|

Copyright, Attention: This website and its contents contain intellectual property copyright materials and works belonging to the National First Ladies’ Library and Historic Site and to other third parties. Please do not plagiarize. If you use a direct quote from our website please cite your reference and provide a link back to the source.

First Lady Biography: Lou Hoover

Lou Henry Hoover

Born:

29 March 1874

Waterloo, Iowa

Father:

Charles Delano Henry born 20 July 1845, Wooster, Ohio, woolen mill operator, bank clerk and partner, miner; died 21 July 1928, Palo Alto, California Charles Delano Henry born 20 July 1845, Wooster, Ohio, woolen mill operator, bank clerk and partner, miner; died 21 July 1928, Palo Alto, California

Charles Henry's grandfather, an immigrant from Ireland, helped to found the town of Wooster, Ohio. His father was superintendent of Ohio Bitumen Coal in nearby Massillon. His widowed mother relocated with him and his older brother to Iowa, where he found work as a book-keeper in a bank, thus beginning his lifelong work in various capacities in banks. Once he had helped establish a bank in Monterey, California, Henry became a partner in the bank and found the financial success that had eluded him for so long.

Mother:

Florence Ida Weed, born 1849, Wooster, Ohio; married 13 June 1873, Shell Rock, Iowa; died 24 June 1927, Palo Alto, California. As a young woman, she worked as a clerk in a dry goods store in Waterloo. Although both of Lou Hoover's parents were born in Wooster, Ohio, they both migrated, separately, with their families to Iowa, where they married. Florence Ida Weed, born 1849, Wooster, Ohio; married 13 June 1873, Shell Rock, Iowa; died 24 June 1927, Palo Alto, California. As a young woman, she worked as a clerk in a dry goods store in Waterloo. Although both of Lou Hoover's parents were born in Wooster, Ohio, they both migrated, separately, with their families to Iowa, where they married.

Siblings:

Eldest of two; one sister, Jean Henry [Large] (1882-1958)

Ancestry:

Irish, English. Lou Hoover's paternal great-grandfather William Henry was an immigrant from Ireland. Among other branches of her ancestors were those born in several of the original thirteen New England and Mid-Atlantic colonies; original immigrants and their points of known origin include: John Woolman (Aynhoe, England), Simeon Ellis (Woodale, England) and Joseph Collins (Newport, England), and William Bates (Wicklow, Ireland). She also had ancestors who fought in the American Revolution.

Religion:

Episcopalian; although she remained a member of the faith in which she was raised, she attended Quaker services with her husband, the faith in which he was raised.

Through her paternal ancestors, however, Lou Hoover did have a Quaker heritage. One of her uncles several generations back, John Woolman (1720-1772) was a prominent Quaker preacher, peace advocate and civic leader.

Appearance:

Five foot, eight inches; blue eyes; light brown hair which was white by the time she was First Lady

Education:

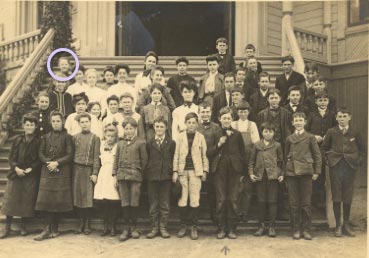

Kindergarten, Waterloo, Iowa, (1880-1881) Kindergarten, Waterloo, Iowa, (1880-1881)

Intermittent Public Grammar School, Waterloo, Iowa (1882-1887)

Los Angeles Normal School (1891-1892). An active student, she joined a school club, named after a teacher, which had members gathering small animals, rock formations and other samples of the natural world, for display in the school. She chose the school, in part, for its emphasis on physical activity even for women students and because the institution had what she said was "the best gymnasium west of the Mississippi."

San Jose Normal School (1892-1893), Lou Henry Hoover earned her teaching certificate, intending to pursue education as a profession as her mother had. San Jose Normal School (1892-1893), Lou Henry Hoover earned her teaching certificate, intending to pursue education as a profession as her mother had.

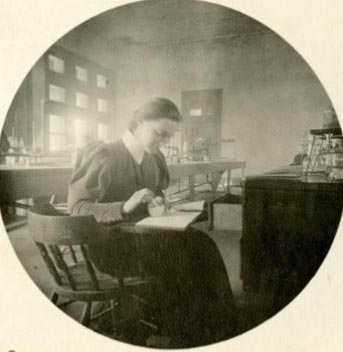

Stanford University (1894-1898), graduating with a B.A. in geology. Lou Henry was the first woman in America to have earned a degree in geology from Stanford. Her study had begun when, after attending a lecture by Stanford professor of geology J. C. Branner, she asked it he would accept a woman student. He, as well as her parents, encouraged her to pursue the field of study.

Life Before Marriage:

Although born in Waterloo, Iowa, Lou Henry Hoover lived in other states during her youth, as her father sought more lucrative employment, first at Corsicana, Texas (1879), then returning to Waterloo, and then briefly to Clearwater, Kansas (1887). The family finally settled in California, living first in Whittier (1887), then Los Angeles (1890) both in southern California, and then finally in Monterey (1892), in northern California. Although born in Waterloo, Iowa, Lou Henry Hoover lived in other states during her youth, as her father sought more lucrative employment, first at Corsicana, Texas (1879), then returning to Waterloo, and then briefly to Clearwater, Kansas (1887). The family finally settled in California, living first in Whittier (1887), then Los Angeles (1890) both in southern California, and then finally in Monterey (1892), in northern California.

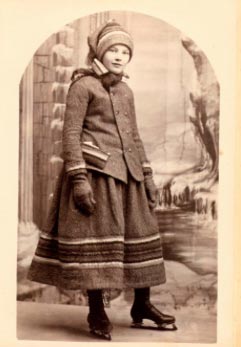

Lou Henry was consciously raised by both parents in a manner unconventional for young girls in that era. Along with being socialized to assume traditionally feminine traits, both parents encouraged her love of physical exercise and sports. Lou Henry was consciously raised by both parents in a manner unconventional for young girls in that era. Along with being socialized to assume traditionally feminine traits, both parents encouraged her love of physical exercise and sports.

She played baseball in the street, basketball, and enjoyed archery, boating, sledding, roller-skating and ice-skating. Most especially, however, she enjoyed being her father's companion in the outdoors, hiking, fishing, and camping; her lifelong love of outdoor physical exertion was borne at this time. Her father also introduced her to business issues. She was also to become an expert horsewoman, riding bareback and in the formal English style, including sidesaddle.

Despite her Midwestern roots, Lou Hoover considered herself a westerner. She took to the outdoors lifestyle of California, deepening her exploration and knowledge of the natural world. Her father continued to educate her on geological formations, plant-life, even the safety and edibility of nuts, ferns and other foods found in forests and canyons. She also learned to hunt rabbit. She also began a lifelong interest in the native culture and history of California, including a nearly-professional study of architecture. Despite her Midwestern roots, Lou Hoover considered herself a westerner. She took to the outdoors lifestyle of California, deepening her exploration and knowledge of the natural world. Her father continued to educate her on geological formations, plant-life, even the safety and edibility of nuts, ferns and other foods found in forests and canyons. She also learned to hunt rabbit. She also began a lifelong interest in the native culture and history of California, including a nearly-professional study of architecture.

As a young woman, she also showed an interest in larger public issues, as illustrated by two school essays she wrote at the age of 14: "Universal Suffrage," and "The Independent Girl."

It was during a brief period when she was working as a clerk in the bank (1893-1894) now run by her father in Monterey, that her academic pursuit of geology was prompted following a Stanford University professor's lecture on the subject. Although she was never employed as a miner or geologist, she had a professional perspective on the field as both a student and wife of a professional in the field; she later became a member of the Women's Auxiliary of the American Institute of Mining and Metallurgical Engineers. It was during a brief period when she was working as a clerk in the bank (1893-1894) now run by her father in Monterey, that her academic pursuit of geology was prompted following a Stanford University professor's lecture on the subject. Although she was never employed as a miner or geologist, she had a professional perspective on the field as both a student and wife of a professional in the field; she later became a member of the Women's Auxiliary of the American Institute of Mining and Metallurgical Engineers.

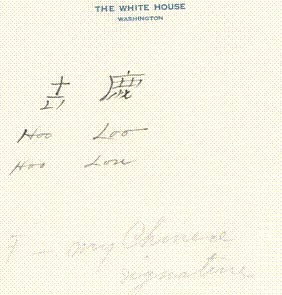

She also had a faculty with linguistics. She learned Latin at Stanford and, when going to live in China, learned Mandarin Chinese by training with a tutor. During the White House years, she was known to communicate with the President in a few words of Chinese (he did not speak it as fluently as she) when they wished to keep their conversation private. In time, she was to be fluent in five languages, including Spanish, Italian, and French. She also had a faculty with linguistics. She learned Latin at Stanford and, when going to live in China, learned Mandarin Chinese by training with a tutor. During the White House years, she was known to communicate with the President in a few words of Chinese (he did not speak it as fluently as she) when they wished to keep their conversation private. In time, she was to be fluent in five languages, including Spanish, Italian, and French.

