those needy in Albany.

Even though it was claimed that her husband had said that Hannah Van Buren was the guiding force in his early life, he chose not to mention her in the nearly 800-page autobiography. Nor is there any indication that Martin Van Buren even discussed his late wife with their children once they matured. His second son John was not even certain of her correct first name; after the birth of his first daughter, he wrote his father, “We all agreed to name it after my mother. Was her name Anna or Hannah?” It may not have only been the intense grief Van Buren experienced with the loss of his wife which made him reluctant to ever discuss or even acknowledge her, but the horrific memories of how she slowly succumbed to the physical deterioration caused by tuberculosis, also caused “consumption,” because the disease seemed to literally consume the body. When, in his later years, his son Martin, Jr. also contracted tuberculosis, Martin Van Buren was frantic to save his life and took him to Europe seeking cures which offered even the slightest hope of stalling the disease. As a former President, Martin Van Buren also especially valued the presence in his home of Hannah Van Buren’s niece and nephew, Christina Cantine and Dierk Hoes.

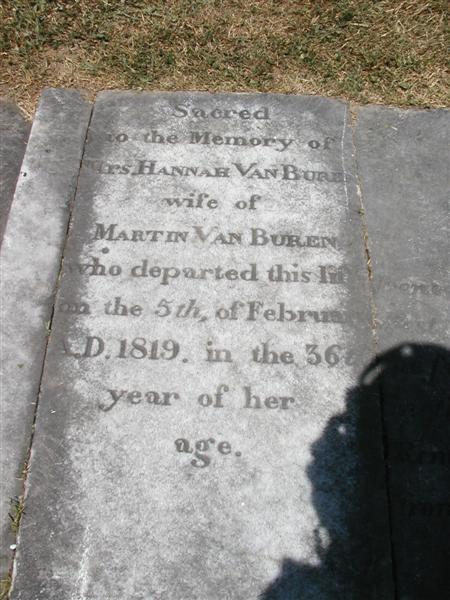

Death:

5 February, 1819

Albany, New York

Burial:

Second Presbyterian Church cemetery, Albany, New York

Re-interred at Kinderhook cemetery, Kinderhook, New York, 1855

The Van Buren Administration:

4 March, 1837- 4 March, 1841

For the first year and eight months of the Martin Van Buren presidency, there was no First Lady in the White House. Van Buren had been a widower for 18 years and he had no daughters, nor were there any women relatives of his, or spouses of Cabinet members that he either invited to preside as hostess at the White House or aid him in his own decisions regarding entertaining and decorating of the mansion's rooms.

Following the November 1838 wedding of President Van Buren’s eldest son Abraham Van Buren to Angelica Singleton, the Administration had, however belatedly, its first woman to symbolize it, in residence at the White House.

Angelica Rebecca Singleton Van Buren

Born:

13 February 1816

Wedgefield, Sumter County, South Carolina.

During at least her years at boarding school in Philadelphia, the future First Lady adopted the nickname of “Angelique,” though she signed her letters as “Angelica.”

Father:

Richard Singleton, born 5 November 1776, Sumter County, South Carolina; died 26 November 1852. Like his father and grandfather, Richard Singleton became a prosperous planter, garnering great wealth from his cultivation of cotton and peanuts. Like his father, he also took an active interest in the sport of horse racing. He developed a horse breeding business and also built a large track at his plantation “Home Place,” where he trained and raced them. Among the horses he owned were then-famous studs Crusader, Kosciusko, and Godolphin. He also managed his late father’s indigo plantation following the elder’s death. Among his business partners was one John Vaughan in Philadelphia; on business meetings in that northern city, Singleton first learned of the excellent private school Madame Grelaud’s Seminary for Young Ladies there, where he would send his daughter Mary, the only child by his first marriage. Singleton’s first wife died in 1809 after seven years of marriage. Moving among the wealthiest and most powerful circles of the Eastern Seaboard, after frequenting several mineral spring spas in mountainous Virginia, he became a substantial investor in what became the famous White Sulphur Springs resort. He died with one of his grandsons when a bridge over which the railroad train they were travelling on passed over a bridge which collapsed.