She also had a short stint as a substitute teacher in a public schoolhouse just next to the Monterey Mission.

Marriage:

24 years old, to Herbert Clark Hoover (born 10 August 1874, West Branch, Iowa, died 26 October 1964, New York, New York) geologist, mining engineer and executive, on 10 February 1899 at the Monterey, California home of her parents.

During her first year at Stanford, her professor, J.C. Branner introduced Lou Henry to his assistant, senior class member Herbert Hoover. They not only shared an Iowa origin but a love of geology and fishing. After graduating, Hoover went to Australia as a gold miner for a British mining company. Beginning with that position, Hoover earned increasingly larger salaries, becoming a millionaire at a young age. During her first year at Stanford, her professor, J.C. Branner introduced Lou Henry to his assistant, senior class member Herbert Hoover. They not only shared an Iowa origin but a love of geology and fishing. After graduating, Hoover went to Australia as a gold miner for a British mining company. Beginning with that position, Hoover earned increasingly larger salaries, becoming a millionaire at a young age.

It was from Australian that he sent Lou Henry a telegram asking her to marry him, an offer which she accepted. With neither a Quaker nor Episcopalian minister available to perform their marriage, the Hoovers were married in a civil ceremony by Roman Catholic priest, Father Ramon Mestres, of the San Carlos Borromeo Mission. Following her graduation, in the interim, Hoover accepted the offer of the young Chinese Emperor to be Director General of the Department of Mines of the Chinese Government. Later in the day, they took the train to San Francisco. The following day, 11 February 1899, they sailed for China. It was from Australian that he sent Lou Henry a telegram asking her to marry him, an offer which she accepted. With neither a Quaker nor Episcopalian minister available to perform their marriage, the Hoovers were married in a civil ceremony by Roman Catholic priest, Father Ramon Mestres, of the San Carlos Borromeo Mission. Following her graduation, in the interim, Hoover accepted the offer of the young Chinese Emperor to be Director General of the Department of Mines of the Chinese Government. Later in the day, they took the train to San Francisco. The following day, 11 February 1899, they sailed for China.

Children:

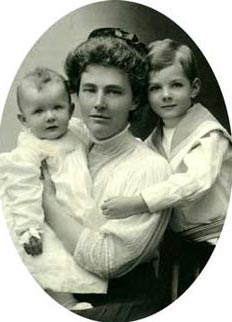

Two sons; Herbert Charles Hoover (4 August 1903 – 9 July 1969), Allan Henry Hoover (17 July 1907 – 8 November 1993) Two sons; Herbert Charles Hoover (4 August 1903 – 9 July 1969), Allan Henry Hoover (17 July 1907 – 8 November 1993)

Life Before the White House:

Lou Hoover led an extraordinarily active and public life before becoming First Lady, leading and working in many new movements and organizations, both in and outside of the United States. It might be safely stated that no previous First Lady had as wide and varied a professional life, a record perhaps matched only by her immediate successor Eleanor Roosevelt.

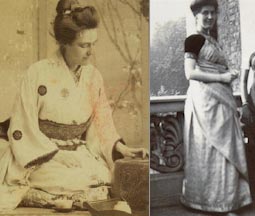

In the first weeks of her marriage, immediately following her arrival in China, Lou Hoover began an intensive study of her imminent life in the new country – the culture, the regional differences, and the history. Although based in Tientsin, she visited Peking and some interior regions. Her interest in Chinese porcelains prompted a lifelong passion for collecting samples of various period porcelains, especially of the Ming and K'ang periods. She spoke the language more easily than her husband and often translated materials for him.

One year into their residency in Tientsin, in June of 1900, the Boxer Rebellion broke out. This was a famously violent attacks and murdering by native Chinese on foreigners in a portion of the port city where they predominantly resided; the natives resented the growing internal influences of non-Chinese on their society. One year into their residency in Tientsin, in June of 1900, the Boxer Rebellion broke out. This was a famously violent attacks and murdering by native Chinese on foreigners in a portion of the port city where they predominantly resided; the natives resented the growing internal influences of non-Chinese on their society.

Throughout the crisis, Lou Hoover displayed a level-headed bravery, helping to build up protective barricades, caring for those who were wounded by gunshots, and even assuming management of a small local herd of cows to provide fresh dairy products to children. Eventually troops from the U.S., England, France and Russia arrived and patrolled the foreign-resident region along with civilians, like Lou Hoover who worked guard duty. She got around by bicycle, and learned to use a pistol as a means of self-protection. Despite her home being riddled with bullets and shells, she and her husband remained unharmed. Although she began to write a book on their experiences in China, it remained uncompleted and thus, unpublished. She did, however, publish an article on the Dowager Empress of China (1909).

In August of 1900, the Hoovers moved to London, England, Lou's husband having gone to work for the international mining outfit, Bewick, Moreing and Company. He worked for them until 1908, when he founded his own firm. Although she would move around the globe (giving birth and raising her two sons in the process), following "Bert" on assignments in European nations, India, Egypt, Australia, New Zealand, Russia, Siberia, Ceylon, Burma, and Japan, London was their base until 1914. In August of 1900, the Hoovers moved to London, England, Lou's husband having gone to work for the international mining outfit, Bewick, Moreing and Company. He worked for them until 1908, when he founded his own firm. Although she would move around the globe (giving birth and raising her two sons in the process), following "Bert" on assignments in European nations, India, Egypt, Australia, New Zealand, Russia, Siberia, Ceylon, Burma, and Japan, London was their base until 1914.

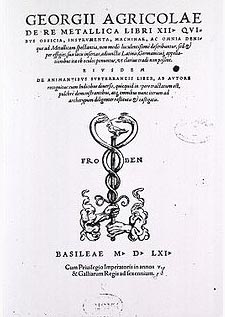

For five years during this period she began a collaborative writing project with her husband, the translation from Latin to English of a 1565 guide to mining and metallurgy, called De Re Metallica by the German mineralogist George Agricola. Published in 1912, the still-relevant work earned the couple the Mining & Metallurgical Society of America's gold medal. For five years during this period she began a collaborative writing project with her husband, the translation from Latin to English of a 1565 guide to mining and metallurgy, called De Re Metallica by the German mineralogist George Agricola. Published in 1912, the still-relevant work earned the couple the Mining & Metallurgical Society of America's gold medal.

After occupancy in a Hyde Park apartment, they bought an expansive house they called "Red House," and it became a central gathering place for many Americans and other foreigners based in London, thus widening the couples' circle into the arts, entertainment, sciences, politics, law, banking and business. A love of theater was also borne in her during this time. During this time, she published her article, "John Milne, Seismologist" (19l2).

When the conflict that would become World War I broke out in Europe in 1914, Lou Hoover helped to create and chair the American Women's War Relief Fund and Hospital, an organization to help raise immediate funds and support for the suffering. She also became a leader in the Society of American Women in London, helping to find housing, food, some financial aid and serving as an informational clearing-house to those unable to get home. With hundreds of thousands of Europeans displaced and, in the case of Belgians, whose country was occupied by Germany, widespread starvation, Hoover was asked by the American Ambassador to organize a mobilization of immediate aid from neutral countries, heading up the Commission for Relief in Belgium. When the conflict that would become World War I broke out in Europe in 1914, Lou Hoover helped to create and chair the American Women's War Relief Fund and Hospital, an organization to help raise immediate funds and support for the suffering. She also became a leader in the Society of American Women in London, helping to find housing, food, some financial aid and serving as an informational clearing-house to those unable to get home. With hundreds of thousands of Europeans displaced and, in the case of Belgians, whose country was occupied by Germany, widespread starvation, Hoover was asked by the American Ambassador to organize a mobilization of immediate aid from neutral countries, heading up the Commission for Relief in Belgium.

Bringing her own two sons back to California, Lou Hoover managed to work in partnership with him, as a special representative of the commission, organizing a special branch focused on her fellow Californians, raising money and facilitating transportation of the first boatload of food to those in need. She further encouraged the widespread sale in America of Belgian lace as a wartime means of supporting one of that nation's primary industries during the war years. Bringing her own two sons back to California, Lou Hoover managed to work in partnership with him, as a special representative of the commission, organizing a special branch focused on her fellow Californians, raising money and facilitating transportation of the first boatload of food to those in need. She further encouraged the widespread sale in America of Belgian lace as a wartime means of supporting one of that nation's primary industries during the war years.

Her article "Belgium's Needs" (1915) was also widely reprinted. Travelling between the U.S. and London, she concurrently became an organizer of the American Red Cross' Canteen Escort Service, which arranged the trans-Atlantic transportation home of wounded servicemen, create a hospital center and established a fleet of ambulances. King Albert I of Belgium would decorate her in appreciation for her substantive work, in 1919. She forever maintained an interest in the culture and people of Belgium. Her article "Belgium's Needs" (1915) was also widely reprinted. Travelling between the U.S. and London, she concurrently became an organizer of the American Red Cross' Canteen Escort Service, which arranged the trans-Atlantic transportation home of wounded servicemen, create a hospital center and established a fleet of ambulances. King Albert I of Belgium would decorate her in appreciation for her substantive work, in 1919. She forever maintained an interest in the culture and people of Belgium.

In 1917, when America entered the war, Hoover's work led to his appointment by President Woodrow Wilson as chief of the U.S. Food Administration. This brought the Hoovers to live in Washington. In 1917, when America entered the war, Hoover's work led to his appointment by President Woodrow Wilson as chief of the U.S. Food Administration. This brought the Hoovers to live in Washington.

There, as volunteer head of the Administration's Women's Committee, Lou Hoover assumed her first major high-profile role in the United States, seeking to illustrate through example, speeches and widespread media publicity how Americans – mostly women who were the primary housekeepers and consumers – could practically conserve food that was needed for American forces and ongoing refugee relief efforts.

The encouraging of Americans to go one day a week without wheat, and another day a week without meat, and using as little sugar as possible, came to be known as "Hoovering," and Lou Hoover offered recipes that adhered to these guidelines and urged citizens to plant, grow, cultivate and harvest their own produce. She even led lessons on how to do it all. The encouraging of Americans to go one day a week without wheat, and another day a week without meat, and using as little sugar as possible, came to be known as "Hoovering," and Lou Hoover offered recipes that adhered to these guidelines and urged citizens to plant, grow, cultivate and harvest their own produce. She even led lessons on how to do it all.

Lou Hoover also took a direct role in finding housing and creating a social gathering center for the thousands of single women who poured into Washington to work in government for the war effort. Her husband's work led to his being named Director General of Post War Relief and Rehabilitation.

During World War I, and in the years from 1921 to 1928, when her husband served as Commerce Secretary to President Warren Harding and his successor Calvin Coolidge, Lou Hoover came to know well three successive First Ladies, Edith Wilson, Florence Harding and Grace Coolidge. It was Lou Hoover who prevailed upon Edith Wilson to accept the role of honorary president of a new organization that she helped forge – the Girl Scouts of America. Every succeeding First Lady since Mrs. Hoover has that role. During World War I, and in the years from 1921 to 1928, when her husband served as Commerce Secretary to President Warren Harding and his successor Calvin Coolidge, Lou Hoover came to know well three successive First Ladies, Edith Wilson, Florence Harding and Grace Coolidge. It was Lou Hoover who prevailed upon Edith Wilson to accept the role of honorary president of a new organization that she helped forge – the Girl Scouts of America. Every succeeding First Lady since Mrs. Hoover has that role.

Married to an Englishman, the found of the Girl Scouts was Juliette Gordon Low. Her exposure to Great Britain's Boy Scouts and Girl Guides was the impetus to her creation of a similar healthy youth movement for young women. On 12 March 1912, she formed an American Girl Guides group with eighteen girls; a year later she changed the name to Girl Scouts. Intending to not only provide them with exposure to and respect for the natural world, but also self-reliance, discipline and resourceful thinking, she also insisted that any young women be admitted, regardless of physical disability, socio-economic, racial, religious, regional or ethnic background. Married to an Englishman, the found of the Girl Scouts was Juliette Gordon Low. Her exposure to Great Britain's Boy Scouts and Girl Guides was the impetus to her creation of a similar healthy youth movement for young women. On 12 March 1912, she formed an American Girl Guides group with eighteen girls; a year later she changed the name to Girl Scouts. Intending to not only provide them with exposure to and respect for the natural world, but also self-reliance, discipline and resourceful thinking, she also insisted that any young women be admitted, regardless of physical disability, socio-economic, racial, religious, regional or ethnic background.

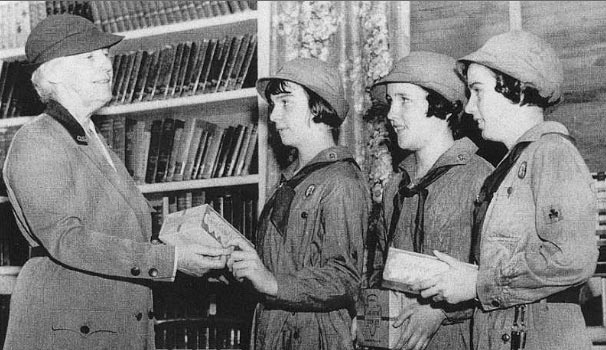

Just five years after creating the Girl Scouts, Low met Lou Hoover and, struck by the Californian's own grounding in a childhood spent camping, hiking and exploring the natural world, immediately recruited her into the organization's leadership. Lou Hoover began her work with the organization as a National Commissioner (1917-1918). One aspect of the movement that especially appealed to Lou Hoover was the potential for mobilizing thousands of healthy young women to respond to crises and disaster, an effort with which she had practical experience during World War I.

One such effort she found viable was teaching the growing membership how to prepare, cultivate, harvest and re-soil vegetable war gardens. She was not above taking a hoe and illustrating the process herself. Further, she saw a strong connection between mental and emotional clarity and spending time in physical exertion in the natural, outdoor setting. At its most basic level, she believed the benefit to the mind and the body from scouting activities would manifest in the lives of maturing girls in both traditional roles as homemaker, wife and mother, but also in the community as activists and participants in civic-related projects.

Despite her status and the spousal obligations that continued for her as a Cabinet wife, Lou Hoover played a substantive and important role at the national level in the founding years of the Girl Scouts. During the Harding and Coolidge Administrations, Lou Hoover was first Vice President (1921), then promoted to President of the organization (1922-1925), then returned to being Vice President (1925-1929). She also served as Chairman of the Girl Scouts National Board of Directors for part of this time (1925-1928). She even assisted her sister Jean Large, a professional writer, in drafting Nancy Goes Scouting, a book for young adults in the late 1920's. Despite her status and the spousal obligations that continued for her as a Cabinet wife, Lou Hoover played a substantive and important role at the national level in the founding years of the Girl Scouts. During the Harding and Coolidge Administrations, Lou Hoover was first Vice President (1921), then promoted to President of the organization (1922-1925), then returned to being Vice President (1925-1929). She also served as Chairman of the Girl Scouts National Board of Directors for part of this time (1925-1928). She even assisted her sister Jean Large, a professional writer, in drafting Nancy Goes Scouting, a book for young adults in the late 1920's.

While working for the national organization, Lou Hoover also simultaneously founded troops in the two cities she then called home, Washington, D.C. and Palo Alto, California. In creating Troop VII and then becoming its Troop Leader in Washington, Lou Hoover included both white and African-American girls, an extremely rare integration for young children of that generation; she had two stints in this role (1917-1918 and 1922-1928). With her dual residency in California, she did likewise in Palo Alto, helping to found the troop there in 1917. Expanding from it, she helped create the Santa Clara Council in 1922, thereby opening the movement to the western states. She served as a member of the Palo Alto Council for two separate periods (1923-1927).

Lou Hoover put into practice one of her primary contributions to the organization; organizing and training its adult troop leaders. To this end, she proposed building one of the "little houses" that could be utilized for both leadership and the girl membership as a headquarters.

She and two fellow board members of the Palo Alto branch contributed five hundred dollars each to build it, and the city donated a portion of land for its site. Local craftsman and laborers donated their skills to help build the structure. After four years from concept to completion, Lou Hoover dedicated the site in June of 1926. Located in Palo Alto's Rinconada Park, it remains the country's oldest such Girl Scout House in continuous use. She and two fellow board members of the Palo Alto branch contributed five hundred dollars each to build it, and the city donated a portion of land for its site. Local craftsman and laborers donated their skills to help build the structure. After four years from concept to completion, Lou Hoover dedicated the site in June of 1926. Located in Palo Alto's Rinconada Park, it remains the country's oldest such Girl Scout House in continuous use.

Despite her involvement in the management and business aspects of the Girl Scouts, Lou Hoover never lost her love of leading hikes, pointing out rock formations and wildlife, the practicalities of sleeping under the stars and even building fires and roasting food over it. Throughout her career in the organization, she would visit Girl Scout camps all through the United States and participated in numerous ceremonies honoring troops.