Mother:

Rebecca Travis Coles Singleton, born 2 July 1782, Albemarle County, Virginia; married Richard Singleton on 3 February 1812, Sumter County, South Carolina; died 28 May 1849, Sumter County, South Carolina). Rebecca Coles was related to many prominent political leaders. Her brother Edward Coles, after serving as President Jefferson’s private secretary, went on to become an abolitionist governor of Illinois. Her sister Sarah [Sally] was married to Speaker of the House of Representatives Andrew Stevenson, who was later appointed as U.S. Minister to Great Britain. Their first cousin was Dolley Madison.

Siblings:

Fourth of six children: Mary Singleton McDufffie (1807-1830) [half-sister]; John Coles Singleton (1813-1852); Marion Videau Singleton Deveaux Converse (1815-1867); twins Richard Singleton (1817-1833) and Matthew R. Singleton (1817-1854)

Ancestry:

English, French, and Irish: Angelica Van Buren’s great-grandfather Matthew Singleton (1730-1787) was an immigrant from the Isle of Wight in England. He settled in Virginia in 1745 but relocated seven years later to South Carolina where, by land grants, he obtained over 7,000 acres and established a plantation house called Melrose in Sumter County. Through her father’s maternal line, Angelica Van Buren was a descendant of several inter-marrying French Huguenot families who settled South Carolina. Angelica Van Buren’s mother was the granddaughter of Irish immigrant John Coles.

Religion:

Episcopalian

Education:

Columbia Female Academy, Columbia, South Carolina, 1826-1830.Richard and Rebecca Singleton believed strongly in the need to provide their daughters with an excellent and full education, beyond the traditional domestic arts. A year younger than her sister Marion, Angelica Singleton was enrolled a year behind her at Columbia Female Academy, the leading educational institution for women closest to their home in Sumter County, and founded in 1815. The principal of the school was Elias Marks, a Jewish-American and native of Charleston, South Carolina, who had dedicated his life to the higher education of women. Many of the other students were from prominent Jewish-American families and attendance at the school exposed young Angelica Singleton to many contemporaries from cultures different from her own.

Madame Greland’s Seminary for Young Ladies, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1831-1836. With no evidence of a period of a break in their educations between the two institutions they attended, Angelica and Marion Singleton were sent to this elite private boarding school for young women in Philadelphia, to continue their education.Founded in 1809 by Saint Dominguan exile Deborah Grelaud who fled her native country during the Haitian Revolution in 1793, her school provided an entirely “French-centered” education, requiring students to become fluent in French and utterly familiarized with the art, literature and culture of European nations. Enrolled from October to August, with only September off for vacation, students wore a uniform which included a plain bonnet. Rather than keep the girls apart from the cosmopolitan social scene, however, Grelaud encouraged them to attend balls lectures and the theater, browse and make purchases in the most fashionable stores and interact with men, although only from the elite class. The most musically-accomplished students also performed at private concerts for the city’s socially prominent. The exorbitant tuition limited enrollment to only the nation’s wealthiest families. Among them were several of Martha Washington’s great-granddaughters, Presidential daughter Maria Monroe, and the future First Lady of the Confederacy, Varina Davis. Angelica Van Buren also came to first socially interact with those who were Catholics and Jewish when she attended Grelaud’s.

Life Before Marriage:

Among the most revealing of documents from Angelica Van Buren’s personal library, now part of the University of South Carolina library’s collections is a bound volume that served as a yearbook for 1831 of sorts, during her time at the Grelaud Seminary. Selected by her classmates as that year’s “Queen of May” suggests she was personally popular. There is a lengthy “Address spoken by Miss A.L. Person to the Queen of May Miss Sarah Angelica Singleton, May 1 [18]31.”

The “Reply” to this was composed not by Angelica but rather her English teacher, Edward Clayson. It wittily acknowledges not only her physical beauty and the trademark curls which she would always wear, hanging alongside her cheeks down to her chin line, but also her family wealth – and how wise she was to the fact that it made her vulnerable to potential exploitation by male fortune-hunters:"Queen Angelique…Is not so weak… As some folks please to think….Men don't wed girls…For eyes or curls…But court them for their Cash."

Some of the books which she retained throughout her life were those she obtained and used while at the Grelaud Seminary, including anthologies. Some of these included biographies of the likes of Englishmen Milton, Pope, Swift, and others reflected popular British authors like Mary Shelley, Sir Walter Scott and Byron. In congregate, they suggest an early love of literature and poetry, with a preference for British works over those by Americans. The rigorous education at the Grelaud Seminary also included natural sciences and biology. Among the other books which Angelica retained was one given her in 1835 by her brother-in-law on the study of phrenology, a theoretical science which claimed that physical and mental health might be determined by the study of a person’s skull.