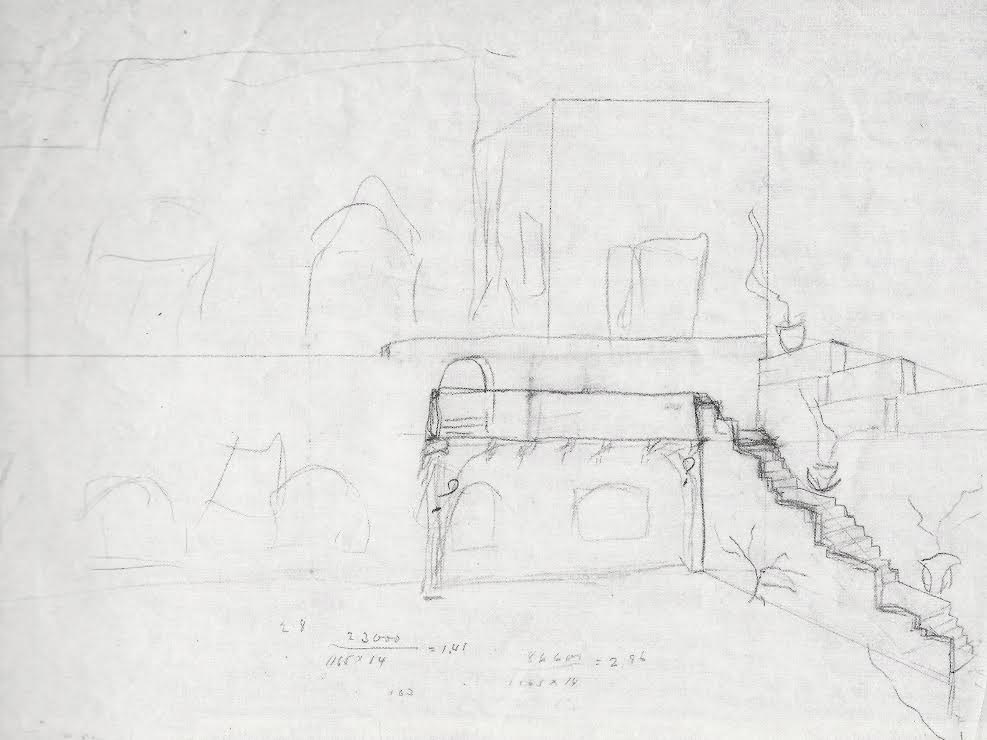

Although now in Washington, Lou and Herbert Hoover had every intention of returning to Palo Alto, California after World War I ended. Anticipating that, the couple first commissioned architect Louis Mulgardt to begin designs but when he announced it to the press in the midst of wartime deprivation, they fired him.

The couple then had Stanford University art professor Arthur B. Clark, an amateur architect, begin the project but on the condition that it was Lou Hoover's design. Her intent was clear and executed with exacting professionalism. While not a trained architect, she admitted, "I have often wished that I had time to make a profession of it." It was her vision to employ cubic blocks and terraces throughout the rambling structure. She did not want a home that could be described or identified by any known architectural style, but rather which fused the many divergent types she had seen around the world, from the square homes of Algeria to those of Native American adobes. Radically modernistic in its overall look, it remains a true reflection of Mrs. Hoover's embrace of many different world cultures, and was dubbed "International" in its look. The couple then had Stanford University art professor Arthur B. Clark, an amateur architect, begin the project but on the condition that it was Lou Hoover's design. Her intent was clear and executed with exacting professionalism. While not a trained architect, she admitted, "I have often wished that I had time to make a profession of it." It was her vision to employ cubic blocks and terraces throughout the rambling structure. She did not want a home that could be described or identified by any known architectural style, but rather which fused the many divergent types she had seen around the world, from the square homes of Algeria to those of Native American adobes. Radically modernistic in its overall look, it remains a true reflection of Mrs. Hoover's embrace of many different world cultures, and was dubbed "International" in its look.

Fireproofed, rambling, with hidden terraces and outdoor living rooms, its main entrance high on a hill gave it a look of a smaller house than it was; much of its expanse was hidden on the back side, three stories reaching down a long slop. Lou Hoover drew sketches for her vision and oversaw construction.

Finished in June of 1920, the Hoovers lived here for brief periods of time through the Twenties and early Thirties, and for a longer stretch after leaving the White House in 1933, though eventually taking a New York apartment in 1940.

The remarkably designed house was donated to the university where it serves as the president's private home. Although several First Ladies, from Lucretia Garfield to Jackie Kennedy took a direct role in determining the look of homes they had built for themselves, the Hoover home is the only example of architecture largely designed by a First Lady. The remarkably designed house was donated to the university where it serves as the president's private home. Although several First Ladies, from Lucretia Garfield to Jackie Kennedy took a direct role in determining the look of homes they had built for themselves, the Hoover home is the only example of architecture largely designed by a First Lady.

Traveling frequently across the continental United States was a delight Lou Hoover indulged in many times. In 1921, for example, she drover her own car from northern California to Washington, D.C., stopping to visit both her and her husband's birthplaces, Waterloo and West Branch, Iowa, respectively. She also made her first visit to the territory of Alaska in July of 1923, joining her husband as part of President Warren Harding's presidential junket there by ship.

Her relationship with First Lady Florence Harding was cordial, if formal, though both shared the conviction that young women should be given equal opportunities in their professional, civic and athletic lives. With the Hardings in San Francisco at the time of the President's sudden death, she interacted with the press as a buffer for Florence Harding. Her relationship with First Lady Florence Harding was cordial, if formal, though both shared the conviction that young women should be given equal opportunities in their professional, civic and athletic lives. With the Hardings in San Francisco at the time of the President's sudden death, she interacted with the press as a buffer for Florence Harding.

Disliking the time-consuming and old-fashioned custom of having to leave calling cards on formal social visits to other spouses of political figures in Washington, Lou Hoover prevailed upon her fellow Cabinet wives to agree to end the custom, thereby single-handedly ending a 19th century custom that was a burden to more civically active women of the early 20th century like herself.

At complete ease in delivering public speeches to large audiences, through the Twenties, Lou Hoover's membership and involvement in numerous women's clubs and associations had her speaking across the country on various topics. In the fall of 1923, she spoke to the Pan-American International Women's Committee, suggesting that an understanding of women leaders from different countries could be a component in furthering better international relations. At complete ease in delivering public speeches to large audiences, through the Twenties, Lou Hoover's membership and involvement in numerous women's clubs and associations had her speaking across the country on various topics. In the fall of 1923, she spoke to the Pan-American International Women's Committee, suggesting that an understanding of women leaders from different countries could be a component in furthering better international relations.

She further arranged for speakers that day to address crowds in simultaneous meetings in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Costa Rica, Haiti, Cuba, Mexico, Panama and Venezuela. Along these lines, she declared in a 1923 speech to the League of Women Voters that women were "here to stay" in the political process.

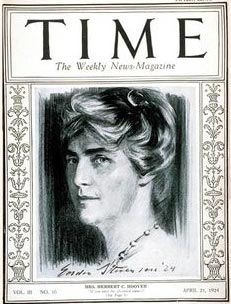

In reaction to the Harding Administration scandals involving Justice Department's Prohibition division malfeasance, Lou Hoover headed a national Women's Conference on Law Enforcement, through the General Federation of Women's Clubs on 11 April 1924. Her fair-mindedness, as well as her extraordinary degree of public service landed her on the cover of Time magazine, the first time any future First Lady was so honored.

A month later, in St. Paul, Minnesota, she addressed the National Congress of Mothers and Parent-Teachers Association. That autumn, she was host to women of some thirty-nine nations, representatives to the International Council of Women's Peace Conference. In May of 1927, in a speech to the Daughters of the American Revolution, she voiced her support for the freer, albeit more revealing, clothing of young women of the era, considering the style to be "sensible." Sometimes her work assumed a direct engagement: with her snowy-white hair, she was anticipated annually as "Mrs. Claus" at the Washington's Children Hospital. A month later, in St. Paul, Minnesota, she addressed the National Congress of Mothers and Parent-Teachers Association. That autumn, she was host to women of some thirty-nine nations, representatives to the International Council of Women's Peace Conference. In May of 1927, in a speech to the Daughters of the American Revolution, she voiced her support for the freer, albeit more revealing, clothing of young women of the era, considering the style to be "sensible." Sometimes her work assumed a direct engagement: with her snowy-white hair, she was anticipated annually as "Mrs. Claus" at the Washington's Children Hospital.

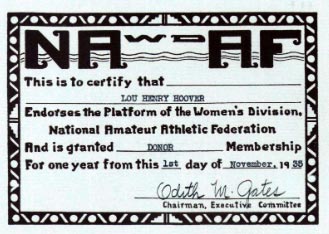

Besides her work with the Girl Scouts, and among her dozens of commitments to public service organizations, Lou Hoover was also a key figure in the era's movement to widen opportunity for women in athletic activities. Besides her work with the Girl Scouts, and among her dozens of commitments to public service organizations, Lou Hoover was also a key figure in the era's movement to widen opportunity for women in athletic activities.

In 1922 she was named as the only woman on the board as a vice president of the National Amateur Athletic Association. As the popular culture of the era increasingly depicted the physical liberation of women from everything ranging from constricted clothing to household labor chores, resulting from shorter and lighter fashions and technology in the home; an increased public interest in women's health coincided with a growing national obsession with sporting events.

Still, the idea of young girls moving their bodies immodestly and vigorously as men shocked traditionalists. Lou Hoover had joined the association board, with the intention of expanding to women its message of the physical and mental value of athletics.

A year after she joined the board, she helped for found and served as President of its Women's Division (1923-1940). Among the issues she sought to address were the arguments against women joining in sporting competitions such as the Olympics, and the need for more sports facilities, trainers and coaches for women. In April of 1923 she opened a conference on the issue that concluded with the plan to encourage a sense of equality among women and their participation in sports that were "healthful." A year after she joined the board, she helped for found and served as President of its Women's Division (1923-1940). Among the issues she sought to address were the arguments against women joining in sporting competitions such as the Olympics, and the need for more sports facilities, trainers and coaches for women. In April of 1923 she opened a conference on the issue that concluded with the plan to encourage a sense of equality among women and their participation in sports that were "healthful."

While a successful fundraiser for the organization, she found resistance to long-term corporate underwriting. Ultimately, she helped craft the organization's mission in the "promotion of competition that stresses enjoyment of sport and the development of good sportsmanship and character rather than those types that emphasize the making and breaking of records, and the winning of championships for the enjoyment of spectators and for the athletic reputation or commercial advantages of institutions and organizations." Eventually, it merged into the American Association for Health, Physical Education, and Recreation.

Campaign and Inauguration:

Despite her experience as a professional speaker to large audiences who addressed public issues, Lou Hoover assumed no such public role in her husband's 1928 and 1932 presidential campaigns and was not known to exercise any especial degree of influence over how the campaign was conducted or the tone of her husband's campaign. Despite her experience as a professional speaker to large audiences who addressed public issues, Lou Hoover assumed no such public role in her husband's 1928 and 1932 presidential campaigns and was not known to exercise any especial degree of influence over how the campaign was conducted or the tone of her husband's campaign.

Even when some of her husband's more underhanded supporters attacked the Catholic faith of his opponent, Democratic New York Governor Al Smith, and even the heavyset appearance and working-class origins of his wife, Lou Hoover remained uncharacteristically mute in reaction. She was utterly unfamiliar with the unpredictable nature of elective politics and the press coverage of a national campaign, her husband never having run for any political office before, and strived to conduct herself in a way that offered no distraction. Even when some of her husband's more underhanded supporters attacked the Catholic faith of his opponent, Democratic New York Governor Al Smith, and even the heavyset appearance and working-class origins of his wife, Lou Hoover remained uncharacteristically mute in reaction. She was utterly unfamiliar with the unpredictable nature of elective politics and the press coverage of a national campaign, her husband never having run for any political office before, and strived to conduct herself in a way that offered no distraction.

She joined him in a post-election, pre-inauguration "Good Neighbor" trip to Honduras, San Salvador, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Chile, Peru, Argentina, Latin America.

Immediately preceding the 1929 swearing-in ceremony of her husband as President in the U.S. Capitol Building, Lou Hoover and the outgoing First Lady Grace Coolidge were not escorted and lost their way in the labyrinth of hallways that led to the West Front, where the ceremonies were to take place; their delay inadvertently delayed the ceremony. Immediately preceding the 1929 swearing-in ceremony of her husband as President in the U.S. Capitol Building, Lou Hoover and the outgoing First Lady Grace Coolidge were not escorted and lost their way in the labyrinth of hallways that led to the West Front, where the ceremonies were to take place; their delay inadvertently delayed the ceremony.

Following the tradition since the 1913 Inauguration of Woodrow Wilson, there was no Inaugural Ball.

First Lady:

54 years old

4 March 1929 – 4 March 1933

Establishing Parameters:

Despite her enormous record of activism, public speaking, fundraising, and acute degree of conscientious professionalism in all that she did, upon becoming First Lady Lou Hoover decided to restrict the degree of what had been an adult life of public activism. She did this on the premise that she would be expected to behave publicly in a way that did not defy the feminine traditional decorum associated with her new status. Seemingly overnight, her words and deeds assumed a previously unseen subdued nature.

Unquestionably the single greatest incident that influenced her to maintain her initially cautious approach was the massive failure on Wall Street that occurred just six months into the Hoover Administration. The full measure of the Great Depression's impact did not immediately affect the nation as a whole; rather, it unfolded over time with every hope that the economy would correct itself. With each ensuing month, however, came greater unemployment and eventually loss of income and home. Behaving in a way that might strike the public as aberrant rather than serve to provide a steadying perception became a guiding principal for her as she made decisions of what to do or not do as First Lady. Unquestionably the single greatest incident that influenced her to maintain her initially cautious approach was the massive failure on Wall Street that occurred just six months into the Hoover Administration. The full measure of the Great Depression's impact did not immediately affect the nation as a whole; rather, it unfolded over time with every hope that the economy would correct itself. With each ensuing month, however, came greater unemployment and eventually loss of income and home. Behaving in a way that might strike the public as aberrant rather than serve to provide a steadying perception became a guiding principal for her as she made decisions of what to do or not do as First Lady.

Within these parameters, however, she initiated numerous innovations that truly helped to modernize the public role of a First Lady and extended it more overtly into the public realm than it had ever previously been.

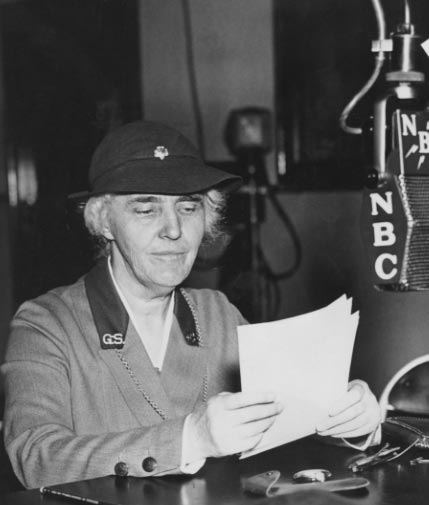

Radio Speeches:

Nevertheless, she made one immediate innovation that set a precedent which her successors followed or were criticized for not doing: she continued to deliver speeches not only in auditoriums but to also give public addresses over the radio. Just over a month after becoming First Lady, her brief 19 April 1929 speech to the Daughters of the American Revolution was carried on the radio. Nevertheless, she made one immediate innovation that set a precedent which her successors followed or were criticized for not doing: she continued to deliver speeches not only in auditoriums but to also give public addresses over the radio. Just over a month after becoming First Lady, her brief 19 April 1929 speech to the Daughters of the American Revolution was carried on the radio.

Others soon followed: 22 June 1929 to the 4-H Clubs; 23 March 1931 as a representative of the Women's Division of the President's Emergency Committee for Employment; 6 May 1931 to the New York Maternity Center Association – along with former First Lady Edith Roosevelt making her first public remarks to be recorded – on the subject of infant and new-mother mortality in America; 7 November 1931, again to the 4-H Clubs; 27 November 1932 on behalf of the National Women's Committee of the Welfare and Relief Mobilization of 1932, on the topic of "The Woman's Place in the Present Emergency".