Angelica Van Buren’s education at the Grelaud Seminary and life in Philadelphia, however, influenced her life beyond the learning of subjects. Many families of the wealthy, Southern plantation class strongly gravitated to Philadelphia, which was becoming a base for conservative and more traditional political sensibilities, in reaction to the power of the movement to empower the working-class. The social, business and cultural interactions of elite southern families and those of Philadelphia helped forge an emerging “upper-class” American culture for the first time, which was less defined by regionalism or ancestry than by wealth and inter-marriage into other elite families. Part of this emerging “upper-class” identity was the “French-centered” education, a status symbol restricted to all but the wealthy. Those seeking to establish access to education for all classes of women charged that Grelaud seminary, and others like it were introducing an anti-democratic element into the national culture and that the emphasis on European culture diminished the new nation’s perception among its own emerging generations of wealthy and educated leaders.

Angelica Van Buren was also taught the traditional arts of music, dancing and sewing. Her letters from this period show that she developed a deeper interest in the composition, design and execution of luxurious clothing than was typical of her contemporaries. It is uncertain if she created much of her own clothing but, following the completion of her Grelaud Seminary studies, she began an active social life which would have traditionally required a large trousseau.

With her sister Marion, Angelica Singleton spent the 1836-1837 “social season,” (which ran from late November through spring) in Richmond, living with her mother’s sister [Sarah] Sally Coles Stevenson, at which time she underwent her formal social debut in that city. While there, Angelica was first introduced to the role women were increasingly beginning to play in organizing and managing public charities. Although she resented Sally Stevenson’s effort to involve her support for the aunt’s work in helping to fund and provide support for a Richmond orphanage, it was due more to the fact that she felt forced to purchase items used for the fundraising, rather than the idea of private support for institutions or the cause itself.

With Marion, Angelica Singleton spent the 1837-1838 social season in the nation's capital with another first cousin of their mother, U.S. Senator William Campbell Preston. It was another first cousin of their mother, former First Lady Dolley Madison, then living in Washington across the street from the White House, who introduced the Singleton sisters to Washington society. The high point was an invitation to accompany Mrs. Madison to a private White House dinner in March 1838 with President Martin Van Buren and the three sons then living there with him, Abraham, Martin and Smith. Marion Singleton found the President’s sons to be “pleasant, unpretentious, unpretending, civil amiable young men.” An immediate and genuine attraction developed between Abraham Van Buren and Angelica Singleton and despite knowing each other briefly, he asked her to marry him and she readily accepted.

Marriage:

22 years old, on 27 November 1838, to Abraham Van Buren (born 27 November 1807, died 15 March 1873) at the Singleton estate Home Place.

Married by the Reverend Augustus L. Converse on the groom’s 31st birthday, his father the President was unable to attend the ceremony. Abraham Van Buren, an 1827 graduate of West Point where his fellow classmates included the future Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Confederate Army commander Robert E. Lee. A career military officer, he rose in rank from second lieutenant to captain over a period of seven years. While his father was running for President in 1836, Abraham served in the Seminole Indian War.

The President reportedly approved of the marriage and the ties it brought between the White House and the powerful Southern aristocracy. As a northern Democrat, he was finding himself in an increasingly politically tenuous situation between the abolitionist sentiments of the New York machine that had supported and elected him and the rising hostility of southern Democrats who resolved to strengthen states rights as the way to ensure that slavery continued to support their agrarian economic system.

First Lady:

Days after her wedding ceremony in South Carolina, Angelica Van Buren proceeded to Washington with her husband, and moved into his suite at the White House where he worked with his brothers Martin and Smith as one of their father’s private secretaries. Settling into the presidential household just as the 1838-1839 social season began, the beginning her tenure as First Lady for more than half of the Van Buren Administration. The President’s new daughter-in-law was escorted by him into formal dinners and seated with the place of honor as the woman of highest-ranking, a status that would have been accorded a wife. She received the general public at the 1839 New Year’s Day Reception, receiving people in the oval state room (not yet decorated in blue or so designated by that color). A Boston Post reporter observing her behavior at the event noted that she was “free and vivacious in her conversation” and believed she was “universally admired” by the public crowds which met her. He assessed her as being “a lady of rare accomplishments.”

Winning praise during her initial period as First Lady in 1838-1839, Angelica Van Buren modeled her public conduct and followed the societal regulations established by Dolley Madison, evidence that she consciously sought this advice from her mother’s cousin being a rather breathless March 8, 1839 note which she sent by messenger to the former First Lady, writing “I am very anxious to see you for a few minutes top consult with you on a very important matter.”

While completing her schedule of spring 1839 public appearances as First Lady, Angelica Van Buren was also preparing for her delayed honeymoon, a lengthy tour of Europe, purchasing clothing as well as reading materials for what to anticipate. Among the books she bought was one of American author James Fenimore Cooper’s five travelogue works, written as a series of fictional letters from European countries to friends back in the states, Gleanings in Europe (1837). It is unclear if her impending trip is what inspired her purchase of the autobiography of King Henri IV’s primary advisor and a volume of the lives of French nobility in the era of Louis XIV but the books became part of her permanent library. Once in Europe, Angelica also gave especial focus to the French and English court life and customs she witnessed in London and Paris when presented to the monarchies. As many southerners began to stir with a sense of indignant outrage at the federal government’s control over what they believed were states’ rights, Angelica Van Buren may have also found particular affinity for the nationalism expressed by Scottish poet Robert Burns against the British, purchasing several volumes of his work.

At the time of Abraham and Angelica Van Buren’s trip to Europe, another son of the President, John Van Buren, was already living in London and his extravagant lifestyle and friendship with members of the nobility had led to his becoming a point of attack as “Prince John” by Van Buren’s political critics in the U.S. Since the President was a widower, by default Angelica Van Buren was perceived as the “President’s Lady” by the royal houses and although she had no technically official status, she was invited to make her formal presentation to the new British monarch Queen Victoria. Angelica Van Buren was received in a formal white satin gown which she had especially designed for her in London, and Victoria expressed an immense liking of her, though there is no record of them having further contact at that time. Giddy with her social success in London, Angelica Van Buren next went to Paris with both Abraham and John Van Buren, trailed by the press. At the court of St. Cloud, she was received as if she were American royalty by Louis Philippe.

While in London, Abraham and Angelica Van Buren lived with her aunt Sally Stevenson, who was then serving as the wife of the U.S. Ambassador to the Court of St. James. Her uncle Andrew Stevenson had been appointed Ambassador by President Jackson but engendered tremendous controversy in the British Isles after Daniel O’Connell, a political leader in Ireland, publicly denounced Stevenson as a “slave breeder,” rather than a mere “slave owner.” Insulted, Stevenson challenged O’Connell to a duel, which the Irish statesman refused to accept. It was almost certainly the fact that Stevenson was the uncle of the American First Lady which led President Van Buren not to recall the controversial Ambassador, whose continued presence in London only further deepened the British government’s criticism of the American institution of slavery. The Stevenson controversy also prompted negative association to Angelica Van Buren among those abolitionist leaders in the U.S. Whig Party which sought to defeat Van Buren’s 1840 re-election bid.

In light of the criticism she would soon receive, upon returning to the U.S. and assuming the role of White House hostess, she may not have read Gleanings in Europe closely enough to catch the subtext, Cooper warning in the volume of the inevitable pitfalls Americans would encounter when they attempted to copy European manners. Although there were apparently no critical editorials in American newspapers about Angelica Van Buren’s behavior in London and Paris, she was inspired to create a similar court life in the White House upon her return. Sally Stevenson grew alarmed by her niece’s sudden display of pretensions to nobility, reporting in a private letter that she pitied “the unfortunate being whose duty or necessity it may be to give the rousing shake…to awaken” Angelica Van Buren from “such dreams.”

After spending the summer with her family in South Carolina, Angelica Van Buren returned to live in the White House in the fall of 1839 with her husband in time to preside over the start of the 1839-1840 social season. At the 1840 New Year’s Day Reception, however, she employed a more formal manner of receiving guests from the previous year, emulating the “tableaux” technique she had seen in the British and French palaces. While neither seated on a specially-designated “throne” type of chair nor wearing a jeweled head-dress, she did pose while seated, holding a flower bouquet and set back from the public which expected the more traditionally democratic greeting of a handshake. It won her the praise of French Minister Adolphe Fourier de Bacourt, who was generally critical of Americans, he remarking that "in any country" Angelica Van Buren would "pass for an amiable woman of graceful and distinguished manners and appearance."