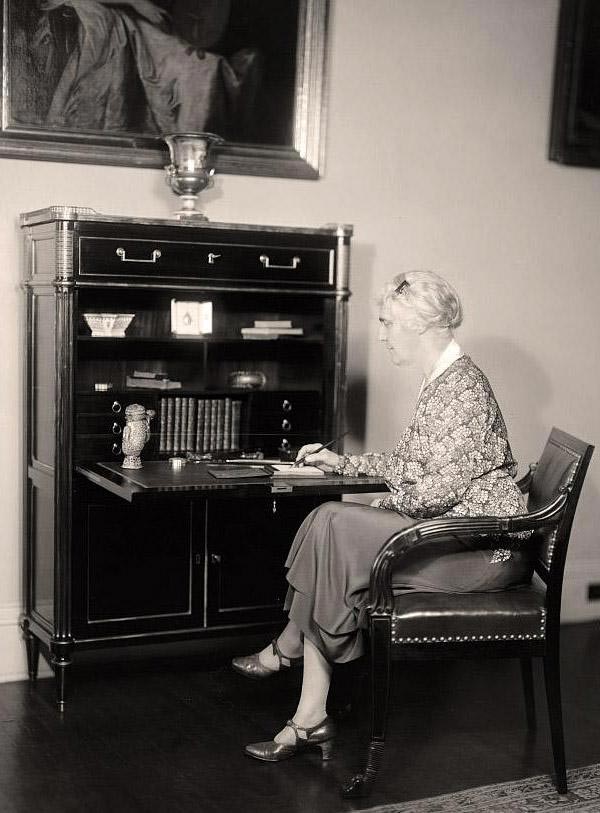

Mrs. Hoover took her "talkie voice" seriously enough that she had a recording system set up in the White House enabling her to replay her recordings and test the pitch, tone and pacing of her voice. With a great interest in the popular films of her era, Lou Hoover had equipment placed in the oval room of the family quarters to screen sound motion pictures for her guests, the equipment and installation donated by a Hollywood studio.

With a particular fascination for science and technology, Lou Hoover had none of the hesitation towards using new media as did many other women of her status and class at the time. There was no sense that she was compromising her dignity, for example, by having her voice recorded. She also used her own silent movie camera in her private life.

Apart from keeping abreast of new media and the progression of the economic downturn, Lou Hoover maintained a curiosity of the popular culture. She came to know many of the celebrities of the era, from Amelia Earhart to orchestra band singer and actor Rudy Vallee. On another, more tragic aspect of her era's popular culture, the 1932 kidnapping of aviator Charles Lindbergh's baby son, Lou Hoover kept in close touch with the child's mother, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, a personal friend. Apart from keeping abreast of new media and the progression of the economic downturn, Lou Hoover maintained a curiosity of the popular culture. She came to know many of the celebrities of the era, from Amelia Earhart to orchestra band singer and actor Rudy Vallee. On another, more tragic aspect of her era's popular culture, the 1932 kidnapping of aviator Charles Lindbergh's baby son, Lou Hoover kept in close touch with the child's mother, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, a personal friend.

Mrs. Hoover greeting the popular bandleader and crooner of the era, Rudy Vallee. (Washington Evening Star)

Relationship with Press:

Unfortunately, Lou Hoover's radio addresses were the extent of her use of the modern media. Following a traditional tact of First Ladies, she refused to grant any formal interviews to print or broadcast journalists during her tenure, though she would answer to impromptu questions that reporters might be able to pose to her. Despite her long life in the public eye, she had a growing mistrust of the media, especially as the Great Depression worsened and she read accounts involving the President that she felt had been distorted and thus failed to serve the public with truth.

Her interactions with the overwhelmingly female members of the national press corps that regularly covered the social and family life of Presidents was always polite but decidedly distant. Bess Furman of the New York Times later recalled that the only way she was able to report an eyewitness account of Christmas during the Hoover years was to dress as an older Girl Scout and join members of the group that had been invited by Mrs. Hoover to lead in a holiday music interlude. In time, Bess Furman became the only reporter covering the White House who earned the First Lady's trust. Her interactions with the overwhelmingly female members of the national press corps that regularly covered the social and family life of Presidents was always polite but decidedly distant. Bess Furman of the New York Times later recalled that the only way she was able to report an eyewitness account of Christmas during the Hoover years was to dress as an older Girl Scout and join members of the group that had been invited by Mrs. Hoover to lead in a holiday music interlude. In time, Bess Furman became the only reporter covering the White House who earned the First Lady's trust.

While she was uncomfortable exposing herself to the questions of print reporters, knowing she often felt compelled to politely respond to, rather than ignore them, Lou Hoover was entirely at ease in front of movie newsreel cameras, speaking a few words with poise and command. While she was uncomfortable exposing herself to the questions of print reporters, knowing she often felt compelled to politely respond to, rather than ignore them, Lou Hoover was entirely at ease in front of movie newsreel cameras, speaking a few words with poise and command.

With her fascination for new technologies, she also owned and operated not just her own still picture cameras but home movie camera.

White House History:

Lou Hoover furbished the private West Sitting Hall of the second floor, the large central area of the family quarters, in what was called a "California style," with palm trees and other tropical plants, birds singing in hanging cages and outdoor grass carpeting. For her three small grandchildren, who lived with the Hoovers in the White House for several months in 1929 and 1930, she had a fireproof playroom furnished.

She also took an avid interest in the historical character of the old mansion and made several important changes to help institutionalize this: in 1929, she and the President gathered furniture known to have existed or been used by Abraham Lincoln in a guest room that was used as a "Lincoln Study." It was the genesis for later President Harry Truman's creating the legendary "Lincoln Bedroom". She also took an avid interest in the historical character of the old mansion and made several important changes to help institutionalize this: in 1929, she and the President gathered furniture known to have existed or been used by Abraham Lincoln in a guest room that was used as a "Lincoln Study." It was the genesis for later President Harry Truman's creating the legendary "Lincoln Bedroom".

Similarly, she sought items used by President James Monroe and his wife and also commissioned exact replicas of other items they had used, gathering them into another upstairs room and thus christened the shorter-lived "Monroe Room" (to be known in the late 20th century as the "Treaty Room" and then the "President's Study").

In the public state rooms, Lou Hoover paired the full-length portraits of George and Martha Washington together in the East Room, a placement which has remained since then. Simultaneous to this search for historic items, she commissioned in 1930 one of her aides and collaborated on what would prove to be the first comprehensive inventory and cataloguing of the White House collection of historic objects. Rather than seek funding public funding, she personally paid for all these projects. In the public state rooms, Lou Hoover paired the full-length portraits of George and Martha Washington together in the East Room, a placement which has remained since then. Simultaneous to this search for historic items, she commissioned in 1930 one of her aides and collaborated on what would prove to be the first comprehensive inventory and cataloguing of the White House collection of historic objects. Rather than seek funding public funding, she personally paid for all these projects.

Developing the first Presidential Retreat:

Recognizing the need for the President to escape for regular breaks from the oppressive heat and work atmosphere of the city, Lou Hoover found and purchased 164 acres of wooded property on the Rapidan River in Virginia, set in the Blue Ridge Mountain range. Recognizing the need for the President to escape for regular breaks from the oppressive heat and work atmosphere of the city, Lou Hoover found and purchased 164 acres of wooded property on the Rapidan River in Virginia, set in the Blue Ridge Mountain range.

Beginning in the spring of 1929, she began architectural and landscape renderings to create a presidential retreat there, a series of small log cabins for guests, and a larger central with a stone fireplace. Bridges, pathways and even trout pools were created. Here the Hoovers spent most weekends, often entertaining guests. Lou Hoover also hosted Girl Scout events here.

At the end of the Administration, the Hoovers donated the entire property and buildings to the federal government. Camp Rapidan, still used as a federal retreat, is opened to the public. At the end of the Administration, the Hoovers donated the entire property and buildings to the federal government. Camp Rapidan, still used as a federal retreat, is opened to the public.

Appalachian School:

In August 1929, just shortly after they began using Camp Rapidan, Herbert and Lou Hoover discovered that there was a community of impoverished Appalachian families nearby, with no tax base to provide a school for their children. The couple decided to establish a school for the local mountain children, as well as a small residence for the teacher they hired to instruct them, Christine Vest of Berea College. Opened on 24 February 1930, it came to be known as "The President's Community School." In August 1929, just shortly after they began using Camp Rapidan, Herbert and Lou Hoover discovered that there was a community of impoverished Appalachian families nearby, with no tax base to provide a school for their children. The couple decided to establish a school for the local mountain children, as well as a small residence for the teacher they hired to instruct them, Christine Vest of Berea College. Opened on 24 February 1930, it came to be known as "The President's Community School."

Continuing Girl Scout Leadership:

While she was First Lady, Lou Hoover did not feel it was appropriate for her to continue her formal affiliation with the Girl Scouts but rather, in the tradition she herself had initiated with Edith Wilson, served as its Honorary President, from 1929 to 1933. Even in this capacity, however, she still had an important impact, supporting the restructuring of the entire organization with a standardization that nevertheless allowed for the unique needs of different national regions.