Her tableaux form of receiving at the 1840 New Year’s Reception, however, was almost certainly her last public appearance for the year since she was then five months pregnant and social convention dictated that pregnant women be “confined” in private. Her child, a daughter named Rebecca, was born in the White House on 27 March 1840, but only survived for five days. Little is known about Angelica Van Buren’s pregnancy except that the last trimester was concurrent with the start of the President’s bitter 1840 re-election campaign. In June, she returned to make her annual summer visit to her family in South Carolina. Although she returned to the White House that fall, she became pregnant a second time in October of 1840 and it seems unlikely that she made any but the briefest and most perfunctory public appearances during the coming social season from December 1840 to March 1841. She nevertheless figured tangentially in the campaign.

The United States was then suffering an economic depression. Angelica Van Buren's receiving style of forming a tableaux, as well as the anecdotal claim that she hoped to have the White House grounds improved to replicate those she had seen at the royal houses of Europe were fodder for a famous political attack on her father-in-law by a Pennsylvania Whig Congressman Charles Ogle. Ogle referred obliquely to Angelica Van Buren as a member of the president's household in his famous "Gold Spoon" speech. The attack was delivered in Congress and the general depiction of the President as being monarchial in his lifestyle contributed to his failure to achieve re-election during the 1840 campaign.

After the White House:

Children:one daughter, four sons; Rebecca Van Buren (1840-1840); Singleton Van Buren (1841-1879); unnamed son (1843-1843); Martin Van Buren III (1844-1889); Travis Cole Van Buren (1848-1889). None of Angelica Van Buren’s sons married, thus there are no direct descendants of Abraham and Angelica Van Buren

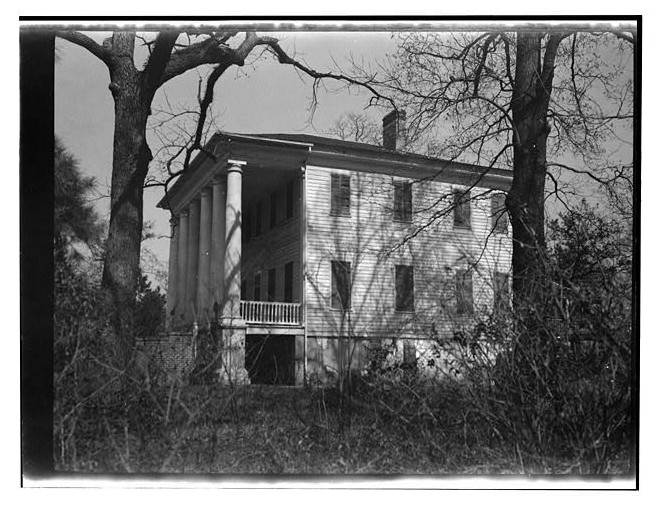

When the Van Buren Administration ended on 4 March 1841, Angelica and Abram Van Buren first proceeded to spend several months with her family in Sumter, South Carolina. There, on 22 June 1841 she gave birth to the first of three sons who lived to adulthood, Singleton. That fall the family moved into “Lindenwald,” the country estate of the former President, located in the Hudson River Valley village of Kinderhook.

Contrary to the perception of it as a retirement home, however, Lindenwald was used by Van Buren as the headquarters of his own political base with a considerably strong following, intending to again launch a run for the presidency. As the only adult woman in the family, Angelica Van Buren assumed the responsibilities of managing the largely Irish immigrant household staff and arranging the dining and overnight plans of political figures that came to confer with her father-in-law. Although Van Buren had avoided the impression of being rabidly anti-slavery, as his political philosophy evolved along with the schisms in the Democratic Party, eventually a leader of what became the Free Soil Party. Angelica Van Buren, never vociferously political, likely harbored some frustration in the household, her family’s wealth and success basely entirely on slave labor.

Angelica Van Buren’s first years at Lindenwald were enlivened by the presence of her teenage niece Mary McDuffie (born 1830). She was the daughter of Angelica’s late half-sister and the former Governor of South Carolina (1834-1842, who went on to serve as U.S. Senator (1842-1846). Although Angelica did not formally adopt the girl, Mary came to live with her in Kinderhook, becoming particularly close to the former President.

Despite his father’s opposition to the Mexican War, Abram Van Buren returned to active military duty, accepting the position of paymaster. Although he and Angelica would continue returning to Kinderhook, where they eventually maintained their own property near that of the former President, in 1848, they moved into their permanently home at 46 East 21st Street in New York City.

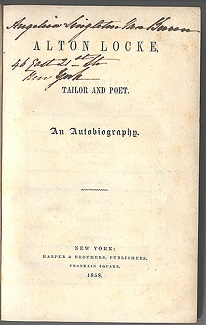

In the autumn of 1854, several months after Abraham Van Buren retired from the military, he and Angelica took their sons Travis and Martin, and her niece Mary on a tour of Europe. Including long stays in England, Scotland, France, Switzerland, Germany, Italy and Spain, it lasted well into 1856. While in England, she maintained a subscription from at least May to December of 1855, to the weekly British journal Household Words, edited by Charles Dickens. In each issue, Dickens made repeated reference to stories about those neglected members of the working-class who were suffering in poverty or with physical debility, and the moral duty of the wealthy to more justly and fully care for them. That she carried the journals with her to Switzerland and then back to the United States, rather than dispose of the pile may suggest that during this period, Angelica Van Buren became more fully aware and interested in the various types of reform movements then becoming established in Industrial Age Europe. Others of her books from this period include the memoirs of the Reverend Sydney Smith, a founder of the Edinburgh Review, who openly questioned the values of conventional religious and political institutions. Another was the 1858 novel Alton Locke, written by Charles Kingsley, a clergyman known as the “Christian Socialist.” As TK of the University of South Carolina described Kingsley’s book, it used “the form of a workingman's autobiography to address issues of religious and moral development, political reform, the effects of imprisonment, and the proper kind of poetry a moral poet should write.”

The apparent shift of focus in Angelica Van Buren’s life would seem to correlate not only with the work she soon undertook in New York City with private charities for the less fortunate but a sudden and horrifying grasp of the legal subjugation of women which arose prior to her European trip, involving her confidante and sister Marion.

Following the death of her first husband but in defiance of the objections of her own family members, Marion Singleton married Augustus L. Converse, the minister who had presided over her first wedding as well as that of Angelica. Marion initially secured a guarantee of continued ownership of her enormous property and investments rather than permitting the automatic transfer of it all to a husband as South Carolina law required. In 1853, however, she revoked this; once Converse had control of her wealth, he “went on a rampage” of spousal abuse, brutally beating Marion who then sought escape, living in a cotton field until taken in by a neighbor. A lower state court denied her plea to regain ownership of her properties. A higher state court appeal was also denied and she was granted only half of the annual income generated by her holdings. Angelica Van Buren offered Marion refuge in New York for a time. Outraged by the South Carolina court decisions, however, the former First Lady was unable to help secure justice for her sister, her network of nationally powerful political figures unable to intrude on a matter of states’ rights.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, Angelica Van Buren would likely have had to balance allegiance to the South through her birth family, and the North through her married family. The only tangential support she gave to the Confederacy was to gather donations of much-needed blankets which she sent to prisoners-of-war confined to deplorable conditions in a Union Army prison located in Elmira, New York. Yet this was also in line with her charitable efforts on behalf of prisoners in general. She seems to have been cautious in leaving little to no written record of where her genuine loyalties were during the Civil War. The South Carolina court denials of her sister Marion’s requests and her work on charities for the poor may have altered Angelica Van Buren’s view of slavery and states’ rights by this time. After the death of all of her brothers, Angelica Van Buren drew closer to her first cousin John White Stevenson, a U.S. Congressman from Virginia who, like her father-in-law supported every possible compromise effort to avert South Carolina’s secession and the ensuing war. She may have been influenced to perceive the conflict similarly, as well as by Stevenson’s protection of freed slaves during Reconstruction when he became governor of Kentucky.

Upon retiring from his military career, Abraham Van Buren worked on the editing and publication of the letters and documents from the Administration of his father, who died in 1862. Angelica’s husband died on March 15, 1873. A year later, her niece Mary died. By this time, her parents, many of her nephews and all five of her siblings had died. Although Angelica Van Buren inherited her family’s Home Place plantation in the post-Civil War era, and benefitted from what cotton and peanut production continued there, she made no further trips to South Carolina in the last years of her life.

Death:

29 December, 1878, New York City. Despite her strong identity as a South Carolinian, Mrs. Van Buren had lived more than half of her life in New York. It is unclear what caused her death at age 61 years old but she chose to be buried alongside her husband in the fashionable Woodlawn Cemetery located in the New York City borough of the Bronx, rather than the Singleton family cemetery in South Carolina.

|