In her first as First Lady, Lou Hoover raised more than $500,000 toward reaching a five-year development plan in expanding the organizational structure as the Girl Scouts rapidly expanded across the country. She also attended and addressed its annual conventions in New Orleans, Indianapolis, Buffalo, and Virginia Beach, during her tenure as First Lady. Lou Hoover also proofread the various handbooks that the Girl Scouts issued for its membership, whether they be guides to exploring and identifying natural life or instructional manuals on baking. In September of 1931, she hosted the annual meeting of the executive board at Camp Rapidan. In her first as First Lady, Lou Hoover raised more than $500,000 toward reaching a five-year development plan in expanding the organizational structure as the Girl Scouts rapidly expanded across the country. She also attended and addressed its annual conventions in New Orleans, Indianapolis, Buffalo, and Virginia Beach, during her tenure as First Lady. Lou Hoover also proofread the various handbooks that the Girl Scouts issued for its membership, whether they be guides to exploring and identifying natural life or instructional manuals on baking. In September of 1931, she hosted the annual meeting of the executive board at Camp Rapidan.

Women's Equality:

As First Lady, Lou Hoover continued her belief in the equality of women and men. In her 1929 remarks to the 4-H Club broadcast on NBC, for example, she emphasized that housework was for men too, and that boys should learn to clean the house and wash the dishes along with the girls, because they were " "just as great factors in the home-making of the family as are the girls."

In numerous ways, Lou Hoover broke from social restrictions long placed around women. Among friends and family, in the privacy of Camp Rapidan, she sported riding pants without worry of judgment. She broke the unwritten code that pregnant women who were beginning to physically appear so, should cease to be seen in public, and encouraged expectant mothers to attend her White House events, even inviting women in this condition to receive guests with her. When a pregnant White House servant assumed the First Lady would not want her working there, Lou Hoover reacted by insisting she use the elevators instead of climbing stairs and work less hours if she needed to. Using the family elevator was a privilege that Lou Hoover also extended to a disabled servant. In numerous ways, Lou Hoover broke from social restrictions long placed around women. Among friends and family, in the privacy of Camp Rapidan, she sported riding pants without worry of judgment. She broke the unwritten code that pregnant women who were beginning to physically appear so, should cease to be seen in public, and encouraged expectant mothers to attend her White House events, even inviting women in this condition to receive guests with her. When a pregnant White House servant assumed the First Lady would not want her working there, Lou Hoover reacted by insisting she use the elevators instead of climbing stairs and work less hours if she needed to. Using the family elevator was a privilege that Lou Hoover also extended to a disabled servant.

Some historians have suggested that Lou Hoover may have influenced Herbert Hoover's December 1932 Executive Order 5984. This order enlarged the Civil Service Rule VII to now permit job nominations "without regard to sex," unless the type of work of a federal job required specific tasks that only one of the genders could perform (such as guard of a federal women's prison or extreme physical strength). While no documentation suggests that she specifically lobbied for this action, its intent is wholly compatible with her views on gender equality; certainly after a lifetime of exchanging their well-informed opinions with each other in the privacy of their home, it is certain that the order would have had her complete support.

Vigorous in her belief that education would be the key to long-term and permanent success of women, Lou Hoover paid entirely for the higher education of a number of women. She received a number of honorary degrees as First Lady – far more than any of her predecessors: Swathmore College (1929), Elmira College (1930), Goucher College (1931), Tufts College (1932), Wooster College (1932). She had also received honorary degrees before and after her tenure as First Lady: Mills College (1923), Whittier College (1928), and Stanford University (1941). In addition, several schools were named for her, ranging from Lou Henry Hoover Elementary School in Whittier, California (1938) to Lou Henry Elementary School, in Waterloo, Iowa (2005). Among the San Jose State University dormitories is one named "Hoover Hall" in her honor. Vigorous in her belief that education would be the key to long-term and permanent success of women, Lou Hoover paid entirely for the higher education of a number of women. She received a number of honorary degrees as First Lady – far more than any of her predecessors: Swathmore College (1929), Elmira College (1930), Goucher College (1931), Tufts College (1932), Wooster College (1932). She had also received honorary degrees before and after her tenure as First Lady: Mills College (1923), Whittier College (1928), and Stanford University (1941). In addition, several schools were named for her, ranging from Lou Henry Hoover Elementary School in Whittier, California (1938) to Lou Henry Elementary School, in Waterloo, Iowa (2005). Among the San Jose State University dormitories is one named "Hoover Hall" in her honor.

Personal Life:

Lou Hoover's personal lifestyle was far less restricted than many of her predecessors. She continued to drive herself in her own car around Washington, and could often be seen walking along the long greensward of the area of monuments to the south of the White House and along the streets of the city. She worked in the flower gardens of the mansion, and walked her Elkhound and German shepherd dogs on the property. Lou Hoover's personal lifestyle was far less restricted than many of her predecessors. She continued to drive herself in her own car around Washington, and could often be seen walking along the long greensward of the area of monuments to the south of the White House and along the streets of the city. She worked in the flower gardens of the mansion, and walked her Elkhound and German shepherd dogs on the property.

The First Lady also found joy in riding her horse in nearby Rock Creek Park, where she was also known to bring a food basket and blanket for a picnic with friends. Despite such informality, she had an intensely strong resistance to verbally expressing her thoughts and feelings and it often led servants and others to express a feeling of arrogance or aloofness to her. Most galling to some servants was her silent use of various hand signals to indicate her orders. The First Lady also found joy in riding her horse in nearby Rock Creek Park, where she was also known to bring a food basket and blanket for a picnic with friends. Despite such informality, she had an intensely strong resistance to verbally expressing her thoughts and feelings and it often led servants and others to express a feeling of arrogance or aloofness to her. Most galling to some servants was her silent use of various hand signals to indicate her orders.

Lou Hoover sought to ensure the highest quality of service and hospitality to her guests, including the avoidance of any potential conflicts among them. When the sister and hostess of the widower Vice President, Dolly Gann, let it be known that she expected the same protocol rank that would be automatically given to a vice presidential spouse, the wife of the Speaker of the House, Alice Roosevelt Longworth, went on the record stating this was wrong and that her husband's position afforded her a higher ranking that Dolly Gann.

To avoid taking sides on the issue, Lou Hoover simply added an extra official dinner to honor the Vice President in a White House social schedule that already included such dinners for the Speaker of the House (at which members of the House were guests), Chief Justice (at which the other justices were invited as well), the Cabinet (all the members of whom were invited) and Diplomatic Corps. While the press perceived it as a tactic that only avoided answering the issue, Lou Hoover claimed it was an innovation to honor a branch of the legislature that had been ignored – the Senate, of which the Vice President serves as president. Indeed, the event remained on White House entertaining schedules in succeeding Administrations and the entire U.S. Senate membership was finally included in the dinners.

The DePriest Controversy & Confronting Racism:

Lou Hoover used a similar approach when she had to host her first season of teas for Congressional spouses in the spring of 1929 – however, it was a delicate situation fraught with the ugly perspective of racial segregation and bigotry.

Among the spouses to be invited that year was Jessie DePriest, the wife of freshman Chicago Congressman, both of whom were African-American. As far as her own personal views, Lou Hoover was a staunch egalitarian with a genuine belief in the utter correctness of social interaction between people of all races. Although her own circle of close friends was of the same racial and socioeconomic background as herself, she herself had traveled the world and interacted with people from completely different origins than her own. She never had any hesitation about inviting Jessie DePriest, only how to handle those white segregationists who might balk or treat their fellow spouse congressional spouse poorly. Among the spouses to be invited that year was Jessie DePriest, the wife of freshman Chicago Congressman, both of whom were African-American. As far as her own personal views, Lou Hoover was a staunch egalitarian with a genuine belief in the utter correctness of social interaction between people of all races. Although her own circle of close friends was of the same racial and socioeconomic background as herself, she herself had traveled the world and interacted with people from completely different origins than her own. She never had any hesitation about inviting Jessie DePriest, only how to handle those white segregationists who might balk or treat their fellow spouse congressional spouse poorly.

It was further complicated by a political reality: a large percentage of Democrats from the southern states who had rigorously upheld segregation laws, had abandoned their party in 1932 to support the Republican Hoover for President. Lou Hoover decided to hold five separate teas. Inviting Jessie DePriest to one of the first of these might well have provoked a boycott of the remaining teas and so Lou Hoover invited her to the final tea on 12 June 1929.

Among the other congressional wives in attendance, each had been sounded out to ensure their support of the social integration; Lou Hoover also widened the list to include her supportive women staff, her sister and several other officials and spouses, including the State Department's Chief of Protocol – an important symbol signaling the rightness of the invitation. Lou Hoover made it clear to the White House guards that they were to permit the African-American woman into the mansion and made it a point to be seen shaking the hand of Jessie DePriest. Among the other congressional wives in attendance, each had been sounded out to ensure their support of the social integration; Lou Hoover also widened the list to include her supportive women staff, her sister and several other officials and spouses, including the State Department's Chief of Protocol – an important symbol signaling the rightness of the invitation. Lou Hoover made it clear to the White House guards that they were to permit the African-American woman into the mansion and made it a point to be seen shaking the hand of Jessie DePriest.

As the First Lady feared, the outraged reaction of segregationists was immediate and harsh. Southern newspaper editorials (Houston Chronicle, Austin Times, Montgomery [Alabama] Advertiser, Memphis Commercial Appeal, and Jackson [Mississippi] Daily News) accused her of "degradation" and "defiling" the White House by breaking a societal taboo. Three state legislatures took up a formal vote to censure the First Lady – Texas, Florida and Georgia. On 18 June 1929, U.S. Senator Thaddeus H. Caraway of Arkansas had an account of the event read into the Congressional record. Southern Congressman declared that they had "bow[ed] our heads in shame and regret" over the First Lady's action.

Soon a flood of vicious letters and telegrams poured down on Lou Hoover. Despite her foreknowledge of their tone, she insisted on reading some of them herself. While fearing any negative affect she may have provoked on the President, her published biographies have also ignored the pained sadness she experienced in facing the attitudes of a segment of her fellow citizens. Her own exposure to non-white Americans was limited to those of the educated and elite class whom she treated with the same respect and equality as white people of that class. Largely, however, her interaction with non-whites was from the perspective of an employer of servants and here she at times made mild but condescending observations related to their racial backgrounds. Soon a flood of vicious letters and telegrams poured down on Lou Hoover. Despite her foreknowledge of their tone, she insisted on reading some of them herself. While fearing any negative affect she may have provoked on the President, her published biographies have also ignored the pained sadness she experienced in facing the attitudes of a segment of her fellow citizens. Her own exposure to non-white Americans was limited to those of the educated and elite class whom she treated with the same respect and equality as white people of that class. Largely, however, her interaction with non-whites was from the perspective of an employer of servants and here she at times made mild but condescending observations related to their racial backgrounds.

Lou Hoover treated racism with neglect; she did not publicly speak out and simply reacted as if it did not exist with the apparent intention that one should rise above such thinking, remarks and behavior. Certainly by living and travelling for many years in non-European nations, she had become far more exposed to different cultures than any of her predecessors had been at the time they assumed the First Lady position. In 1921, upon her settlement back in the United States, when she had finalized the purchase of their Washington home, Lou Hoover refused to sign a legal agreement that would forbid the Hoovers from later selling the property to African-Americans or Jews.

Mrs. Hoover applied her belief in the value of pursuing higher education as the greatest method for overcoming limitations placed on any person to a White House maid by committing to underwrite the woman of color's college education. Just weeks before becoming First Lady, while traveling in the South with an African-American couple who worked for her yet with whom she enjoyed sharing experiences, Lou Hoover suggested they all do some sightseeing together. She was either naïve to the reality that African-Americans would not be permitted to go into some places with her, or simply refused to acknowledge segregation the respect of abiding by it.

While her reason can only be speculative, Lou Hoover was also well-informed person who also had the ability to remain mute about certain issues. Following the DePriest incident, Lou Hoover made no public apology for, or clarification of her decision. The very next week, her husband welcomed the African-American president of the Tuskegee Institute to lunch in the White House, a mute but decisive if symbolic gesture indicating support for his wife.

Lou Hoover also seemed to have an expressed interest in Native American culture. Following a diplomatic corps dinner on 11 February 1933, Lou Hoover invited the Yakima tribe's Chief Yowlache to perform at a post-dinner concert that also included a traditional opera singer and harpist. Appearing in the colorful full tribal costume of his tribe, Yowlache demonstrated Zuni Indian tribal chants – as well as Italian operatic arias. In her post-White House years, Lou Hoover also voiced her strong desire to enlist more Native-Americans in the Girl Scouts. Lou Hoover also seemed to have an expressed interest in Native American culture. Following a diplomatic corps dinner on 11 February 1933, Lou Hoover invited the Yakima tribe's Chief Yowlache to perform at a post-dinner concert that also included a traditional opera singer and harpist. Appearing in the colorful full tribal costume of his tribe, Yowlache demonstrated Zuni Indian tribal chants – as well as Italian operatic arias. In her post-White House years, Lou Hoover also voiced her strong desire to enlist more Native-Americans in the Girl Scouts.

The Great Depression:

No single event more defined and overshadowed the Hoover Administration than the dramatic drop of the stock market in October of 1929. Beginning what would soon be known as the Great Depression, it was a time of unprecedented loss of stock market investments, business failures, factory closings, housing losses, and mass unemployment. As it worsened over the course of the Hoover Administration, the lack of earnings began t hit American families of all classes; those without substantial cash savings or the prospects of employment were often unable to afford the most basic needs of food, shelter and clothing.

In light of Herbert Hoover's enormously successful relief programs during World War I, Lou Hoover had confidence in and supported her husband's policy to meet the crisis not through any federal government intervention but rather small- and large-scale volunteer drives to alleviate either widespread suffering or individual cases.

Lou Hoover attempted to put this philosophy into practice. As the economic crisis worsened into 1930 and 1931, she began to receive hundreds and then thousands of letters from citizens appealing for particular types of help – money, food, employment, clothing – she took it upon herself to respond personally. She would refer the request for support to a wealthy friend or organization such as the Red Cross, Community Chest, Salvation Army and American Friends Service Committee - or, most astoundingly, send a personal "loan" to the stranger.

As more requests poured in, the First Lady hired an aide to handle and process them. Despite the Hoovers' publicly-stated belief that federal government intervention in the crisis was wrong, Lou Hoover had the requests for aid that she received first reviewed to see if it was a situation that could be alleviated by those federal programs which were established and remained intact. She herself paid the salaries of her three secretaries, while her Social Secretary was, as had been true of her predecessors, the single federally-salaried member of her staff. As more requests poured in, the First Lady hired an aide to handle and process them. Despite the Hoovers' publicly-stated belief that federal government intervention in the crisis was wrong, Lou Hoover had the requests for aid that she received first reviewed to see if it was a situation that could be alleviated by those federal programs which were established and remained intact. She herself paid the salaries of her three secretaries, while her Social Secretary was, as had been true of her predecessors, the single federally-salaried member of her staff.

Another solution she provided came, in the context of her role as hostess. Helping arrange and publicize a series of five concerts by famed Polish pianist Ignace Jan Paderewski to benefit American Red Cross relief efforts, she hosted the Washington event in the White House on 25 January 1932; others took place in New York, Boston, Philadelphia and Chicago. Nearly $12,000 was raised, the First Lady also making a personal donation. Another solution she provided came, in the context of her role as hostess. Helping arrange and publicize a series of five concerts by famed Polish pianist Ignace Jan Paderewski to benefit American Red Cross relief efforts, she hosted the Washington event in the White House on 25 January 1932; others took place in New York, Boston, Philadelphia and Chicago. Nearly $12,000 was raised, the First Lady also making a personal donation.

Lou Hoover made one public appearance that sought to illustrate the viability of the Hoover Administration's 1930 creation of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, a federal program providing loans to banks, insurers, and large transportation and commerce industries such as railroads and shipbuilding. In July 1930, she went to Camden, New Jersey to christen the Excalibur, a newly-built 7,000-ton cargo-passenger ship, intended as an immediate symbol of the returning economic strength through Hoover's RFC. However, Lou Hoover kept her remarks to those traditionally made at such ceremonies, leaving it to other speakers to spell out the link between the event and the RFC.

The greatest effort made by Lou Hoover to forge a modest response to the overwhelming needs generated by the Great Depression was to organize and inspire a volunteer network among the quarter of a million Girl Scout members. In 1931, she proposed this to the Girl Scout leadership and it was subsequently presented at their annual convention. In two of her radio speeches, she sought to inspire Girl Scouts to go into their communities and discover which families were struggling and then help to "plan that the excess in your community may be systematically gathered together and through the aid of the many channels of relief may be sent where it is needed." She furthered the idea that the results of the Depression could be met by volunteering for charitable organizations in her last radio address, in November of 1932, "The Woman's Place in the Present Emergency." The greatest effort made by Lou Hoover to forge a modest response to the overwhelming needs generated by the Great Depression was to organize and inspire a volunteer network among the quarter of a million Girl Scout members. In 1931, she proposed this to the Girl Scout leadership and it was subsequently presented at their annual convention. In two of her radio speeches, she sought to inspire Girl Scouts to go into their communities and discover which families were struggling and then help to "plan that the excess in your community may be systematically gathered together and through the aid of the many channels of relief may be sent where it is needed." She furthered the idea that the results of the Depression could be met by volunteering for charitable organizations in her last radio address, in November of 1932, "The Woman's Place in the Present Emergency."